Writers Read: Night Sky With Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong

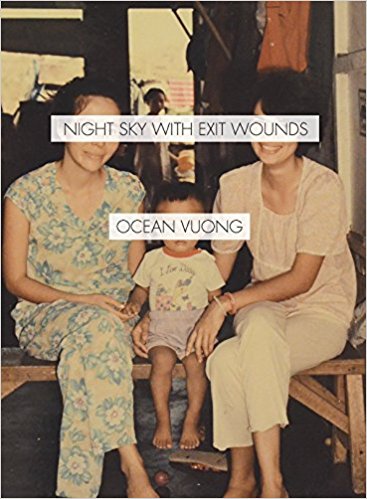

Night Sky With Exit Wounds is woven from deep threads—the experience of fleeing war and becoming a refugee, migration and the sea, parent-child relationships, and queer sexuality. Life is complex. Layers of emotion, memory, and transformation unite in this journey of one human being.

Night Sky With Exit Wounds is woven from deep threads—the experience of fleeing war and becoming a refugee, migration and the sea, parent-child relationships, and queer sexuality. Life is complex. Layers of emotion, memory, and transformation unite in this journey of one human being.

Vuong’s stories and structures made me feel huge possibilities in poetry. He uses a variety of forms, and switches them up. My eyes and brain and heart read along appreciatively. Stanzas bite like jaws from either side of the page. An entire poem lives inside a footnote. He reminds us that poetry is a visual art.

The book begins with the loss of a parent and a refugee’s journey across the ocean. A shift in tone starts with his poem, “the Torso of Air.” Maybe hope awaits us on the other end of a tiny passage way. I love the way he digs through a wall to find happiness—the size of a coin—staring back at him (55). Thank goodness. Without some kind of hope, his gorgeous and masterful book might have dismembered me.

His existence is a kind of miracle. I loved and respected his use of nature and family, pain and love, violence and connection—all drastic, dramatic juxtapositions that exist in life. He resurrects his family migration and war stories to honor their resiliency and track his own healing.

I like it when a book enters my life. Vuong did that. On the first page of the book, I scribbled in pencil “Beautiful. Nature bigger than human language.” I photographed some of his poems and found myself reading one aloud to the woman next to me at a birthday party dinner table. She was someone I’d never met. While teaching, I found myself using Vuong’s “They say the sky is blue / but I know its black” with my high school students when a discussion ensued in class about our associations with skin color (black and brown and white). I found myself defending the fact that the sky is black and welcoming, all encompassing and impressive—a palate that frames our dreaming. I found myself coming to the defense of the black sky.

Vuong helped me rethink the connection between the body and love. Sexuality can be a kind of ontological homecoming. Maybe the body is what’s real—the body, not love per se. He writes about the body as language: “His hands. His hands. The syllables inside them” (13). Also, why else would he be thank you-thank you-thank you-ing a guy he made out with in a baseball dugout even though he didn’t know or love him? “Let every river envy our mouths,” he writes. “Let every kiss hit the body” (13). Sexuality can help us access somatic knowledge. “Give the body what it knows,” he writes (43). Vuong reclaims masturbation as a natural, and perhaps holy, act worthy of an ode. For example, semen becomes “holy water smeared between your thighs” (62). He explodes the supposed Cartesian split between mind and body and upends the hierarchy between love and desire. “I thought love was real and the body imaginary,” he writes (48). Maybe it’s the other way around.

Love finds a way in this emotional chronicle. I felt his love for his mother. Her love for him was elemental. I felt his longing for his father, but could not grasp what actually happened to the man. He puts his [father] in brackets in the dedication, then kills him in the first poem, or maybe he is saving him? I did want to know what happened to his Dad. Near the end, he identifies a love shared with a partner.

I have a lot of respect for this writer. I searched for interviews online and found his oral storytelling equally compelling to his writing. While he is the first one is his family to wield a pen, he claims his literary legacy in his community’s oral singing, praise, and storytelling. He is not the first writer in his lineage if, as he says, “the body is the book.”

Vuong, Ocean. 2016. Night Sky With Exit Wounds, Washington: Copper Canyon Press.