My Hilarious Depression

I like to tell people—uncomfortably early in the conversation—how I’ve had three times more therapists than lovers. When someone asks me why I stopped responding to email communication for two weeks, or why I disappeared from Facebook for three months, I might say that I was busy weeping under my desk while curled up in the fetal position. I tell people that I can’t go out on Wednesday because I’m scheduling that night to bathe in a tub full of gin and self-loathing. Or that I can’t go out to lunch because I’d like to dwell on the accumulation of my failures. I can’t make it to the party on Friday night because I am too upset about being u nable to masturbate due to an overwhelming sensation of self-disgust.

nable to masturbate due to an overwhelming sensation of self-disgust.

There are some exaggerations here. I occasionally just go for a cheap laugh at my pathetic persona’s expense. But every one of those excuses stems from a truth about an emotion that I know well.

Depression wasn’t initially so amusing to me. It used to be that everything I wrote or said about the subject was oozing with melodrama. Poor, poor me. I took myself and my mood so damn seriously. (I have a notebook full of failed essays and stories that start with the actual line: “I’m so damn depressed.”)

It’s tricky to navigate this terrain. Depression can be dangerous. It merits serious attention and often requires outside support. Even if you don’t go through bouts of suicidal tendencies or rate highly on the spectrum of clinical depression or get into a destructive habit like self-mutilation, it can still eat into your body and soul, cloud your view of the world. It distorts. It destroys friendships and relationships. It weighs on your shoulders, day and night.

There was a time when I spent afternoons curled under my desk crying. I would brood over arguments I had with my father ten years prior. I re-enacted every trivial scene in my day, thinking how stupid everything I said was. Even an unmemorable, awkward moment with a cashier at the grocery store could crush me. And, like the main character in my first novel, I secretly cut myself on my waist and arm and ass while brooding about what a failure in life I was (even though I was successfully making my way through an engineering degree while hanging out with a group of fabulous friends).

With the help of a series of therapists and a few phases of anti-depressant medication (one of which caused nightly dreams of tarantulas crawling on my crotch, but made me happy enough at the time to feel that it was worth the spiders), I’ve gotten a glimpse of what it feels like to live as a non-depressed person.

It is fabulous. It is clean. It is easy. I never knew it was possible to walk around with so little dread and self-hatred. I never knew it was legal not to be paralyzed by a sense of failure. I used to assume that any person of depth spent most of their time disgusted with who they were, and only fools could walk around feeling okay about themselves. I figured it was the price of living a non-superficial life. And so I was uneasy with that feeling of easiness. Like the last moments of drunken joy before a hangover too severe to Advil away. But it turned out there weren’t any repercussions. I don’t walk around all day in this illegally easy state, but I’m happy not to hate myself most of the time.

I’ve also grown a new appreciation for my depressed state. It’s heavy and horrible, but there is also a sort of gravity in there that adds a level of reflection and poignancy to life that I might have missed in a simpler, happier state. There’s something in there that I can carry into my healthy life. Now when I look up at the sky and take a breath and think that it’s a beautiful day, I’m also aware that there are moments when I (or another person) can’t imagine what the stupid fucking sky has to do with beautiful. There are moments when the idea of something beautiful seems impossible and greedy and disgusting. This awareness makes the beauty at that moment seem so much more potent. And fragile.

I’ve also grown a new appreciation for my depressed state. It’s heavy and horrible, but there is also a sort of gravity in there that adds a level of reflection and poignancy to life that I might have missed in a simpler, happier state. There’s something in there that I can carry into my healthy life. Now when I look up at the sky and take a breath and think that it’s a beautiful day, I’m also aware that there are moments when I (or another person) can’t imagine what the stupid fucking sky has to do with beautiful. There are moments when the idea of something beautiful seems impossible and greedy and disgusting. This awareness makes the beauty at that moment seem so much more potent. And fragile.

There’s a silly bit of dialogue in the movie Rushmore between the fifteen-year-old Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman) and the older Herman Blume (Bill Murray) that I can’t stop thinking about whenever I talk about going through a difficult experience:

Max Fischer: So you were in Vietnam?

