Alexander Chee, Author

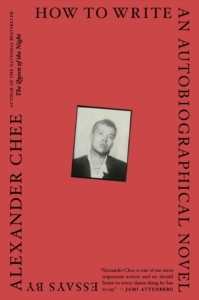

Alexander Chee is the best-selling author of the novels The Queen of the Night and Edinburgh. His essay collection How to Write an Autobiographical Novel made Entertainment Weekly’s list of the top nonfiction books of the past decade, and Rebecca Solnit selected the essay, “The Autobiography of My Novel,” for inclusion in The Best American Essays 2019. Chee is a contributing editor at The New Republic and an editor at large at the Virginia Quarterly Review. His work has appeared in The Best American Essays 2016, the New York Times Magazine, Slate, Guernica, and Tin House, among others. He is an associate professor of English at Dartmouth College.

Alexander Chee is the best-selling author of the novels The Queen of the Night and Edinburgh. His essay collection How to Write an Autobiographical Novel made Entertainment Weekly’s list of the top nonfiction books of the past decade, and Rebecca Solnit selected the essay, “The Autobiography of My Novel,” for inclusion in The Best American Essays 2019. Chee is a contributing editor at The New Republic and an editor at large at the Virginia Quarterly Review. His work has appeared in The Best American Essays 2016, the New York Times Magazine, Slate, Guernica, and Tin House, among others. He is an associate professor of English at Dartmouth College.

Antioch University’s MFA community was fortunate to have Alexander Chee as a guest at our December 2019 residency. In his fiction seminar, Chee applied his “point of telling” frame to James Baldwin’s masterpiece, Go Tell It on the Mountain. While examining the structure of the novel through Baldwin’s point-of-view choices, Chee drew upon other famous literary works and even mentioned the pivotal deaths in The Great Gatsby and Moby-Dick. To audience cries of, “Spoiler alert!” Chee joked, “If you haven’t read these books, I’m sorry, I don’t know how to help you.”

The same holds true for Chee’s work: If you’re a writer and you haven’t read his novels or essays, I don’t know how to help you either. On a rainy LA evening, over gin drinks in his hotel bar, Alexander Chee and I discussed, among other topics, the novel he teaches the most, the difference between basic and narrative description, and what writers should never do to their agents.

Michael Sellar: You write about your own MFA experience at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in your essay collection—in particular, the workshops led by Deborah Eisenberg. How do you run your own workshops?

Alexander Chee: The way I understand a workshop is as a mirror to the writer, holding up a mirror to what they’ve written—such that they can see it. That sort of experience of having the work kind of vanish in front of your eyes because you’ve been working on it so long. I try to get them to re-experience what they’ve written through the experience of the readers. I try to get the class to think about that as a way of helping the writer.

MS: The quote that startled me from your reading last night was: “Many student writers become obsessed with aesthetics.” How do you get your students to say what they need to say on the page?

AC: You try to meet them where they are and not try to get them to some sort of standardized place. I really have, in recent times, focused a lot on getting students to resist trying to standardize a particular piece of fiction. Rather than have someone say something like, “I just don’t believe a mother would talk like that.” Instead I say, “Can you instead ask it another way? Can you say, ‘Why is this mother talking like this?’” If you feel there’s not enough support for whatever is happening in the text, can you ask for that, instead of rendering some sort of withering judgment. I try to get them to move off that attempt to make everything sanded down and normal, which is a strange thing that can happen.

MS: How do you lead students toward convincing detail—“the spark of life”—within their fiction?

AC: I think that most of what we see in writing is impressionism in the service of realism. And that people don’t know that that’s what they’re doing. They just think that’s what they’re supposed to do, so they haven’t really thought about how that works out. There’s this belief that if you apply enough technique in all these different ways, that you will end up with a novel. Technique is not everything. There’s a lot to recommend it, but the spark of life is something that the reader feels through the writer, and the writer has to feel it first.

It’s kind of like you’re building a ship in a bottle, but the bottle is the reader’s mind and the ship is the story.

MS: It reminds me of what you wrote about in your final essay, “On Becoming an American Writer,” where the writer’s and the reader’s memory commingle.

AC: It’s kind of like you’re building a ship in a bottle, but the bottle is the reader’s mind and the ship is the story. The only way that that can happen is if they read something and they get it out of what they’ve read from you.

I did have a student recently ask, “How do you describe things?” I said to her that it depends on what you want to achieve, but the idea is that you’re trying to evoke the story as well as describe the story. You’re thinking about: what are the subtle influences and what are the significant ones? I talk to my students a lot about what I think of as “the theater of the event.” How much do you think the theater of the event affects what’s in it?

