How Baseball Saved My Life

Corner of Haight and Ashbury circa 1967

My family and I arrived in San Francisco in 1969, a couple of years after the Summer of Love, seven years after the San Francisco Giants’ last World Series appearance. A trail of incense and marijuana still wafted through the City. I was about to turn twelve, and it is that scent that I most remember, because it was new and it stank of drastic, indecipherable change. The cold and the streets crowded with people I neither knew nor understood cast out such distances between where I was, and where I came from, that I thought I’d never again remember home.

Only a week before, I had been in Havana, in the sun, embraced by the warmth of family. They had overwhelmed me with love, more than normal, in anticipation that perhaps it would be the last time they’d ever see me. I remember their tears each time they hugged me. I was in the known.

The Cuban Revolution was evolving and making every effort to eradicate western culture. Cuba was a place where long hair and American music were not permitted. A place where wearing bell-bottoms was an offense worthy of jail time, regardless of age. I’d hear adults argue about how their freedom was being systematically stolen from them. I’d hear them talk about leaving to the United States, where they could be free. But I never understood any of that. To me, there was only one thing: baseball, and my team was Industriales, Havana’s team.

* * *

I found that in this strange place even the Spanish I heard some people speak was not my own. My uncle, whom I’d never met before, was nice but still a stranger, as were my cousins. Everything that was home, that meant home, was gone and seemed irretrievable. I supposed this was what freedom was like, but I didn’t like it. Instead, I felt alone, trapped, and less free than I’d ever been.

For months, I wallowed in self-pity and melancholy; I missed the only friends I knew up to then, the family we left behind, the blue skies, the warm sun, the pounding rains, the slap of the domino pieces over the constant chatter of the players, the red clay stuck to the bottom of my shoes, drinking water from the hose, the sweat, the laughter and the music. We all did, my sister, my brother and me. It was worse for my mother, Mima. She wanted to carry that burden for all of us, but her task was already daunting. She was a widow when we left Cuba. A lone woman with three kids making her way to a place she’d never been, to make a new life.

We lived in a small two-bedroom basement apartment in my uncle’s house. We were cramped, but thankful for all that we had. At least that’s what Mima kept saying. I felt different; the walls seemed to be getting closer to me each day. My brother and I shared a bunk-bed. I slept on the top bunk. Some nights I’d lie down, stared at the ceiling pressing down on me and cry myself to sleep. The more time passed the more isolated and lost I felt.

* * *

One day my Uncle came downstairs and asked me if I liked baseball. I said I did. He asked me if I knew Willie Mays, Willie McCovey or Juan Marichal. I didn’t know who they were. He went on to tell me all about how Mays was the world’s best center fielder and McCovey a great slugging first baseman and that Marichal’s delivery was a thing of beauty and made him a great pitcher. And that all of them were Giants. He made sure to tell me that from then on the Giants would be my team, and the Dodgers my hated rivals. I listened but felt no passion for any of it. I didn’t know the players, or the team.

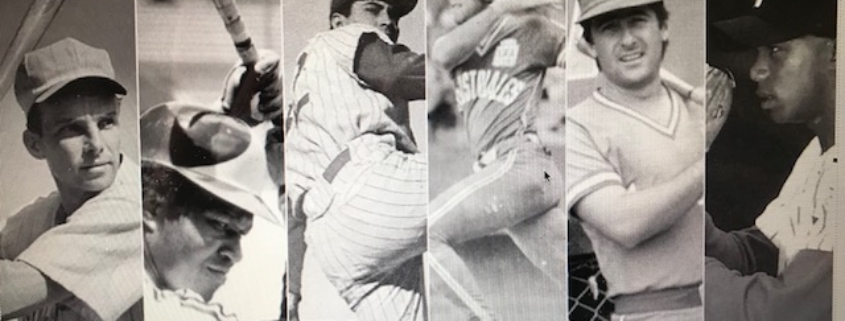

Six of Industriales’ most famous players: Pedro Chávez, Agustín Marquetti, Santiago “Changa” Mederos, Pedro Medina, Javier Méndez y Orlando “El Duke” Hernández. (Fotos Archivo de BdeC)

To me, Pedro Chavez was the world’s best first baseman, Tony Gonzalez the best ever shortstop and no one could ever hit Manuel Hurtado, my star pitcher. He had no idea who these guys were. He dismissed them. We argued and in the midst of that argument, I remembered home. But the memories were not external, or even in my mind’s eye, like a faded photograph; these memories came from someplace deeper, someplace that suddenly made my skin once again sense the caress of the breeze back home.

As I began to pick up a little bit of English, I would hide away at the school’s library, to read the San Francisco Chronicle’s Sports page. Back then it was called the “Green Sheet” because they printed it in a light green color and made it easy to find. Growing up in Cuba where politics came at you from all angles, the one thing I came to enjoy most about this newfound freedom was that I didn’t have to deal with it any longer. I could care less what was going on in the rest of the world. I went right to the box scores. Those were things I understood. You see in Cuba, you learn about such things as the infield-fly rule, balks, balls and strikes, well before you learn to read. In Havana, my friends and I would talk about how many hits Chavez got the night before or how many strike-outs Hurtado had, and then we’d argue about why Chavez took a fastball down the middle on a 3-2 count with two outs and men on base, or why Hurtado served up a slow curve in the sixth that resulted in a game tying home run for the opposing team.

I remember reading about the Miracle Mets, when they won the World Series in 1969. I began to recognize names: Earl Weaver, Tom Seaver, Boog Powell, Brooks Robinson. Following baseball pulled me away from my struggles to adapt; still, the names were unfamiliar and strange sounding.

