On Writing, Politics, and Imposter Syndrome: An Interview with Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman

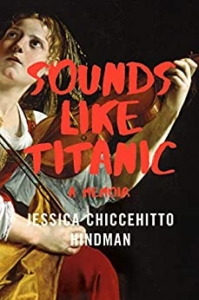

Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman wanted to be a professional violinist when she was a child, and in a way she kind of got her wish. Sounds Like Titanic: A Memoir, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and named a Best Book of 2019 by Amazon, details Hindman’s life as the violinist in an orchestra whose performances pantomimed playing instruments to recorded music. Music that, yes, sounded vaguely like the soundtrack to Titanic. Hindman’s memoir recounts her time traveling with the orchestra in the early 2000s, a time of political turmoil that resonates with the early 2020s.

Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman wanted to be a professional violinist when she was a child, and in a way she kind of got her wish. Sounds Like Titanic: A Memoir, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and named a Best Book of 2019 by Amazon, details Hindman’s life as the violinist in an orchestra whose performances pantomimed playing instruments to recorded music. Music that, yes, sounded vaguely like the soundtrack to Titanic. Hindman’s memoir recounts her time traveling with the orchestra in the early 2000s, a time of political turmoil that resonates with the early 2020s.

Now an Associate Professor of English at Northern Kentucky University, Jessica was kind enough to discuss writing, politics, and imposter syndrome with Lunch Ticket.

Erica Colón: In your writing, you switch point of view and use lists, and other creative methods to tell your story. How do you define creative nonfiction as a type of creative writing?

Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman: Thank you for saying that. You know, it’s so funny. I teach almost all creative-nonfiction classes and to me it is absolutely in the realm of poetry and fiction, not technical writing. However, we spend a lot of time in intro classes discussing exactly this question. What is creative nonfiction? Since my job is as a creative-nonfiction professor I have to have an elevator answer for that question. If I’m stuck in the elevator with administrators of the university, or the president of the university, and they ask, what do you do here? I tell them I teach creative nonfiction. What is that? I have to answer really quickly so that I keep my job, right? And so my answer is that it’s any form of writing that uses poetry and fiction to write, but then stays within the realm of the truth. If I have another minute on the elevator, I might talk about how the restrictions of the truth are not as restricting as one might imagine. I always teach the same intro class to creative writing. I begin with poetry, and then I go into fiction, and then we end with creative nonfiction. The reason for that is because I don’t think you can write creative nonfiction without poetry and fiction. To me, it’s evolved out of those things. Yes, we have the one restriction that it has to be based on truth and within the realm of the factual, but it’s using those techniques of poetry and fiction. If it’s not, it’s something else. It might be reporting or technical writing or something. It is the poetry and fiction part that make it creative nonfiction. I find that once students realize what creative nonfiction is, everyone’s so excited about it.

I always teach the same intro class to creative writing. I begin with poetry, and then I go into fiction, and then we end with creative nonfiction. The reason for that is because I don’t think you can write creative nonfiction without poetry and fiction. To me, it’s evolved out of those things.

EC: When I talk about writing creative nonfiction, people say they never do anything, and then I end up hearing from them later that they grew up in an RV and the only activity they did for fun was dig five-foot holes. What do you think makes a personal experience worth writing about? Is it about the events, the characters, or maybe just like the self-reflection looking back at it?

JCH: I would say all of the above. The only thing I’d add is if the writer is curious about it. If the basis is interesting to you the writer, then it can be interesting to the reader. If it’s not interesting to you, then you can’t force someone to be interested in your own life. But I think often people say things like, oh I have nothing interesting to write about, because they haven’t been exposed to other writers who are writing about similar experiences. What I love about personal narrative is that often I come across the same experiences over and over again. As you can imagine, there’s certain things that happen to a lot of people who have various backgrounds. People’s parents get divorced. People suffer with addiction, with romantic breakups, or with coming out, all sorts of things. These stories are familiar. We’ve read them many times. What makes them totally unique every time is the writer’s own voice and approach. That’s what I love about my job as a teacher; I really see myself as there to help each person sound more like themselves so that, yes, you can write the 3,000th memoir about alcohol addiction. There’s a million of them, but none of them are going to be like yours. You’re going to sound so like you that no one else is going to. Now, of course, in an intro class a lot of things will sound cliché. I think that sometimes grumpy old professors say they don’t want any personal narratives about breakups as if some of our greatest literature isn’t about people’s breakups. What they’re really responding to is just that all of us in our early writing sound like each other. But if you go on and become more advanced, you sound more and more like yourself. By the end of the process of writing that memoir, I was like, oh, here I am! I’m right here on the page. I’ve been looking for myself.