Think of description as the unspoken music of the story, the details that signal the context clues that the characters are responding to. By describing them, the reader can use them to construct not just the story, but also how they feel about it, and the story is evoked for them as well. As an example, if I tell you, She was angry, that’s basic. If I tell you, She would not meet his eyes, acting instead as if he were not there, as if the room were empty, and then she left without saying good-bye, that’s narrative description. That tells you something very specific about her anger. That’s also describing something as the story is happening, so that both the story’s described as well as the character. That’s what I mean by narrative description.

MS: You have said that Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go is the novel you taught maybe more than any other piece of fiction in your teaching career. What is it about this novel for you to teach it so often?

AC: That’s a good question. It’s an immensely teachable novel and it’s a really easy novel to teach in several different ways, when you’re trying to teach the retrospective novel in particular. It makes use of the “I” narrator and “I” character divide that I was talking about in my seminar, where there’s a narrator who is very clearly telling you a story from a particular place in their life.

MS: What you have called “the extraordinary time of the character”?

AC: Right. When you reach the ending, you realize that the novel began just somewhere passed that for this narrator, that she was moved after that to begin the writing of this. For the casual reader of this interview, the novel is about clones who are being raised for replacement parts. The novel is so peculiarly the product of her mind, the narrator’s mind, in the way that it’s written. Ishiguro has done this really tremendous aesthetic act of creating something that is by someone who was raised to surrender herself to the status quo again and again and again. It has this uncanny aspect where it feels like Victorian novels that you’ve encountered and yet there’s never a mention of parents, there’s never a family, and gradually you learn why. It’s a really provocative novel in any number of ways as a result.

MS: I’m sure it depends on the course, but what other books, like Ishiguro’s and Baldwin’s, do you love to teach?

AC: I teach Autobiography of Red by Anne Carson, Sula by Toni Morrison, and Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Gabriel García Márquez. This year (2019), I taught Friday Black and Her Body and Other Parties. I think Francine Prose’s Reading Like a Writer is an excellent textbook for an intro class to get them to think about reading for technique and starting conversations about what exactly those techniques would even be. I often teach Charles Baxter’s Burning Down the House for intermediate or advanced classes.

MS: Selfishly, I wanted to ask you about one of your heroes, Joy Williams. I was wondering if you have ever taught any of her work.

AC: I teach one of her stories, “The Blue Men,” a great deal.

MS: I love “The Blue Men.” What is it about Williams that attracts you to her writing?

AC: I think what I like about her is that her work reveals how uncanny the world is all on its own without any ghosts at all [laughs], how uncanny the experience of being alive is. Sometimes there are ghosts in her work. She really pays attention to also the way money works in the world in a way that I appreciate, and she really pays attention to the transactional nature of so many people’s relationships as well.

MS: And her dark humor is certainly on display in “The Blue Men.”

AC: The moment I remember so much from that story is where the mother is standing and discovers a blueberry muffin in her hand that she doesn’t remember picking up. [Laughs.] And she’s looking at it and the line is like, “Muffins like this had tricked her before” or something. It’s not really the line, but it’s something like that.

MS: Your second novel, The Queen of the Night, took fifteen years, on-and-off, to complete. Did you have any tricks or tools to see you through?

AC: (With deadpan comic timing, Chee points a finger at his gin martini.)

MS: [Laughs] Say no more!

AC: [Laughs] You know you’re human. I think one thing I regret is that I treated the success of Edinburgh as if it were a fluke. But it was not a fluke. I worked very hard. I did something very complicated and pulled it off. Treating it as a fluke meant that I didn’t give myself credit for it. What I did for myself emotionally was, I said, “Well, you’ll be a real writer when you finish that second novel.” So I pushed the goal posts.

MS: You talked about how people had said you were talented when you were first starting out.

AC: Right.

MS: But you didn’t put any stock in that. Then you do work hard, only to push the goal posts.

AC: It might just be growing up in a state that was so heavily influenced by Calvinism, like Maine. I thought about it when I read Elizabeth Strout’s profile in The New Yorker and the writer went to see Strout’s mother and asked her how she felt about her daughter winning the Pulitzer and her mom said, “I was very proud of her not cheating.” [Laughs] That is the most Maine thing ever. It’s a state that constantly asks you to tear yourself down in advance of anybody else who might. A lot of writers after their first novel is published, especially if it wins any prizes or gets significant review attention, feel embarrassed to have done well. It’s not the same as humility. But we’re asked to believe that it is and so we perform it sometimes at our own expense with this idea that it’s humility and it’s not. It’s self-abnegation, which is different.

MS: With The Queen of the Night, how did you avoid “research rapture”? Did you succumb to it at times?

