Walking the Walls

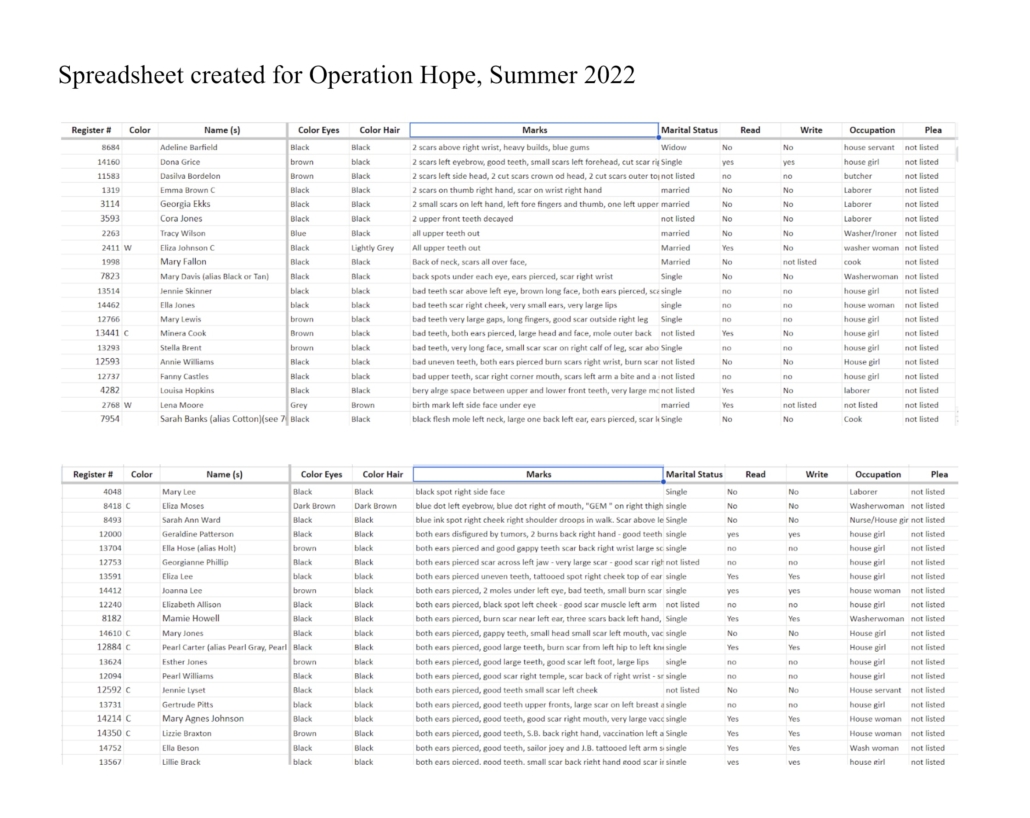

Every night I walk the Walls, a 12,382 cell spreadsheet of the names of women incarcerated at the first state Penitentiary in Baton Rouge between 1833 to 1913. The headers scroll past: Register # Color Name(s) Died Escaped Marks Crime Term Time of Conviction Please Name of Presiding Judge.

I am a fickle warden, careless. I move women around like chess pieces until their histories align in some order. It is an attempt to reconstruct the past, a way to collect ancestors, to remember what has been, to maintain order and stare a deadly system in the face. Perhaps it is a way to keep hope.

Hope is what Operation Restoration (OR) markets in. Based in New Orleans, OR provides resources to women impacted by the Louisiana Correctional system. They focus on providing education and vocational training. In 2021, a select group of women enrolled in a graduate level history class with the goal of creating a historiography of LCIW. Reluctantly, the prison officials agreed, but only from 1866 to 1900, just far enough in the past to be considered sterile.

The logistics of the project are mind-boggling. The incarcerated scholars are not allowed to leave the premises or spend excessive hours searching on the internet. Instead, they must rely on second-hand sources: scans of archived documents, reading guides and constructed spreadsheets. OR’s grants allot a mere $5,000 for a professor and a research assistant to undertake this enormous project.

