Orange is the New… Metamorphosis

Photo by Deanster1983 via Flickr.

In a town as small as this, I never imagined that I would sit so close to murder; knowing too well what happened without ever seeing it or hearing the details. Britany was dead and the police force had been pushed too far over the edge. It was as if this violent act of secrecy was a taunt that wouldn’t let up until justice was served and, somehow, between a car ride and a trashcan, I found myself caught in the middle of the investigation. At twenty, I should have been educated on how to avoid this road, but instead I dove into the forbidden territory, eyes as bright and wide as my eager grin, expecting my skull not to ricochet against the asphalt. When the rest of my graduating class was having the time of their lives, I was tangled so deep into the web that I became a cocoon of drugs, control, and misery. What kind of butterfly could possibly emerge out of that?

* * *

In 2011, I was arrested while taking out the trash. “I bet you wish you had talked now, huh?” The detective was smug while I sat cuffed and confused in his truck as he took me down to the police station. His question made me think that this was just a game to them: You help them do their job, and they’ll help you remain free, though then you’d have a target on your back. They wanted me to give them information on Britany’s murder. Britany was like me—involved with the same people, doing the same things I was. In fact, we’d taken a trip together once to pick up drugs for the others. The same detectives who had approached me had approached her, looking for information on the drug ring. According to court documents, she was supposed to meet them the next day, to let them know if she would cooperate or not—but she didn’t get that chance. Later that night, she was found dead in the front seat of her car, with the engine still running and her foot on the gas. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was two blocks away from the scene; I could see the police lights flashing in the dark distance as I fumbled with her murderer’s car keys, having been instructed to take his car to his house while he took mine on an errand.

How did I even get there?

* * *

I was a shy and awkward kid growing up, spending most of my time reading or writing or listening to music. I skipped the third grade and maintained straight A’s until the end of eighth grade when I just stopped caring. After that, I still managed to pass my classes and eventually graduated high school, but my home life was so contaminated with alcohol-fueled fights and dysfunction that I looked for ways to escape.

When I was sixteen, I did cocaine for the first time. I promised friends I wouldn’t do it again, but I could still taste the bittersweet drip in the back of my throat, and I knew I was in love. But I kept my word—mainly because I didn’t know how to get the stuff on my own.

Two years later, when I was eighteen, I met a woman, let’s say Michelle, through a mutual job. She was nine years older than me, and her loud and free personality intrigued me. She often came to the training sessions hungover, something she’d announce and then joke with the instructor about, but she’d still be so full of life. Eventually, I had a friend give her my number (shy and awkward, remember?) and, to my surprise, she used it.

Around the third or fourth time hanging out together, Michelle turned to me and asked, “Do you do powder?” After a very brief pause, I said, “Yes,” thinking about the first and only time I had done it and knowing I wanted to try it again. When she passed me the bag and a rolled-up dollar bill, I didn’t know what to do—the first time I’d done it was with some special gadget. She noticed my hesitation, laughed, and showed me how to take a bump.

This began a three-year tryst with a habit and a woman. It went from every other weekend to every few days, with the days between spent thinking about the next time.

My attachment to cocaine now coincided with my devotion to Michelle. I found myself doing everything she asked, and eventually everything she told me to do, as requests quickly turned into expectations. This is how I fell into my role of driving—trafficking drugs and money—for an “organization” led by Michelle and two of her exes.

* * *

In 2013, I was on pretrial release in Kansas for a federal drug charge. A year after the arrest, I’d pled guilty to one of two charges, “Conspiracy to Distribute 280 Grams or More of Crack Cocaine,” a Class A felony. Sentencing was pushed back every few months. My life was on pause.

My friends told me, “Oh, you’ll just get a slap on the wrist since it’s your first time.” They thought I’d be sentenced to probation. What they didn’t understand is that the U.S. Sentencing Commission didn’t allow a sentence of probation to be imposed for Class A felonies, even for a first offense. By taking a plea deal, I was looking at five years in prison. Without it, I was facing twenty years; ten years for each original charge.

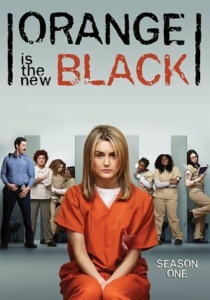

Promotional poster for Orange is the New Black

So, in the Summer of 2013, when Orange is the New Black (OITNB) first premiered on Netflix, I followed Piper’s narrative closely, asking myself, “Is that going to be me?”

* * *

OITNB tells the story of Piper Chapman, based on real-life Piper Kerman, who is sentenced to fifteen months in prison for an incident that occurred in her past. Ten years prior, she transported a suitcase full of drug money for her then-girlfriend, Alex Vause.

At the time of her arrest, Piper had moved on from that life. She was engaged and working as an executive in New York City. In the show, Piper and Alex are sent to the same prison facility where they rekindle their relationship.

Similarly, when I was arrested, Michelle and I had drifted apart. I had a new girlfriend and was no longer doing runs for the organization. But now I wondered if I’d be sent to the same prison as my ex, like Piper and Alex. I hoped so, because prison seemed like a scary and lonely place, and at least then I would know somebody, regardless of our sordid history.

* * *

In October 2014, I was finally set to be scheduled.

But more than a year before, in August 2013, the “Holder Memo” had been released as a guide for federal prosecutors. Issued by Attorney General Eric Holder, he instructed federal prosecutors not to specify drug quantities when charging nonviolent, low-level offenders, to avoid triggering mandatory minimum laws. The hope was to stop sentencing first-time drug offenders to prison time, which had been the norm up until then. It wasn’t a law, though. It was just a memo. The same memo that Jeff Sessions of the Trump administration rescinded, as easily as it had been issued.

