Bershert

Each night, I fall through time and space online, a plunge that drops me into myself, too, down through my own veins and bones, into the space my DNA curls around. Each night, I fall toward my ancestors.

I was scrolling through Instagram several months ago when a post by the brilliant writer Myriam Gurba knocked my hand off my phone. Two Latinx women stared out from a Victorian-era photo in dark lace dresses—a small, older woman sitting, a young woman standing beside her, a protective hand on the elder woman’s shoulder. Gurba had captioned the photo, “Which ancestors do you appeal to for guidance? I appeal to those who were revolutionary in thought and deed.”

The only grandparent alive when I was born, my dad’s mother, died when I was six, and my parents, both gone now, too, didn’t speak much about their own parents or those who came before. I read Gurba’s words over and over again. I had no idea which ancestors I could appeal to for guidance, no idea which were revolutionary in thought and deed.

The prospect of connecting with my roots was deeply appealing, deeply grounding, after months of what felt like floating around inside a quarantine space station. If I couldn’t hug my grown kids or siblings scattered across North America, maybe I could embrace the family tree that held us all together, feel the heft of branches that had seemed wispy as ghosts.

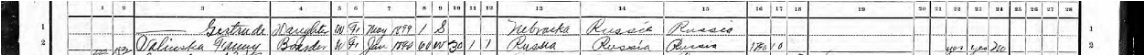

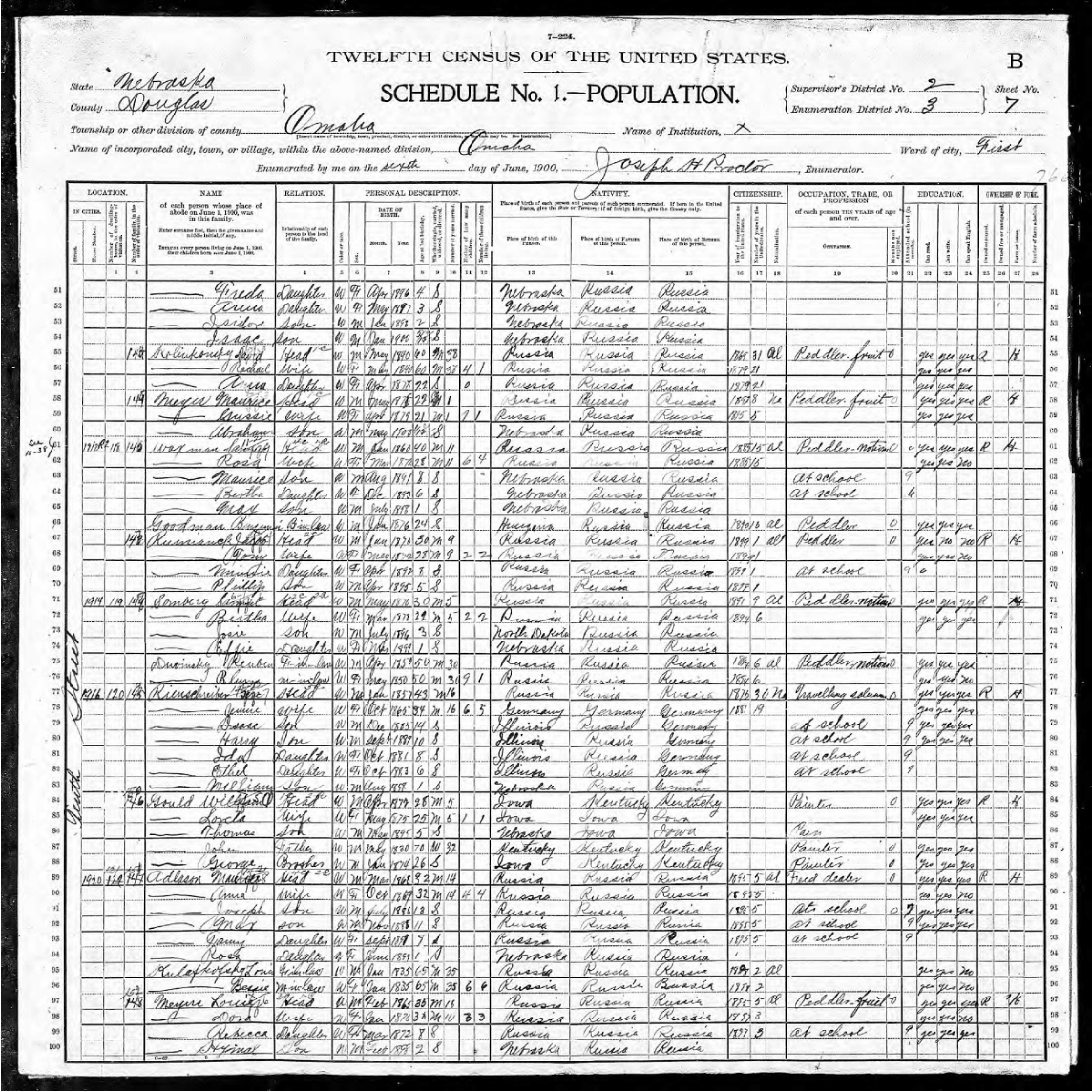

My mom, who had a delusional disorder that often put her on an alternate timeline, was not the most reliable narrator, so I questioned the veracity of the few ancestral stories she had told me. After her death, my sister and I asked our aunt, our mom’s estranged sister, about a horrific story our mom had shared about her father witnessing Cossacks rape and murder his pregnant mother. Our aunt shook her head and said “I don’t know about that.” I typed my