Mind Maps: The Bridge to Clarity

I walked into the house one night last week, my clothes soaked, my legs jelly. I was desperate for a shower and something to eat.

“How was your swim?” my fifth grader asked, looking up from her drawing. And then, “Wanna read my essay?”

The swimming reference is our little joke, since the studio where I spin is heated. Afterwards, it always appears as if I had jumped fully dressed into a swimming pool. The living room air was chilly compared with the class I had just left, and my hair was dripping down my back. I made a beeline for the shower, calling back to her that I’d happily proofread the essay when I got settled with something to eat. Thirty minutes later, there I was at the dining room table. Plate of food, bottle of water, and plunk! eight paragraphs of penciled cursive. An essay titled “The Middle Colonies.”

I read it carefully—mostly because I want to stay involved with what the kids are doing, partly because I’m the household copyeditor, and a little bit because, truthfully, I always learn something from their schoolwork. She’s on American history at the moment. Her class is studying regions of the country where I was raised but she’s never been. I pictured the layout of the middle colony states, the Delaware River, the old towns I knew in New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania which were named after the tribes who, because of the colonies, no longer call those spots home.

I don’t expect to receive life-changing lessons from my kids’ school projects, but this time I did. Life-changing, I tell you. Practical and well-timed. Uncannily well-timed, actually.

You see, lately I’ve been at work on my own research-based essay. The topic is one dear to my heart—the wicked stepmother narrative. I’ve been digging into the lurid stereotype’s history, how it negatively impacts stepmothers and their families, and our society’s need for counter-narratives. I recently completed the first draft of my paper. Man, there’s interesting stuff in my pages, but the structure is in shambles.

My fifth grader’s essay, on the other hand, is remarkable. Her structure is perfect. The entire essay begins by establishing the broad topic. After the introductory paragraph, each additional paragraph opens with a topic statement, utilizing transition words to pivot from previous ideas into new, and then developing the new ideas further with supporting statements. The whole essay is eight paragraphs of clearly organized material. I was truly impressed with her writing. And humbled. Structural organization is exactly what I have been struggling with in my own essay, multiplied by forty pages.

It’s not that I expected my kid to hand in a poorly done project—she hates school, yet takes pride in her work—however, the skilled construction of her writing surprised me. It indicated orderly thinking, an ability to envision a framework for her ideas, and a skilled transfer of her vision into linear, verbal expression. This is exactly what I’ve been struggling with in my own stepmother essay: the architecture. Somehow, it’s the very thing my ten-year-old has mastered.

After the bedtime shenanigans later that night, while straightening the dining room table, I gathered her school papers into a pile. Poking out from the edge of her binder was a folded 11×17 page. I could see circles and lines and words about “The Middle Colonies.” Curious, I unfolded the paper onto the table.

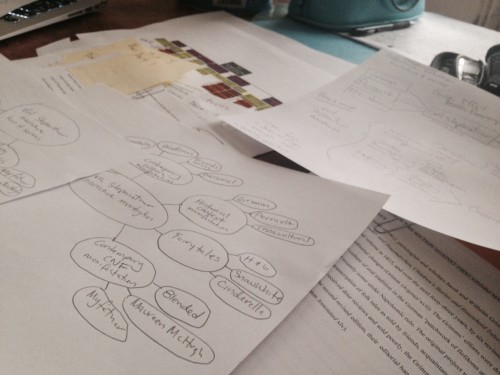

In the center was her topic title inside of a circle highlighted in green. Surrounding that circle were eight others, highlighted in pink, with arms extending to the center circle. The pink circles were sub-topics, labeled with words like “hardships” and “where they came from” and “industry.” From each pink circle was a group of three or four yellow circles, each containing basic supporting facts. Clipped to the 11×17 paper were strips of colored paper with full sentences that corresponded to the ideas in the highlighted circles.

I looked further. In her notebook was a page titled “Thinking Maps®”. There were eight diagrams drawn and labeled: tree, flow, multi-flow, brace, bridge, circle, bubble (the one she used for “The Middle Colonies”), and a super-sized cousin double-bubble. After snooping in my fifth grader’s school binder (I am not too proud to confess), I took out my own notebook and began making notes from her school work.