* * *

That first Christmas, my uncle gave me a baseball glove. It was used, but it was the best gift I’d ever received. The glove was broken in, but not the way it should’ve been. I went on to dip the glove in water, put a ball in it and wrap a string around it. He watched me do that with a strange look on his face. I told him not to worry, that I knew what I was doing. Once the glove dried I slipped it under my mattress. I could feel the bump under my legs each night as I slept. It was like I was incubating the thing, waiting for it to hatch. After a week, I pulled it out from under the mattress and it was perfect, the pocket broken in just right. When I slid my fingers into the glove, I again sensed something that wasn’t a memory but more akin to seeing land after drifting for months in the open ocean.

Our house backed into the Sears parking lot, which was often empty in the summer nights after they closed. It was still light out and occasionally I’d see some kids running around playing baseball with a tennis ball. I drifted out there one afternoon, glove in hand and asked them if I could play. There were enough kids so that one guy batted and the others fielded. We took turns hitting and fielding. To them, it was just a game. But I was playing for my country, imagining myself as a member of the Cuban National team, playing against these Americanos. We would trade gloves each time one took the field while the other one batted. When it was over, I went to get my glove from the kid I’d lent it to. He was a bit taller than me. Instead of handing it back, he punched me in the eye and ran, glove still in hand. It was as though he’d taken home right out of my grasp. I chased the kid for three blocks until I caught up to him and smacked him in the back of the head. He fell and I snatched the glove from his hand. I was about to punch him again when he covered his head with his arms. I stopped short of hitting him and yelled the worst curse words and flurry of threats that I could muster. This was my glove. I’d been yanked from my home once and it would not happen again. He looked at me, not with fear, but with a furrowed brow. You see, all that yelling was in Spanish. I ran out of breath, and of words. Finally, I just screamed “Okay?” He nodded, and I walked home proud.

* * *

Later that summer, my uncle came down on a Saturday to tell my brother and I that we were going to a baseball game on Sunday, a double-header no less. It wasn’t to see Industriales, but I was nevertheless excited to see a real ballgame for the first time in my life. On Sunday my uncle his two sons, my brother and I drove to Candlestick Park on the South end of San Francisco. Years later that park would be derided as a “dump” of a stadium, but to me, on that day, it was a jewel. As I strolled in and through the tunnel, the green outfield and the manicured infield, with bright white bases perfectly aligned, unfolded before me like a colorful peacock tail. I stopped and thought of my childhood friends in Cuba. If they could only see this. Willie Mays patrolled center field for the Giants that day and I found out that Tito Fuentes, their second baseman, was Cuban. I became a Giants fan that day. Industriales were still a part of me, but it would be years before I’d be able to follow them again. And this place was now beginning to remind me of home. This language of baseball, I understood. It transcended borders. When I heard the first crack of the bat, it felt as though a new part of me, a new limb, reached out and touched the Havana I’d left behind.

* * *

My mother’s last birthday, with my brother, sister and me (on the right)

My mother died in October of 2014. That year, she watched just about every Giant’s game on TV. She loved Buster Posey, their catcher, because of his boyish looks and clutch hitting. She called me each day, sometimes at work, when they played back East and I wasn’t able to watch or listen, to give me updates of the score. She was our stalwart, our star, and our hero. Her death came in her sleep, as she’d hoped. My brother, my sister and I were devastated by losing her It was difficult to imagine life without her. Once again, I found myself forced to leave behind a time of my life that I’d never see again.

(Photo by Dilip Vishwanat/Getty Images)

We held a service for my mother, to celebrate her life. Family and friends gathered at my brother’s house after the service. By early afternoon, everyone had left. I, along with my brother, his partner, my sister, my kids and nephews, were left with the emptiness. On that same day, the Giants, in an impossible season reached the seventh game of the World Series against the Kansas City Royals.

We turned on the TV, to watch the game, but also to remember her. We watched Madison Baumgartner stroll out of the bullpen in the fifth inning, in a do or die game. Salvador Perez popped up in the ninth and Pablo Sandoval caught the final out, falling back to the ground and raising his arms in victory. We hugged and cried. We all wished she’d been able to see them win. Then we all agreed she probably helped them win. Whether she did or not we’ll never know.

Once again, baseball had given me the feeling of yet another limb reaching across time, across memories, across loss, to steady me and remind me that there are still a few more innings to play.

Jesus Francisco Sierra is currently working through a post MFA semester in Fiction at Antioch University Los Angeles. He emigrated from Cuba in 1969 and grew up in San Francisco’s Mission District. He still resides in the San Francisco Bay Area. Although he has been a lifelong writer and storyteller, he makes a living as a structural engineer. His inspiration, and his most supportive audience, are his adult daughter and son. He is fascinated by how transitions, both sought and imposed, have the power to either awaken or suppress the spirit. His work has previously been published in Marathon Literary Review and The Acentos Review.

Jesus Francisco Sierra is currently working through a post MFA semester in Fiction at Antioch University Los Angeles. He emigrated from Cuba in 1969 and grew up in San Francisco’s Mission District. He still resides in the San Francisco Bay Area. Although he has been a lifelong writer and storyteller, he makes a living as a structural engineer. His inspiration, and his most supportive audience, are his adult daughter and son. He is fascinated by how transitions, both sought and imposed, have the power to either awaken or suppress the spirit. His work has previously been published in Marathon Literary Review and The Acentos Review.