Writers Read: Child of God by Cormac McCarthy

Cormac McCarthy’s third novel Child of God, based loosely on an infamous murder in Sevier County, Tennessee, portrays a cycle of extreme isolation, perversity, and violence as representative of the natural human experience. The novel tells the story of Lester Ballard, “a child of God much like yourself perhaps,” who, facing a series of unfortunate circumstances beginning with his eviction from his home, descends into the limits of desecration, and literally into the depths of the earth.

Cormac McCarthy’s third novel Child of God, based loosely on an infamous murder in Sevier County, Tennessee, portrays a cycle of extreme isolation, perversity, and violence as representative of the natural human experience. The novel tells the story of Lester Ballard, “a child of God much like yourself perhaps,” who, facing a series of unfortunate circumstances beginning with his eviction from his home, descends into the limits of desecration, and literally into the depths of the earth.

McCarthy reveals his worldview in exchanges of dialogue, such as this conversation between Deputy Fate Turner and a local old timer:

“You think people was meaner then than they are now?”

“No,” he said. “I don’t. I think people are the same from the day God first made one.”

McCarthy always leaves subtle clues for his readers and demands character names receive due attention, and Child of God is no different. The naming of the sheriff seems a curious choice because, like Deputy Ed Tom Bell in McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men, the lawman is no “turner of fates,” unable to bend the course of evil but only able to identify the victims and inventory the evidence.

By portraying Lester as a tragic character instead of merely an instrument of evil, McCarthy pushes the limits of propriety—murder, pedophilia, necrophilia. He paints a portrait of a troubled individual faced with morbid images throughout his life. Lester is orphaned: first his mother abandons the home, and then, as a young boy, he discovers his father’s body, grossly disfigured from the father having committed suicide by hanging. So begins Lester’s fascination with the grotesquery of death. Rejected in more conventional interactions, he finds that he is only able to achieve intimacy and fulfillment via necrophilia.

McCarthy’s obsession with death, or at least the ritualization of death, is itself rendered with what one could describe as literary necrophilia. Death becomes a ritual of courtship for Lester. McCarthy’s description of the execution of two murderers portrays the public event as something of a civic celebration. In another sequence, Lester recalls the death of a wild boar, taken down by dogs, with a balletic verve, describing the “lovely blood” as the boar spirals into death.

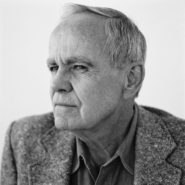

Cormac McCarthy by Derek Shapton

McCarthy’s style is minimalist and completely removed of excess and decoration, both in terms of grammar and punctuation. He experiments with an unfulfilled narrative trope, evidenced when he reverts to a third person narrative in the voice of an unnamed member of his community. Here and in subsequent work, McCarthy seems to be unable to separate himself from Old Testament themes: catastrophic flood, blood sacrifice, revelation in fire, then later and more evidently in the Biblical language of Blood Meridian.

Child of God adds to McCarthy’s canon of depravity and darkness, coupled with the thesis that humanity is dark and prone to great, catastrophic evil. On the other hand, in McCarthy’s view, nature is profoundly beautiful, as depicted in the touch of leaves and fronds upon Lester’s face as he escapes his cavernous underworld, a suggestion of benediction and peace with his deplorable acts. Ultimately, having surrendered himself to a mental asylum (“I’m supposed to be here”), when Lester dies, his body is consigned for dissection, as if clues to the evil in him can be interpreted, the way pathologists look for tumors and aneurisms to explain morbidity. Child of God demonstrates McCarthy’s view that nothing organic or occurring in nature can amount to the evil in humanity.

McCarthy, Cormac. Child of God. Random House, 1973.

Edmond Stevens first began writing for publication while in high school for his hometown Burlington Free Press. That led to positions with major New England newspapers and later The Los Angeles Daily News. Life in Los Angeles made for the irresistible transition to screenwriting. Edmond’s portfolio includes six made-for-TV movies and numerous network series. His most recent credit (2014) is Skating to New York, based on his novella. Teaching credentials include creating the screenwriting program at Utah’s Writers@Work, plus workshop appearances at Sherwood Oaks College, University of Utah, University of Southern California, Chicago Film Commission, and Sundance Institute.

Edmond Stevens first began writing for publication while in high school for his hometown Burlington Free Press. That led to positions with major New England newspapers and later The Los Angeles Daily News. Life in Los Angeles made for the irresistible transition to screenwriting. Edmond’s portfolio includes six made-for-TV movies and numerous network series. His most recent credit (2014) is Skating to New York, based on his novella. Teaching credentials include creating the screenwriting program at Utah’s Writers@Work, plus workshop appearances at Sherwood Oaks College, University of Utah, University of Southern California, Chicago Film Commission, and Sundance Institute.