EC: I appreciated the note at the beginning of Sounds Like Titanic that discusses the idea that memory is inconsistent. Now that you’ve published your memoir, do you view any of the written events kind of in a new light?

JCH: Not in a factual way. Myself, my editors, agent, and everybody who helped with the book really went over and over again, to be as truthful as possible. I don’t think anything’s really changed on that front, but what I will say is that if I was writing the book now I would probably write it completely differently. And that’s what makes memoir so interesting. By May of 2013, the first draft was out, so I was thirty-two. About seven years have gone by and even in that seven years my life changed so much. I’m way less angry now than I was writing that book. I mean, I didn’t think I was going to get a job after my PhD. I was furious at the whole system, and I was just like, fuck it, really, I am going to write this book because it doesn’t matter anymore. Nothing matters. I’ve wasted all this time in grad school. I have all the student debt. I’m just going to write furiously because I am furious. As it ended up, I got some lucky, lucky breaks in life. There was a lot of privilege, but also hard work. So things have worked out way better than they looked like they were going to work out back in 2013 for me. I got a job. I found a wonderful person who I got married to. We’re starting a family. These are things that I just couldn’t even imagine happening even a few years ago. Nowadays, I actually think it’s a big problem with my writing. I’m just not very mad. I’m pretty happy, so writing is harder!

JCH: Not in a factual way. Myself, my editors, agent, and everybody who helped with the book really went over and over again, to be as truthful as possible. I don’t think anything’s really changed on that front, but what I will say is that if I was writing the book now I would probably write it completely differently. And that’s what makes memoir so interesting. By May of 2013, the first draft was out, so I was thirty-two. About seven years have gone by and even in that seven years my life changed so much. I’m way less angry now than I was writing that book. I mean, I didn’t think I was going to get a job after my PhD. I was furious at the whole system, and I was just like, fuck it, really, I am going to write this book because it doesn’t matter anymore. Nothing matters. I’ve wasted all this time in grad school. I have all the student debt. I’m just going to write furiously because I am furious. As it ended up, I got some lucky, lucky breaks in life. There was a lot of privilege, but also hard work. So things have worked out way better than they looked like they were going to work out back in 2013 for me. I got a job. I found a wonderful person who I got married to. We’re starting a family. These are things that I just couldn’t even imagine happening even a few years ago. Nowadays, I actually think it’s a big problem with my writing. I’m just not very mad. I’m pretty happy, so writing is harder!

EC: I’ve seen a lot of people whining on the internet about the choice to keep The Composer as an anonymous figure in the book. I know you’ve mentioned before that this book was never supposed to be an exposé on him. When in your writing process did you make the decision not to out him and kind of keep him as a more mysterious figure?

JCH: That kind of came in phases. I always knew that the book was not going to be an exposé—or I shouldn’t say always, but from pretty early on. Early in the drafting process, I was like, no, this is about way bigger things. But I was using his real name in drafts pretty late in the process, because when I was sending it out to agents and editors I was afraid no one would believe me. I thought if I use this real name they could just look him up and look at the things that are online. I didn’t know how agents, editors, or lawyers, would react. I just kind of kept it with his real name until my agent, Allison Devereux suggested it’s not only legally better but more compelling to keep his name out. That felt like the right choice once we did it. I was the one who came up with “The Composer” because I realized that the whole arc of the book is me realizing that I actually have a lot in common with him. So many of his bad traits are my bad traits as well. He writes music, and I write books. What I love about the term “The Composer” is that it works both ways. You could be a musical composer but we also talk about writing composition. I love that name, because it kind of reflects back on me too.

EC: Absolutely. I think by giving the exact name of The Composer it would take away from the narrative because it would put too much focus on him. I was surprised to see so many people were mad about it.

JCH: Yeah, and it’s not like it’s some huge secret you couldn’t know. It’s out there if people want to find it on the internet. I’m so glad we made this decision for so many reasons, and one is just how the internet works. You say someone’s name and then like a million people pile on them and whatever his faults are maybe he does not deserve like an internet mob. The “crimes” weren’t that high, so I did not want this to affect his business or his performances. In creative nonfiction, changing names essentially allows someone else to tell their own story. You’re not necessarily telling their story. This is your memory of them. You kind of reserve that right for them to talk about themselves. Maybe it would not look the same as what you know.

