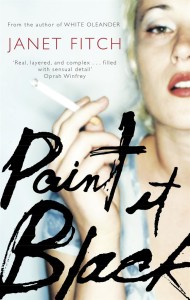

Janet Fitch, Author

Janet Fitch is a long-time lover of history and Russia. During a student exchange in England, Fitch realized she wanted to be a writer. She published her first book, Kicks, in 1996. After her second book, White Oleander, made the Oprah Book Club, she was swept up in a whirlwind of critical acclaim. In 2002, “White Oleander” was made into a movie and just four years later Fitch published Paint It Black. She lives in Los Angeles and is presently working on a new book set in Russia.

Janet Fitch is a long-time lover of history and Russia. During a student exchange in England, Fitch realized she wanted to be a writer. She published her first book, Kicks, in 1996. After her second book, White Oleander, made the Oprah Book Club, she was swept up in a whirlwind of critical acclaim. In 2002, “White Oleander” was made into a movie and just four years later Fitch published Paint It Black. She lives in Los Angeles and is presently working on a new book set in Russia.

Tai Farnsworth: Your book Paint It Black is in production to become a movie. Did you ever imagine that this short gothic story would grow into a book, and then into a film?

Janet Fitch: What I end up writing, it’s always a surprise. Some small kernel of inspiration, which magnetizes other concerns and moods and characters, a small stream joining to other small streams, growing wider and deeper. It’s interesting, that this book began with a favorite film, Bergman’s Persona. Then I took that inspiration and wrote a short story, which then, following a strange twisted pathway, became a literary novel. And now—based on a reader’s enthusiasm for the book—it’s going to become a film—a very different film from the original inspiration.

TF: White Oleander was so brilliantly cast. You probably don’t get any input, but do you have any thoughts on who you’d like to see as Josie or Meredith in Paint It Black?

TF: White Oleander was so brilliantly cast. You probably don’t get any input, but do you have any thoughts on who you’d like to see as Josie or Meredith in Paint It Black?

JF: I do, but I can’t go too far into this because there will be a Josie, and a Meredith, and I won’t have chosen them. I always saw a Meredith as kind of a combination of Marisa Berenson and Anouk Aimee…actresses from the sixties and seventies, so no way could they play Meredith now in any case. And Josie was based on a friend of mine, as she was at 19, so I’m looking forward to seeing a 19-year-old—who would have been all of 7 or 8 when I started writing the book. But I’m hoping for someone equal parts fragile and tough, elegant and punk.

TF: What does it feel like to have your books turned into movies? Are you worried about not liking the result? Does it feel exciting or nerve-wracking, or both, to have your work reach a whole new set of people?

It can’t ever hurt a book—if it’s a good movie, it will bring people to the book, if it’s a bad movie, people will say, “Oh the book was better.”

JF: It’s a great pleasure to have books turned into movies. A film allows the book to reach an entirely new set of readers. It can’t ever hurt a book—if it’s a good movie, it will bring people to the book, if it’s a bad movie, people will say, “Oh the book was better.” Either way, more people find the book. You hope it will be a good movie of course, but you have to just let the filmmakers make their film. You have to know it’s not a miniseries, it’s not going to be a word for word translation. Someone is making a work of art inspired by my work of art. That’s flattering as hell.

That said, I think it’s harder on readers who love a book—and hope to see that book on the screen. When filmmakers have departed significantly from the book, especially aspects of the book they particularly liked, it’s always disturbing. But to take a 450-page book and turn it into a 2-hour movie, significant portions have to be left behind. Filmmakers have to take what they feel to be the most significant part of the book, the mood, the central drama, and let the rest fall away.

And if I end up not liking the result, well, I didn’t have to make the movie! It’s a very difficult process and something I would not want to have to do myself. I wrote the book. I’ll write another book. It’s just flattering as hell.

TF: Your next book is also likely to appeal to an entirely new group of readers. Russia has always played a big part in your life. Is it comforting to find yourself back working on something so directly related to your first love?

JF: I don’t think comforting describes the sense of being engulfed by an immense historical novel. It’s more like being swallowed by a whale. Like Ahab, I have my own obsessions. Russia is my Moby Dick, I hope it doesn’t kill me. Then again, I’m not trying to kill it—I’m trying to capture it alive.

Still, it is incredibly satisfying to explore a time and a circumstance in Russian history I always wanted to examine. Everybody in the West writes about the Stalin era and World War II. But the Revolution…even the Russians didn’t know that much about it because the history had been rewritten so frequently…and now there is access but politics continues, people have their own agendas. And revolutions have a peculiar logic of their own—what they start out as and where they end up, that is of keen interest to me. I’m very interested in the psychological and moral process by which people believe in things, believe in ideas—what do they do when the idea they have fought so hard for doesn’t match up with the unfolding reality? Do they admit it? Do they continue to defend the idea, which is becoming a lie?

I love spending this much unbroken time in this fascinating time and place, these terrific characters, completely non-American. There’s a challenge, trying to inhabit a Russian sensibility through the progress of a big novel. But my first idea of what a novel should be was the Russian novel—Dostoyevsky in particular. So my love of Russian literature preceded my interest in Russian history. Without the Russian novel, I don’t know if I would have undertaken anything this ambitious. Sometimes I see what I’m doing and I just freak out. But I keep telling myself, an ant can move a mountain, one grain at a time.

TF: Are you worried that people who are attached to Los Angeles as the setting and one of the main characters of your books will be disappointed you’re moving away from that?