For $20/hour for 10 hours a week for two months, I set about the Sisyphean task of creating a database that could be useful for the History Project. Examining penal codes, archeological digs, penal records, and photographs, I try to piece together the historical context out of which the Penitentiary system was created.

All summer, I worked within the behemoth of FamilySearch.org, laboriously extracting names from ledgers bound with human skin. I compare names between the Register of Convicts Received v. 8, no. 1-9073, 13 Feb 1866- 29 Dec 1889 to those in the Index of official register of inmates, v. 1, no. 1-9073, 3 Feb 1866-31 Dec 1889. Back and forth, I scroll between the 35-page registry for rural women and the 37 pages of New Orleans women until the names start to blur together. I still cannot grasp the magnitude of this project.

Their names follow me everywhere. Pauline Gross, New Orleans, 28, Black, Breaking and Entering A Store in Nighttime with Intent to Steal, 5 years. Stealing what? Why did Pauline decide to go in the nighttime? What was so valuable in a store to deem taking away 5 years of life? Reading further on, we learn that Pauline Gross was 5’ 2” native of Virginia with Black eyes and Black hair. She was married but could not read or write. She worked as a laborer. She had a cut on her breast, with a burn on her left nipple. I do not know how painful it must be to get burned so close to the center of one’s heart.

The youngest incarcerated woman is Vina Martin. Vina was sentenced to life in prison at 10 years of age for committing murder. I imagine the circumstances that would lead a 10-year-old to take a life. She was only 4’ 7”, roughly double the size of my son. What did Vina think on July 7th, 1877 as she sat in the courtroom, contemplating a lifetime in Angola? How can a ten year old understand what it means to spend a life in prison? Did the shackles leave a permanent imprint on her tiny little feet, did she still feel the yank around her waist?

The oldest woman incarcerated in Louisiana was 100 years old. Celeste Martin was convicted of the crime of slapping a white woman and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

The oldest woman incarcerated in Louisiana was 100 years old. Celeste Martin was convicted of the crime of slapping a white woman and sentenced to 10 years in prison. I wonder if after 100 years of servitude, Celeste just needed a moment of respite, a moment to assert herself, a momentary lapse of judgment? Due to the severity of her crime, Celeste could not even sit down in her cell. After three months, she was given a humane pardon.

***

In 1992, archeological firm Wurzburg and Hahn published Hard Labor: A Cultural Resources Survey of Old Louisiana State Penitentiary, Baton Rouge, Louisiana. In it, they detailed the results of a historical and archaeological dig conducted between August 1989 to March 1991.

Those sentenced to the Walls lived in glorified coffins. There were 240 cells in the Upper Cell house and 200 cells in the Lower cell house. Each cell was 7 by 3.5 feet, with no bed or cot and a solid iron door. An iron barred opening of less than 12 inches allowed for whatever stifled air could enter in the space. It is no wonder that the Daily Picayune in an 1844 article noted, “The average convict life is six years. It would, therefore, be more humane to punish with death all prisoners sentenced to a longer period than six years.”

It is difficult to ascertain where the women prisoners were kept as the Handbook is largely focused with the male prison population. In the beginning, the handbook makes some allusion to a gendered division of labor, noting that the women were “occupied in the washing and ironing for the convicts.” Later, in the midst of the Civil War, the book mentions that extensive damage to the female prison. The authors note that it cost Baton Rouge $2,224.75 to repair the female prison, including $1,475 to rebuild the garden and female prison fencing. In 1901, with only 5 incarcerated women, authorities transformed the old gin room into a Women’s Department. These are the only mentions of the women’s quarters.

***

As Brett Josef Derbes notes in “Secret Horrors: Enslaved Women and Children in Louisiana State Penitentiary, 1832 -1862” in The Journal of African American History, Louisiana was the only slave state that passed legislation that mandated the auction of children born to enslaved women inmates. Women who gave birth in prison were allowed to keep their children until the age of ten, after which most were sold to labor camps. The funds from these sales were used to fund Louisiana’s segregated public schools, meaning the betterment and education of white children.