In creative nonfiction, changing names essentially allows someone else to tell their own story. You’re not necessarily telling their story. This is your memory of them. You kind of reserve that right for them to talk about themselves. Maybe it would not look the same as what you know.

EC: Have you talked to any of the coworkers you may have written about since the release of your memoir? Have any of them reached out to you?

JCH: Actually, even a little bit before that. I began writing this in the fall of 2005 and I had not talked to anyone during that period. All that writing up to 2013, when I finished the first draft, and then I was still working on it up until fall of 2018, when we were doing the last edits. So that’s thirteen years since it happened, and in that time I had not talked to any of the people named in the book. Then, right before the book came out, I had to get permission from the character I call Yevgeny, the Russian violinist, because I was printing his email when he says he quits and he can’t take it anymore. Even if you’re just publishing a little snippet of an email, you have to get legal permission from the person to use their written work. So you can imagine how this goes for me. It’s like, this guy is a really huge figure in my life and yet I have not talked to him in over ten years. I didn’t even have his email. I didn’t have his phone number. First, it took me a while to even find him. Then when I did, I sent him an email that was like, oh, remember me? I’ve written a book about this job we used to have together. By the way, you’re a major character in it and also could you sign this legal form? He very wisely asked if he could read the book first and so I sent him the PDF of it. He read it in just a few hours and got back to me right away, and said it was exactly like this. That was such a relief, because his opinion is probably, apart from my family, the most important to me. I have also heard from a few musicians who I actually did not work with but who did work for The Composer at other times in his career, and they all just kind of said, oh yeah, this rings a bell. Things have been pretty positive, so that’s good to hear.

EC: You’ve spoken before about the role politics and the George W. Bush presidency played in your life. The time that the book was released also coincided with more political turmoil. Essentially, the entire time you’ve been writing this book has been very strange politically. Did that play any hand in why you decided to tell your story? Did it inform your view of the situation in any way?

JCH: I think it informed the reception of the book. Obviously, when I started writing about reality versus fakery in the mid-2000s I did not know that then that was going to lead up to Donald Trump. I finished the manuscript in May of 2013. I think that after the 2016 election the book took on this meaning for people. There’re so many routes to the situation we’ve been in. You can trace it back to the very beginnings of this country, based on racism and genocide. So I’m not saying that the mid-2000s is when everything horrible started, but I do think there’s something very specific about the way we talk about truth and reality that is rooted in the early 2000s, with the rise of reality TV, which of course I write about. Donald Trump was a reality TV star. I think that the Iraq war politically was a moment in which TV gained the ability to flat-out lie and have everybody know and go along with it. At least in my lifetime that was an apex of that sort of fakery that then set up things for ten years later to be even more ridiculous. It’s unfortunate. I told people before, I would much rather our country be in better shape than my book, be more relevant, but here we are so…small silver lining. At least the book is more relevant.

EC: The last question I have is: does any creative person ever stop having imposter syndrome?

JCH: Imposter syndrome is something that people’s understanding of has shifted on a bit since the book came out. It’s a term that is much more widespread than it was when I was first drafting. I think now that we have so many more widespread conversations about structural inequalities, I would write that section a little bit differently. Because, in some ways, when writing I was thinking of imposter syndrome as an individual failing of my own. Like, why can’t I just believe in myself? I would be able to do these things that I’m not able to do if I did. But, really, why did I think that in the first place? I came in through a series of life experiences that were connected to my gender. That feeling that I could not achieve was connected to sexism and misogyny. On the other hand, people of color and people who are marginalized in worse ways than I am often have imposter syndrome worse than I do. If you’re feeling like you can’t do it, it might be because the world has literally made it so that you can’t do it. So I would add on to what I wrote, to say: yes, there are internalized insecurities, but let’s not disconnect that from what the world has told you about yourself and what the real realities are in terms of what you can do and what you can’t in a society with no jobs, huge student loan debt, huge structural inequalities, rural and geographic inequalities which are sometimes left out of conversations about structural inequality. Those things are real. They’re not made up all in your head because you’re a crazy lady. It is often not just your perceptions, but the reality that those barriers are in front of you.

Erica Colón is an Antioch University Los Angeles MFA in creative writing candidate who writes all the time and reads at least three times as much. They have volunteered with the literary magazines Blue Mesa Review and Lunch Ticket, as well as many different non-profits. An avid re-reader and re-watcher, Erica has no shame in how many hours they’ve put into consuming the same content repeatedly. If you enjoy sporadically posted pictures of books and low effort captions, check out their Bookstagram at www.instagram.com/ReinaTellsTales