AC: The problem with historical fiction really is that there are times at which it has neither the pleasures of biography nor the pleasures of fiction writing for the writer. You’re writing along and suddenly you realize your character hasn’t eaten for days in front of the reader. What would they be eating?

MS: I think you joked that your character couldn’t even sneeze without you heading off to the research library.

AC: At one point, yeah. I was haunted by The New York Times review that I had seen so often of historical fiction, where the writer was some kind of historian and would sort of rip apart what someone had written because they had gotten this fact or that fact wrong. Instead, what I got were these sort of acid, backhanded compliments: “It’s so well researched.” “It’s like copiously researched.” And what I realized was that they were always going to complain about something. There was never going to be a real win.

The answer to the question though, about the rapture, is, yes, that definitely is the case. In fact, I remember when I was finishing the novel, after I had pulled it in 2013 and wanted to go back and redo certain aspects. I was finishing it again a year later and I went to Austin, TX, as their visiting writer and my office had a view of the entrance of the Ransom Center. I told my editor this and she said, “I absolutely forbid you from going in there. You are not allowed—not allowed—to go in there.”

MS: Congratulations again on all of the success with How to Write an Autobiographical Novel. I’m sure every essay had its own challenges, but was there one in particular that was hardest for you to write?

AC: Probably “The Guardians” was the hardest. It felt like looking at something that was only visible out of the corner of your eye, and when you tried to look at it directly, it went away. The lesson that I learned from these essays about form was that whatever the problem was that felt like it made the essay impossible to finish, or even to write, you make that the structure. [Laughs] Rather than feel like “Ah, I’m so embarrassed,” instead you’re like, “Okay, this is just the nature of the problem.”

MS: One of the essays that surprised and delighted me was “The Rosary,” about your growing a rose garden in Brooklyn. Toward the end of that essay, you share a powerful personal insight: “The lesson for me at least—and this I think of as the gift of the garden, learned every year I lived in that apartment: you can lose more than you thought possible and still grow back, stronger than anyone imagined.” I would be tempted to end the essay there, but instead you push onward into even deeper personal terrain, exploring themes of self-abandonment, self-reckoning, and promise or dream of self. How do you know when a piece is finished?

AC: It’s really about exploring a topic. For that essay, the structure is: this is when I began the garden and this is when I left the apartment. So that ends up becoming the default structure. And that sometimes is the easiest to rely on when everything else can seem so hard to wrangle. Sometimes you just go back to the old basics because they work. You still have to find a way to bring it ringing down. One thing that I try to do is I try to reveal a last shape, as it were, to the whole. I think when I was ending that essay, I was thinking about something that’s called “the ending passed the ending,” which is, years later, I have a student who has a view of the garden. He asked me if I wanted to come see it and I’ve never been to his apartment to do that. I could have. I may still someday. Maybe I’ll write an essay about that when I do. [Laughs]

MS: What guidance would you give young writers who are looking for an agent? What are the important things to bear in mind in that relationship?

AC: I think you should wait until you have a book that’s finished. I think that it might be tempting to try to sign up with an agent before then, but I think it’s a mistake. You need to be able to finish the book on your own, so that you have the full sense of it belonging to you before you go out on the market with it. The reason for that is that you can get so caught up in the acceptance that an agent might represent to you—like having one—that you unconsciously or consciously give away some of your power over your sense of what matters in the manuscript and you really need that to save yourself when you are writing. And you’ll need that over the course of your whole career.

It’s good to think about what you want for yourself five years, ten years, down the road. Ask yourself if the agent will go in those directions. Some common problems that I see my friends have are that they have an agent who they signed up with in relationship to, say, a creative nonfiction project, but suddenly they’ve written a novel and the agent doesn’t handle fiction and they feel stranded. Try to be as honest with yourself as possible about where you think you might want to go and what sort of boundaries you’re willing to accept. Is there a plan in place in case you go in a different direction? Can they refer you to another agent at the agency who can represent you on that project, or would you need to find new representation? That would be a real problem.

My biggest advice I have about agents is just not to surprise them. You don’t want your editor to be calling them with a surprise and you don’t want to be calling them with a surprise about what you said to your editor. If you’re angry about something, talk to them first, especially.

MS: In preparing for this interview, I listened to a podcast where you recounted hanging out with Deborah Eisenberg, Denis Johnson, and Margaret Atwood while at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Now, when I speak about my own MFA experience, I’ll be able to say I got to spend some time with Alexander Chee. What an honor and a privilege.

AC: Thank you very much.

From early childhood to his work as a former literary agent and executive at The New Yorker and Vanity Fair, Michael Sellar has been an inveterate reader. Now, as an MFA candidate at Antioch University, he writes his own stories while raising a toddler with wife Jennifer in Santa Monica, CA. Follow him on Twitter @mdsellar.