Cosme Cordova, Artist and Community Arts Organizer

Cosme Cordova was born in San Pedro de la Cueva in Sonora, Mexico, and brought to Riverside, California at five years old, where he still resides. Cordova is the owner of Division 9 Gallery (Riverside, California). In 2002 he co-founded Riverside’s Arts Walk along with Mark Schooley (Riverside Community Arts Association), which has run monthly art shows in Downtown Riverside since its inception.

His artwork has been exhibited throughout California, Arizona, and Mexico. Some of those galleries include Galleria Rustica and Bunny Gunner Gallery in Pomoma, CA; Dennis Rogue Gallery in Palm Desert, CA; Rockrose Gallery in Los Angeles, and the Riverside Community Arts Association, Riverside Art Museum, Sweeney Art Gallery, Riverside Metropolitan Museum, and others in Riverside, CA. Cordova has also curated many art shows and hosted citywide art events such as the annual Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) Celebration, which attracts thousands of people, and Artnival, an art themed carnival produced by Cordova and local artists.

Cordova has been honored as the City of Riverside’s Artist of Month.

Lunch Ticket’s Art Editor Kiandra Jimenez interviewed Cordova at Division 9 Gallery in April, 2014.

Kiandra Jimenez: You are an artist who is deeply involved in the arts community in your town of Riverside, CA. You founded the Riverside Art Walk, and you run a gallery, Division 9 Gallery (D9G). What motivated you to spend all that effort on behalf of your community, versus having a solo studio practice and focusing strictly on your own creative work?

Cosme Cordova: In the beginning I didn’t really think about it too much, I just went ahead and did it. I was showing in different places: Pomona, Los Angeles, Palm Desert. I found myself traveling far and wondering why the same type of galleries or venues didn’t exist in Riverside for our artists. When I first started there was Back to the Grind [a local coffee house], and I would show there, but Riverside didn’t really have many galleries or other institutions that embraced local artists. So, I said let’s figure out a way that we can create a Riverside arts community.

Coming from a low-income community I only lived three miles from downtown, but I never came to downtown. I was in my little neighborhood, the group of people that I hung out with and was raised with. But when I started attending Riverside Community College (RCC) I was introduced to downtown. When I eventually did make it to the institutions that did showcase artists, I didn’t feel really welcomed. I didn’t feel a warm feeling. That is another reason why I decided to do something for myself—to represent the people I was raised with, and present different cultural images from artists that had different points of view about life.

Now that I’m older I look back; I was 30 then, now I am 42. I felt there was nothing for me and I wanted to do something for myself. I was angry, so I used that anger as a vehicle to open doors for myself. When I was younger I would be upset that there weren’t venues, but as I got older I realized that was my vehicle, my tool to open my own doors and create my own venues, and share my own imagery. I wanted to make sure that it didn’t matter how poor, how rich, how educated or uneducated you were as an artist. The artwork had to be unique, your own image, not a representation of other artists who are well known.

Artists come in and show me their portfolios and they look like Dalí’s, Picasso’s, or Pollock’s artwork. That’s fine, but I want to make sure that I represent artwork that represents them and you can see their own identity on the paper or canvas.

KJ: Do you have some advice/jewels of wisdom for those of us who want to devote some aspect of our creative careers to service? How do you balance your creative work with your involvement with community?

CC: We all have something that makes us tick; we all have something that makes us go forward. When we wake up we look forward to doing that one thing. Whatever that one thing is, you need to invest your time in doing it. What I mean is you have to be dedicated to something you love.

Unfortunately, nowadays we all need to have a job, but there are plenty of jobs in the art world, you just have to find something that coincides with your world.

KJ: So how do you balance your creative work with your involvement with the community, your gallery work? Would you see yourself as the artist with his brushes in the trunk, who’s driving and putting all his focus in his community and gallery work, or do you take time to pull over and paint every few miles?

I’ve been trying to get myself more organized so I have more time to create. I feel like I’m a slingshot. My energy to create pushes the rock back, I’m always stretching it as far as I can. It’s stretching, stretching, but while I’m doing that I’m actually creating ideas or concepts in my head; I’m constantly thinking of ideas I want to create. Eventually, I have free time and I create twenty, thirty images.

I think I’m blessed because I’m doing things that I love to do. I put events together, I organize events, I do my artwork, I do graphic arts for people, from business cards to logos to brochures. I get to install artwork. I get to meet people.