grandfather’s name into FamilySearch.org to try to suss out the truth of his past, but couldn’t find anything prior to him marrying my grandmother Gertrude in 1917. I searched for Gertrude next, using her maiden name, Meyers, and a census popped up from 1900, when she was a year old in Omaha, Nebraska. Her parents, I learned, were Louis, a fruit peddler who came to America from Russia in 1893, and Dora, who followed him to America in 1897. He could speak English in 1900; she could not. Their daughter, Rebecca (who I had met as “Aunt Becky” a few times as a child), was born in Russia in 1892 and had sailed to America with Dora to join a father she likely didn’t remember. Their son Hyman was born in Nebraska in 1898.

Learning my great grandparents’ names, learning my great grandfather sold fruit (another obsession of mine) made that branch of the family tree not only come into sharper focus, but

burst forth with apples. Further searching on the site yielded nothing else about the Meyers family, so I turned to the free offerings at Ancestry.com, then quickly splurged on a membership,

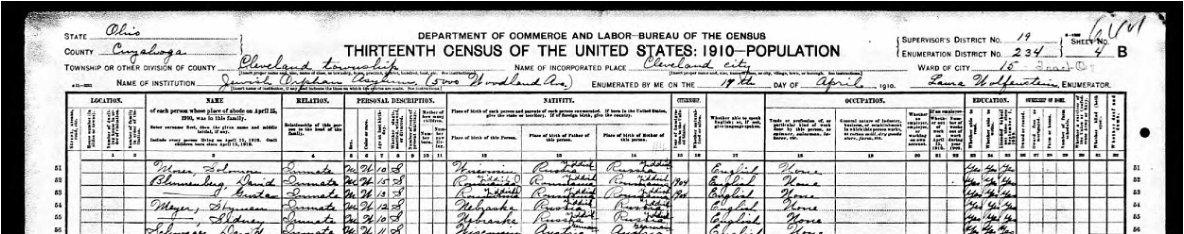

aching to see what lay beyond the paywall. My mom had told me her uncles had been sent to an orphanage after their mother entered a TB sanitarium, and an aunt and uncle would only take in the two girls. I discovered this was indeed true; Hyman and Sidney (born in 1900) were sent to the Jewish Orphan Asylum in Cleveland, Ohio, where they were heartbreakingly listed as “inmates” in the 1910 census.

A Google Search led me to a review of the book Inside Looking Out: The Cleveland Jewish Orphan Asylum, 1868-1924 by Gary Edward Polster, and later to reading the book, itself, where I learned the orphanage privileged German Jews over Russian Jews, and stripped Yiddish from all the Russian Jewish children there, some of whom couldn’t understand their families when they were later reunited.