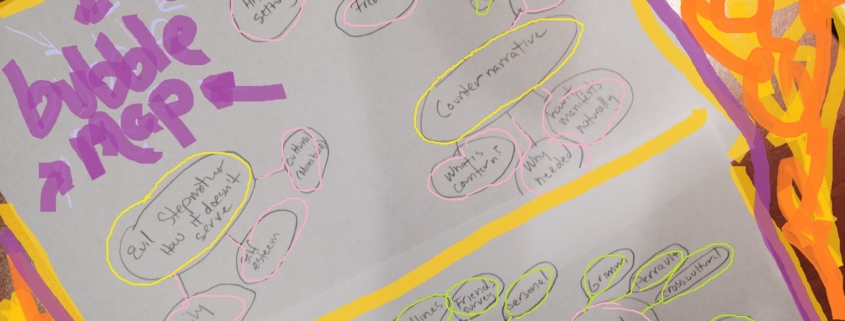

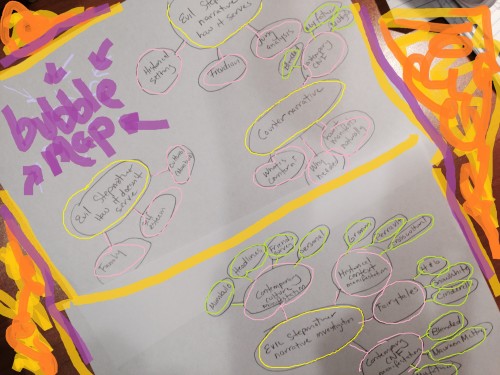

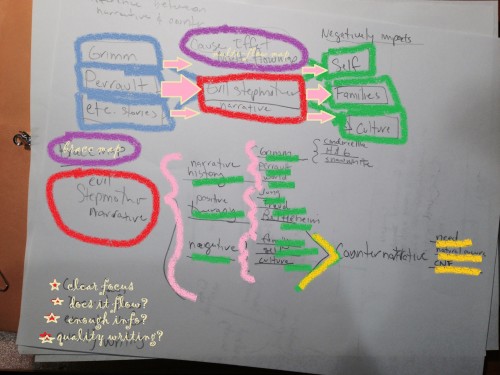

The next day, I mapped my stepmother essay. I grabbed a pile of blank paper and started with a bubble map. The non-linearity of this map shows relationships between ideas. It’s a web of concepts, and mine extended into multiple layers which plainly showed the research areas my paper examines. Next, I drew a multi-flow map to visualize my thesis statement. This helped me understand the straightforward origins of the wicked stepmother narrative, and the ways it affects society, the family unit, and the individual. A brace map then gave me a picture of the types of psychotherapy theories I had surveyed. Finally, I drew a tree map to translate the ideas sketched on the other maps into a sequential outline.

Seeing my “wicked stepmother” laid out in such an orderly manner untangled the past two months of research work. I can see now that my first draft of the paper is like the essay equivalent of a tornado-destroyed house: pieces of the kitchen are strewn across the front yard, the bedroom is half missing, the living room is snarled up in the playroom of a house down the street. With my maps in hand, I’ve now started putting things back in order. So far, draft two is feeling much more structurally sound.

Since discovering the mind mapping tools, I’ve been diagramming everything. Over the weekend, my sweetheart and I went on a date to discuss a backyard celebration we’re planning for later this summer. Before our server came with glasses of wine, I had pulled out a few sheets of blank paper and some pens. Food and drink ideas for the party? The decorations? Preparations for the house? All bubble maps.

This morning I mentioned that I was writing a blog post about “The Middle Colonies” essay and the mind maps I found in the notebook. His response?

“She tutors for a reasonable rate.”

He must have forgotten that I’m in graduate school. Even with the family and friends discount, I can only afford a one-time consultation.

However, if you’d like a tutor, let me know. Meanwhile, need a map?