JF: That remains to be seen. I think it would depend if it was Los Angeles per se people are attracted to in my work, or my sense of place generally, and how that is always intrinsic to the story. If it’s the latter, I’m on safe ground—the Russian novel is set in revolutionary Petrograd [St. Petersburg during the ten-year period between WWI and the death of Lenin in 1924]—and I’m absolutely obsessed with that city. I was an exchange student there during the Soviet era, and have gone back twice for research….I hope if I do it justice, that people will recognize my hand.

TF: When Los Angeles is the focus do you do a lot of your writing in the diners, restaurants, bars, or popular sites that your characters frequent? Do you ever drive around Los Angeles looking for inspiration?

JF: First question no, second question yes. I don’t need to write in the locations I use—I know them. Like, do you need to do research about your grandmother’s apartment? Sometimes you are creating something that isn’t even there anymore.

Second question—I see things that inspire me every day. Driving around, walking around is even better. Driving is just an instant. Walking, you can stop and consider. Sitting and hanging out and watching is the best of all.

TF: Do you ever regret moving away from history? Do you think being a historian would have been an easier career path? Would it have mattered?

JF: Writing historical fiction is the best of both worlds, I can do the research and ask the questions, but I can do what I love best, writing fiction—inhabiting and bringing historical phenomena to life through the point of view of a single human consciousness. I never really moved away from my love of history, only from my pursuit of a career as an historian.

TF: How many hours a day do you write? What does that writing process look like? Are there outlines and pre-writing or mostly just rough drafts? Do you have to be alone? Do you listen to the music that’s so woven into your stories?

No outlines. I know, scary. I usually start with a character and a situation that’s already wound up, like a little spring toy, you wind it up and you let it go.

JF: I usually write about four hours a day, more if I’m on a roll. I do rough drafts, rough rough drafts, and rewrite and rewrite as I go along. I also write short shorts on my blog, www. janetfitchwrites.wordpress.com, for the pleasure of finishing something! I might write from prompts or scents or objects, just to tune up, or even use a photograph related to my work and write my way into it. If I’m completely flummoxed, I might go somewhere and write, throw headphones on and listen to something droning, like Bauhaus, or Russian Circles, or London After Midnight…

I have used music to keep me in a mood—when I was writing Paint It Black, I had a tape called The Saddest Songs in the World I used to put on when I was feeling too cheerful to write it. I was in a very dark place when I started the book, but it takes me four or five years to write a novel, and by the time I was finishing it I was in a very different place. The Russian composer I listen mostly to is Prokofiev, it gives me the right feeling.

But mostly, it’s silence, so I can hear the music of my own prose. I often read poetry before I write, so that music is in my ears—Dylan Thomas, T.S. Eliot (especially the Four Quartets), Joseph Brodsky, sometimes Allen Ginsberg. Ear-poets.

No outlines. I know, scary. I usually start with a character and a situation that’s already wound up, like a little spring toy, you wind it up and you let it go. It sometimes takes me up a blind alley, and I have to back out and find the story again, jump ahead or switch point of view for a little to find myself again. But I like a stable unified point of view. In each book, I have tried writing from more than one person’s point of view and ended up discarding the various voices for the one strong central character—much like pruning side blossoms to encourage one big bloom.

But for me, place is everything. I have to know WHERE. If I know WHERE, everything else comes. Crazy, yeah? Maps have been hugely important to the writing of this Russian novel.

TF: What would you say to budding authors who are worried about working in a field that is so rife with rejection and subjective reviews? How do you keep the motivation going? Do you ever get to a place where you can think, “Who cares what people say? I’m Janet Fitch!”

JF: Hahahahahaha. Janet Fitch, what’s that? A writer facing doubt and terror every day, who also has problems and has to pay the rent and so on. What I’d tell those budding writers is—don’t worry about the competition, just make what you’re doing as excellent as it possibly can be. Keep learning, find people you trust and listen to their critique. Read the best, read like a writer—which is like being a magician, don’t just sit out front in the audience gaping like an idiot, watch and figure out how the tricks are done. Pull people’s sentences apart and see how they’re constructed. Learn the craft, aspire to greatness. Motivation—a lot of this is what Paint It Black is about—how all artists have to live on a sliding scale between permission and perfection. There is no set point. Sometimes we cut ourselves too much slack and have to hold our feet to the fire. Read something insanely beautiful and become reinspired. At other times, the greatness of others paralyzes us, and then we need to cut ourselves more slack, give ourselves permission just to make a sound. Punk rock.

Yes, there are moments when you think, “Dang I’m good!” But I mean, these are MOMENTS. My writing teacher Kate Braverman used to say, “There’s no such thing as a permanent state of grace.” You come down from that mountain pretty fast. And then you’re just working again. You never know if it’s any good, really, until the book is in the hands of its readers. The worst moment is when you get the galleys back—the first time you see it set in type, the way it’s going to look on the page—and GOD it looks terrible. But I’ve been through it twice now, and I know, that’s just the way it is.

Rejections—it’s about making it as good as you can, using every resource available, refining your skills as brightly as firing a sword, and then braving the numbers game. Reviews—terrifying. I usually make someone else read them first. I’m very thin skinned; I take everything personally. I just keep reminding myself, not everybody likes chocolate. Not everybody wants a dirty martini. Who are you writing for? Do you want to be a bag of Doritos, or do you want to be an interesting highly flavored appetizer, or do you want to be a four-course meal? Everyone has to answer these questions for themselves.