The mother tongue that had been wrenched from my great uncles, that had faded from the rest of my family’s mouths as they assimilated into American life, into whiteness, was recently added to Duolingo. I now study Yiddish on my phone, excited to learn words like געשמאַק (pronounced “geshmak”) for “delicious,” words that feel delicious in my mouth, words that feel like home.

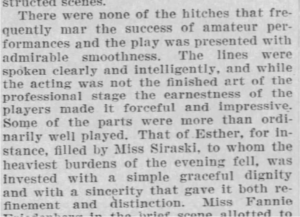

I fall again and again into Ancestry.com, where I live for the little leaf icon that tells me there’s a new hint for my family tree, and FindAGrave.com, where, amongst other discoveries, a great uncle I hadn’t known about stares out intensely from a ceramic photo on his headstone, and Newspapers.com, where, amidst other gems, I read an article from 1905 about my dad’s mom starring as Queen Esther in a Purim play in Baltimore, and the History of Jewish Communities in Ukrainesite, where I continue to learn about the shtetls some of my ancestors fled from…all these sites, and the sites they point me toward for further research, help me access the trauma and humor and story spun into my cells.

I don’t know where this plunge is taking me, whether it will lead to a bigger writing project, or simply a deeper understanding of where I come from, but I’m trusting the process, letting it pull me into its fathoms. When I started this journey, I knew I was daughter of Arlene and Buzz, granddaughter of Molly, Simon, Gertrude, and Benjamin. Now I know I’m great granddaughter of Dora, Louis, Sybil, Hyman, Sarah, Joseph, Jacob, and Esther Rifka, great great granddaughter of Aaron and Sarah and others whose names I hope to learn. I know who I can appeal to now, and sometimes it feels they’re calling to me, in turn.

I’m not religious but recently decided to light weekly Shabbos candles as an embodied means of connection, saying the same blessings Sarah and Esther Rifka and the rest chanted each Friday night, sweeping our hands over the flame in shared choreography across time. The day I voiced this desire to my spouse, lamenting the fact that I had forgotten to take the Shabbos candlesticks my orthodox cousins had given me upon my first wedding when I left that marriage thirteen years ago, my daughter, who was cleaning out her dad’s shed, texted me a picture of those very candlesticks, writing “Do these mean anything to you?” My whole body broke into gooseflesh. The candlesticks are silver, twisted like DNA; they’re in a box lined with velvet red as blood. My ancestors whispering “bershert”, Yiddish for “inevitable”; my ancestors lighting the way for my fall, for my return.

Gayle Brandeis is the author, most recently, of the memoir The Art of Misdiagnosis (Beacon Press), and the novel in poems, Many Restless Concerns (Black Lawrence Press), shortlisted for the Shirley Jackson Award. Earlier books include the poetry collection The Selfless Bliss of the Body (Finishing Line Press), the craft book Fruitflesh: Seeds of Inspiration for Women Who Write (HarperOne) and the novels The Book of Dead Birds (HarperCollins), which won the PEN/Bellwether Prize judged by Barbara Kingsolver, Toni Morrison, and Maxine Hong Kingston, Self Storage (Ballantine), Delta Girls (Ballantine), and My Life with the Lincolns (Henry Holt BYR), chosen as a state-wide read in Wisconsin. Her essay collection Drawing/Breath will be released by Overcup Press in 2023. Gayle’s essays, poetry, and short fiction have been widely published in places such as The Guardian, The New York Times, The Washington Post, O (The Oprah Magazine), The Rumpus, Salon, and more, and have received numerous honors, including the Columbia Journal Nonfiction Award, a Barbara Mandigo Kelly Peace Poetry Award, Notable Essays in Best American Essays 2016, 2019, and 2020, the QPB/Story Magazine Short Story Award and the 2018 Multi Genre Maverick Writer Award. She was named A Writer Who Makes a Difference by The Writer Magazine, and served as Inlandia Literary Laureate from 2012-2014, focusing on bringing writing workshops to underserved communities. She teaches at Antioch University and Sierra Nevada University.