Herman Blume: Yeah.

Max Fischer: Were you in the shit?

Herman Blume: Yeah, I was in the shit.

It’s that quick use of the phrase “in the shit” that I love, a connection between these two about a traumatic experience that occurred to Herman long before Max was even born. In one way, it’s funny because of course this child doesn’t understand the experience of a soldier who fought in a war. But I also like this moment because maybe he does understand it. Maybe this kid had his own war already.

I think about all the amazing creative people that I know. Almost all of them were in the shit. Sometimes, it was an actual war. Other times, it was depression. Or abuse. Or addiction. Or dealing with being gay in a hostile environment. Or divorce. Or grief. Or having to sit through the entire Lord of the Rings trilogy on video. Being in the shit often delivers (along with the shit) some wisdom.

I talk about transforming my depression state into a productive writing state in this short video I made last year for my “I’m a Failed Writer” series.

I learned this other thing about depression: it is pretty damn funny.

Without trying to conjure up a great philosopher, there’s an absurdity to our existence. Depression can accentuate that absurdity. It can push life close enough to the edge of the cliff to make the whole proposition of existence seem crazy. And why not be amused by that?

You can’t tell me it isn’t a little funny that in my college years, during my weekend visits to my girlfriend’s place, I would cry on Friday night because I was depressed about it being so close to Monday. Some weekends I destroyed every single minute of the visit. Sad. Pathetic. But funny, a little bit…?

It took some time to learn where the humor was in all of this. It started by reading my early stories aloud in a writing group. I was still writing mostly melodramatic autobiographical stories, but I noticed that the other writers were laughing when my main character (usually named Yuvi) kept worrying and brooding and obsessing in destructive ways. My first instinct was to be offended. Why is it so funny that my main character wants to hide in the closet with his girlfriend and cry about his feelings all day? Who wouldn’t want to do that? But over time, I started to see the humor in it myself. And so I intentionally tried to walk a line that would be keep the story funny, but also have a touch of poignancy and humility in there.

It took some time to learn where the humor was in all of this. It started by reading my early stories aloud in a writing group. I was still writing mostly melodramatic autobiographical stories, but I noticed that the other writers were laughing when my main character (usually named Yuvi) kept worrying and brooding and obsessing in destructive ways. My first instinct was to be offended. Why is it so funny that my main character wants to hide in the closet with his girlfriend and cry about his feelings all day? Who wouldn’t want to do that? But over time, I started to see the humor in it myself. And so I intentionally tried to walk a line that would be keep the story funny, but also have a touch of poignancy and humility in there.

Even if my humor is an attempt to point out the ridiculousness of some depression-induced behaviors, I think I also try to simultaneously pay tribute to that state of existence. I want to light a candle to the experience, to the people going through such heaviness. In the midst of being in that state, it is hard to imagine that any other feeling can exist. But if we get to the other side, we can discover something remarkable we wouldn’t have noticed otherwise.

I discovered a type of humor that allows me to expose my fears and weaknesses and mood problems in a way that gives me such a relief.

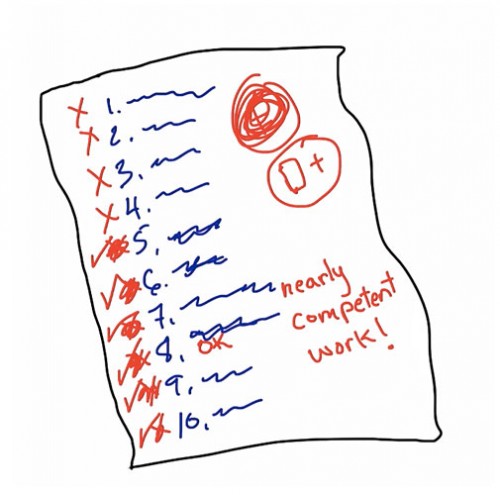

Though it also doesn’t hurt that I really really like my latest therapists. All three of them.