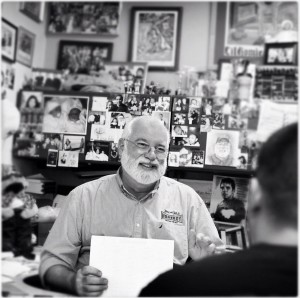

Gregory Boyle, Author and Activist

Gregory Boyle is a Jesuit priest and founder of Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles. Father Greg worked with Christian Base Communities in Bolivia, was chaplain of the Islas Marias Penal Colony in Mexico and at Folsom Prison in California. He was appointed pastor of the Dolores Mission in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles in 1986. In 1988, he worked with the parish to create Jobs for a Future (JFF), a program to help meet the needs of young people involved with area gangs. JFF has already established a school, a daycare center, and an office to help young people find meaningful employment.

In 1992, Father Greg began his first community business, Homeboy Bakery. The company provided training and work experience for gang members. In 2001, the ministry was transformed into an independent, non-profit organization called Homeboy Industries. Today, Homeboy includes a number of different business enterprises. 2010 saw the release of Father Boyle’s book Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion, recounting twenty years of experience working with young people growing up in a world of poverty and violence.

John Paulett spoke to Father Boyle by phone. During the conversation, Boyle spoke about some of the influences on his work, including Dorothy Day (founder of the Catholic Worker Movement), Cesar Chavez (co-founder of the National Farm Workers Association), and Father Pedro Arrupe (a major figure in the growth of the social gospel in Latin America). He also reacted to the Vatican’s recent criticism of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious for its emphasis on social justice over doctrinal issues such as contraception, abortion and same-sex marriage.

John Paulett: I was struck by the subtitle of your book Tattoos on the Heart, which is “The Power of Boundless Compassion.” Why do you think compassion is the power we need in order to address problems of violence and poverty?

If Jesus were to compile his top ten grave moral concerns in the United States, most assuredly on that list would be the growing gulf between the haves and the have-nots.

Fr. Gregory Boyle: First, I need to make a full disclosure. That was not the subtitle I had originally planned. My editor added that because she didn’t like my first suggestion. She came up with “The Power of Boundless Compassion.” I remember I was in New York City when she told me this, and then I couldn’t sleep that night. I emailed her in the middle of the night and said, “Please don’t do this.” Because I thought it sounded like I embodied this power of compassion—that, in some way, I knew how to pull this off on my own. So all she wrote me back was “Relax!” Hence was born the subtitle so I don’t want to take too much credit for it. Having said that, I think it’s good. In the end, it’s about a certain kind of compassion that is not just about our service of those on the margins but rather about our willingness to see ourselves in kinship with them. So it is more connective than distant and it stands in awe of what the poor have to carry rather than in judgment of how they carry it. It is a whole kind of sense, even though there is only one chapter on compassion. The whole book tries to lead us to a different place of connection and to bridge the distance that separates others.

JP: You mention early in the book that you watched eight young people be buried in just three weeks. What ideas have you developed about how we might address the problem of violence in our cities?

GB: Gang violence is a language. It is not about anything. It points beyond itself. It is not about conflict. That is important. Gang violence in particular, but I suspect all violence is a language. It is not about behavior. It is about the lethal absence of hope and hope that cannot be imagined tomorrow. It is about folks who are so traumatized that they cannot see their way clear to transform their pain so they continue to transmit it. And the big elephant in the room is that it is about mental illness. We never think it is about that. So a seventeen-year-old can gun down eight students. Or, in Afghanistan, a soldier can just wipe out men, women and children and yet no one talks about mental illness. They try to find a motive because everybody wants violence to be rational action, perpetrated by rational actors. I would say it never is—never. So it is a little bit like in the gospel when Jesus would heal somebody possessed by a devil. That is how anachronistic this is when we bring the moral overlay into the area of violence. I think we need to understand what language violence is speaking before we can begin to figure out what to do about it.

JP: Who were some of the people who were important to you in forming your ideas about justice and social activism?

GB: Well, definitely Dorothy Day is a hero of mine. I have read everything and I am, right now, reading, with great care, her whole unedited diary, which is pretty mundane but there are certain gems that leap out. So Dorothy Day, Cesar Chavez, who was a friend, Martin Luther King, Pedro Arrupe, who was Superior General of the Society of Jesus. I was privileged to meet him.

JP: As you have observed the Occupy Movement and the protests of The 99 Percent who feel more and more excluded from the economic life of the nation, what reactions have you had?

GB: I was sort of alarmed to hear Cardinal Dolan talk about the grave moral concern of Obamacare and the hubbub about that. I thought that if Jesus were to compile his top ten list of things that were of grave moral concern in the United States, most assuredly on that list would be the growing gulf between the haves and the have-nots and the huge disparity that grows all the time. That would be on there as well as the death penalty and the fact that we still sentence children to die in prison. The list is long but it wouldn’t include the things that some people get excited about. Certainly, high up on the list would be this distance between the rich and the poor. It seems to me as bad as it has ever been.

JP: The United States Bishops and the Vatican have recently criticized the leadership of American Catholic religious sisters for their emphasis on social justice instead of issues such as contraception, abortion and gay marriage. Have the Sisters been involved with your work at Homeboy Industries?

GB: Over the years, we have had a couple [of religious nuns] teach in our schools and, right now, we have a Sister working as an intern with us [at Homeboy Industries]. That move [by the Vatican] is an alarming development. I was at a talk yesterday and some very old woman said, “I felt hopeful for the Church for one very brief, fleeting moment when the bishops said that a budget is a moral document and spoke against the cuts for the poor.” And I agree with her. It was a fleeting moment. Those are moments that you wish there were more of, as opposed to attacking the religious women in this country. You would be hard-pressed to find an entity or a body of Catholics who have lived the gospel with more integrity than religious women.

JP: I heard you speak in December [at Antioch] and wrote down this line from your talk: “We are all so much more than the stupidest things we ever did.”

GB: I am stealing [that line] from Sister Helen Prejean. “Everyone is a whole lot more than the worst thing we ever did.” That is her line. I put in “stupid,” but the line is really due to her. No one would want to be defined by the worst thing he has ever done. You wouldn’t want to say that one moment, that split-second, when you did that one thing…that somehow defines the entirety of who you are. Which is what we do in our society. You can’t do anything wrong, and you can’t make a mistake, and you can’t have anything wrong with you. It is one of the rules of society.

JP: The title of your book is Tattoos on the Heart. Does that refer to the way people are sometimes defined by things such as tattoos, or as we saw in the Trayvon Martin case, by clothing such as hoodies?

GB: Tattoos on the Heart came from a story about a kid. I had praised him, rather unexpectedly. He got all choked up and said, “I am going to tattoo that on my heart.” I remember, when he said it, in my head I said, “That would be a good title for a book.” The title really preceded the book’s arrival by about ten years. Homies often tattoo their kids’ names or sometimes even, quite elaborately, a baby picture of their kid and I’ve always said, “No, no, no. Your kid wants you to tattoo him on your heart—not on your skin.” That should convey how deep the love goes.