KJ: Let’s switch focus and discuss your own art practice. Describe your work and the ideas behind it—specifically what are you trying to communicate?

CC: The basis of my work all comes down to where I was born. I was born in Mexico and brought at the age of five to the United States. So, my perspective on United States and Mexico is interesting because it is not a normal point of view. My parents came from a very poor town. When we left, I believe there was only one TV and one telephone in a town of two thousand. Dirt floors, we were born on dirt floors to give you an idea.

So coming from a very poor background and coming to United States is like the experience of normal people here going to Disneyland. I always tell people, United States is like Disneyland. The streets are clean, the grass is clean, there is violence, but it isn’t as violent as other places, things do change if enough people get behind something, whereas in Mexico and other countries they don’t. You almost have to have a revolution for things to change.

So my artwork is always based on that perspective of making sure I don’t forget where I come from and the world that I live in, which is the United States, is Disneyland.

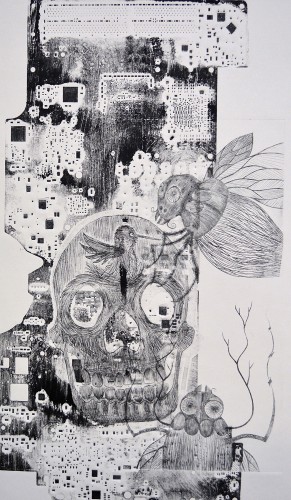

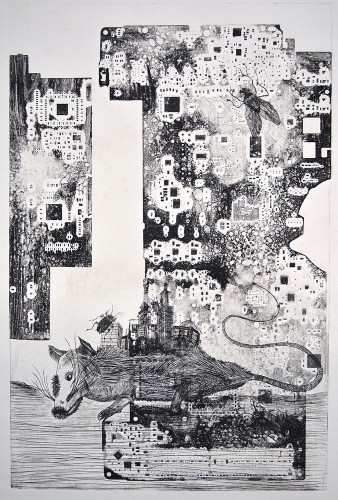

The recent work I did was pronto plates, etchings, and monotype, a combination of the three. It all started because I had an old iMac that I had for five years and it broke down. I felt like I couldn’t throw it away. So what I decided to do was take it apart. And once I took it apart I found all the pieces interesting and I wanted to create jewelry or something with it. Long story short, I came across this story of China or Japan, where there were three hundred employees that were on top of a roof, they were going to commit suicide because they were not treated right in their work area. I forgot for what computer company, but when I opened up the Mac I was like ‘wow, this is intriguing, this is a lot of work put into one computer.’ So I wanted to exhibit artwork that represented and showcased those workers.

I ran some of the motherboard through the press, and inked it. And I did some etchings. I used flies, rats, roaches in the imagery, my interpretation of them, because that is how these people were treated as humans.

I did this painting of a big old chunk of steak in the shape of the United States. I wanted to showcase that we are the meat and potatoes of the world. People come from afar with nothing in their pockets, don’t know the language when they get here, all to get a piece of the steak. It’s a huge painting, and I hung it on barbed wire. Barbed wire represents to me you have to cross the border, you have to cross the lines. It’s forbidden to come over here. But if you get pass the barbed wire…

KJ: You get steak?

CC: [Laughs.] Yeah, you get steak.

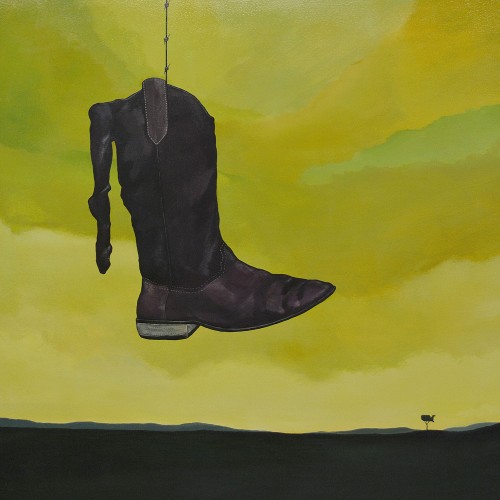

KJ: What about the one that features the boot?