Walking into the courtroom, it felt like I didn’t exist in the same dimension as everyone else. I could see and hear the people around me, but I didn’t feel like I was a part of it. I felt this way for three years, from the day I was arrested in August of 2011, until the day of my sentencing.

The judge came in and began. She went over my sentencing report—a detailed guide and point system which considers the crime along with any past criminal history and background in general, to formulate a recommended amount of time for me to serve. To my surprise, it also took into consideration juvenile history. My report included information on a brief stay in a psychiatric unit as a teenager, my adolescent mental health diagnoses, and a DUI I got when I was twenty-one. The judge went through all of this before giving her recommendation which, according to her report, was 144 months—or twelve years—in prison.

It was hard to process anything that she said after that. I was paralyzed, consumed by the fear of what was to come. I saw the judge looking at me, could hear her talking, but I couldn’t comprehend the words. Anxious dread overcame me as I wondered where I would be sent—the closest women’s prison being in Texas. I envisioned what it would be like to relinquish my freedom by walking through the heavy doors, into a place comprised of hardened unfamiliarity: concrete, metal, and people.

U.S. Court for the District of Kansas

I fell back into the present moment to hear the judge tell me her final sentence: “time-served.” Thanks to the Holder Memo, which was cited by the judge, this meant I had served my sentence already—forty-five days—the time I spent in jail after my initial arrest. Relief was instant, but so was shock. I’d spent the last three years knowing that I was going to be sent away, so it was difficult to grasp my freedom.

My co-defendant, the one who was equivalent to Alex Vause, wasn’t so lucky. She was sentenced to seven years, having taken a plea for a different charge attached to the murder—accessory after the fact. Even though we took pleas for different charges and we had different backgrounds, I can’t help but wonder if I might have been treated kinder because of the way I looked. I knew the story she told the detectives and I knew they didn’t believe her. I wondered if my skin had been a darker shade, like hers, if they wouldn’t have believed me either.

* * *

Despite feeling less and less like Piper as the series went on, the final season brought me full circle. Trying to navigate life after prison, life on probation, and life as a felon, she feels stifled by all of the rules and expectations laid out for her—as though she couldn’t possibly make the right decisions on her own, without paying a monthly fee to be “guided” by the federal probation system—I related to her. I remember the feeling when I was finally sentenced and officially a felon, a label that would follow me for the rest of my life.

My new probation officer came out for an initial home visit and the first thing she asked was, “Have you registered with the state of Kansas as a drug offender?”

“No, am I supposed to?”

Apparently, in Kansas, on top of reporting to my probation officer, I also had to report to the state in every county I was living in, employed in, and/or attending school in. I had fifteen days to report after being sentenced. If I didn’t, it would be considered a violation of the Kansas Offender Registration Act, which is a felony, which would then also be a violation of probation. Nobody told me how easy it was to accidentally violate probation.

I took time off work to go to the sheriff’s department in two different counties, paying a twenty-dollar registration fee. I sat silently and waited while they printed a confirmation for me to sign. Then I waited for them to take my picture, which was posted to an online public registry with my address and vehicle information for all to see. I did this every three months and was expected to do it for the next fifteen years. That would add up to $14,400 in total.

So when Piper was navigating life as a felon, I felt her struggle. When she was walking on eggshells at work to avoid letting her coworkers know her secret, I felt her struggle. When she lost her new group of mom-friends over being a felon, I felt her struggle. Every time I meet somebody new, I worry about them Googling me and never giving me a real chance because of what they might find. Not everyone is so accepting or understanding of mistakes that result in criminal convictions. Not everyone understands how the system is setup for us to fail.

* * *

When Piper’s pre-prison fiancé Larry told her that maybe it’s a good thing Alex named her, leading to Piper’s arrest, because it’s the most interesting thing about her—I really fucking felt that. Not because I’m thankful to have this conviction following me around, though I am thankful for parts of the outcome, but because sometimes I feel the same way about myself.

I often wonder how much more damage I would’ve done to my life if I hadn’t been named and if I hadn’t gotten arrested. I wonder if I hadn’t been involved in this huge ordeal, if I would have graduated to harder drugs, like heroin, which was something that intrigued me and that I’d contemplated trying in the past. Would I still be addicted now, maybe living on the streets? Or maybe I’d have overdosed, maybe I’d be dead by now, right?

Like final-season-Piper, I’ve learned a lot about how to carry myself and my label of felon. Every day, I’m learning how to forgive myself, even if society won’t. But, unlike Piper, I could never safely go back to any part of that life. I had to let that part go in order to create the space to grow.

* * *

Photo: Yahoo!

My arrest and conviction didn’t automatically rehabilitate me; I’d be lying if I said it did. I still have flashbacks sometimes when I take out the trash, I still get nervous when I see the police, and I’ve relapsed a few times since. But I no longer question what kind of butterfly can emerge from the chaotic cocoon I inhabited for so long. Instead, I am patient with myself, knowing that some butterflies take a little longer to break free, and some need help to spread their wings.

Alisha Escobedo is a marketing coordinator and an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. She is also Proof Edit Manager for Lunch Ticket. Her work can be found in Desolate Country: We the Poets, United, Against Trump and Prompts!: A Spontaneous Anthology. She currently resides in Long Beach, CA.