CC: The boot is in the shape of Mexico and also hung from barbed wire. The barbed wire represents people who had to cross the border. The boot comes from a story my father told me about when he came over illegally. There were several times where he was hired to come over to pick fruits and vegetables. There were times when the United States would actually go and get Mexicans to work here with papers. But, there were other times when my father had to cross the border illegally. He’d have to pay a coyote, which is the person you pay to cross you over. My dad told me he’d put his money in his boot, because you never trusted the guy who was going to get you across. Or, if you were chased or robbed, the last thing they would take is your boots. I mean, if they take your boots they’ve taken everything. [Laughs.]

So I wanted to create imagery of my dad’s story. Also, you’ll see the United States tree way in the distance.

KJ: You work a lot with the shape of the United States, borders, and birds in your work. What significance does these themes have for you, and how has that significance expanded through your career. Have you always used these symbols?

CC: The United States symbols came later in my career. But I embraced the bird more as a symbol of freedom, flight. To be able to go to Mexico and come back to United States freely—I wish the world was like that, where we didn’t have any borders and we could go from one place to another.

Birds symbolize a spirit of freedom. They’ve come into my life, not just my artwork, often. I have interesting stories of crows. I’ve walked everywhere till I was 25. I never had vehicles, my parents didn’t have vehicles, and so I’ve always walked or taken the bus. So the majority of times when I was walking by myself and thinking about things somehow a crow would appear, so I always felt a connection with them. I don’t know if it’s because I am intrigued with them, but I always seen them do interesting things. Their knowledge fascinates me.

KJ: How long have you been an artist? What/who inspired you and what continues to inspire you?

CC: The inspiration for being an artist was my grandmother. She did a lot of pottery and weavings with palm fronds. She would create flowers, crosses, tortilla holders, mats, intricate designs. She was even asked to weave one for a famous Catholic Church in Mexico City because word had spread of her work. There was a TV channel that interviewed people from different towns, well, they came to our town and interviewed her. That was an inspiration for me.

KJ: Now what town do your people come from?

CC: San Pedro de la Cueva [San Pedro of the Cave] in the state of Sonora.

KJ: You’ve been very forthcoming about your battle with dyslexia. You don’t have to disclose it, but you chose to, why?

CC: I just think it’s important because a lot of people don’t. It’s been embraced more now, but when I was younger it wasn’t. I didn’t realize I was dyslexic until I got to college. I believe many teachers thought because I spoke Spanish I was trying to translate and so things got confused. So I was in Special Ed classes through high school, which allowed me to be more creative. [Laughs.]

About a week into college my professor told me to go see a counselor to see if I had a learning disability. I had to take a test and sure enough I was dyslexic. My whole world changed, which sucked because I had to restart the whole engine. I had to relearn English, relearn reading, math.

I really tried hard. I had friends who had other people write their stuff, but I really wanted to do it on my own. It was very frustrating and stressful. I still remember the day I was riding down the highway and I just saw it all as a boxing match—me fighting with dyslexia against what you consider an average normal person going to college and getting their degree. And so I was fighting myself, questioning if I should continue. My counselor would tell me, “you’ll get there, it’s just going to take you eight years.”

But that’s what dyslexia is and I was never afraid of telling people about my fight: showing people that you can get things done with dyslexia. I traded a lot of artwork for people to help me write. Or I helped other people in my creative work by doing graphics, logos and in exchange they would read something for me, write something for me, respond to an email for me.

Dyslexia is not a disability; it’s actually a gift. Dyslexics think differently. The normal brain, the normal institution makes you believe that two plus two equals four. But my brain makes me believe that I can add one plus one, plus one, plus one to get four.

KJ: Do you feel like the life of an artist includes sacrifices or compromises non-artist does not have to make? If so, what’s the trade-off?

CC: I sort of wish I was not an artist sometimes. [Laughs.] Its not like I chose it, people say, “well you can stop being an artist.” No, you can’t.

It’s like you look at something on a table and you see something different. Someone throws something away and you think, “I can make something out of that.” You look at your garden, everybody plants their roses in a single file line, and you say, “I want to get a yellow one, blue one, and make a face out of them.”

Being normal as in you wake up, take a shower, go to work, have lunch with your buddies in the office, come back home, have dinner, watch TV, weekends free, benefits, dental, health, vacations, save money for retirement. I don’t have those things, but I feel like I’m retired dealing with no retirement money. [Laughs.]

Yeah, there are trade-offs. They should put that in the dictionary. Artist means to struggle. It shouldn’t be, a creative person who likes to work with different mediums. No, you’re struggling. [Laughs.]

KJ: Thank you, Cosme; it was a pleasure.

CC: You’re welcome, and thank you.