Separating families is a beloved American tradition. I don’t know what it is like to raise a child knowing that they will be taken from you. I don’t know how to mother when you cannot even speak, how to provide comfort when every shred of humanity has been taken from you, how to soothe a child when you cannot even soothe yourself. I can try to grasp hope with its tiny feet and small cries. How could a mother and her children live in a room seven feet by three and a half feet, no bed or cot, an iron door?

Louisiana was the only slave state that passed legislation that mandated the auction of children born to enslaved women inmates. Women who gave birth in prison were allowed to keep their children until the age of ten, after which most were sold to labor camps.

One child, Priscilla, was bought by prominent slaveholder John Hill for $1,010. Mr. Hill would go on to donate $33,000 to Louisiana State University as the endowment for Hill Memorial Library. I walk by Hill Memorial Library every day on my way to Allen Hall where I sit in my cold office and contemplate Priscilla’s life. I wonder if she lived long enough to see Hill Library. Did she know that there were people years later who were looking for her against the grains of history? Priscilla, you are remembered. Priscilla, you are loved. Priscilla, you matter.

In “Twice Chained: Enslaved Women in the Louisiana State Penitentiary,” Maggie Tinley expands on Derbes’ words, adding that “In many ways, the experiences of these enslaved women are a historical anomaly. They formed a population that was exclusive to Louisiana and, more specifically, exclusive to Baton Rouge. The intense hardship these women faced and the uniqueness of their experience in Louisiana make them a critical part of the history of slavery in Baton Rouge.” Originally the number of incarcerated women was thought to be 35. What we found through Operation Restoration and the scholarship of Sarah Singh, a social justice and art curator at Xavier University, is that the true number of incarcerated women was actually much higher, since many women were held in the local jails before being sent to the State Penitentiary.

The flux and obfuscation of information feels intentional, to leave the public unaware of the true grasp of the horrors inflicted upon enslaved women in Louisiana. What happens to the stories not captured, to the details lost, to stories unwritten and unmapped? Who gets to determine the truth of the moment? What is the truth in this labyrinth? Somewhere I have lost the metaphor, the purpose of this essay. Somehow, I have to find the hope to keep pushing, to find some sort of meaning here.

Of the 1,310 artifacts collected from the site, there was a child’s shoe sole. From this one shoe sole, we can gather then that there were children residing in the Walls and that they were perhaps given the task of working in the shoe factory. In “Twice Chained,” Tinsley writes “Between 1835 and 1862, fifteen children resided in the Penitentiary with their mothers.” She goes on to list their names: Celeste, Frederick, Alfred, Joseph, Emilene, Henrietta, William, Clara Williams, Emily, Peter, Priscilla, Washington, Joe Wilson, Eli, and Joseph.

I like to imagine a moment of reprieve, of light. I like to imagine Peter and Clara and Emily walking in the garden. I like to imagine Celeste and Emilene and Henrietta touching the soles of their feet to dawn’s early dew. I want to think of Frederick, William, and Priscilla delighting in a cool breeze in the midst of Louisiana’s summer heat. Maybe Alfred, Joseph and Eli sang songs, maybe Joe held his mother’s hands. Maybe all the children ate dinner together, giggling, sharing bread. I know this is far from the truth. I write relief into their lives like a tempest. It’s the only relief I can offer.

***

We know so much and so little. Sometimes information conflicts and the women plot their escape between the lines of careful clerkship. Little indiscretions, little chances of life, little breathes of freedom.

Historian Saidiya Harman writes, “Waywardness is a practice of possibility at a time when all reads, except the ones created by smashing out, are foreclosed. It obeys no rules and abides no authorities. It is unrepentant. It traffics in occult visions of other worlds and dreams of a different kind of life. Waywardness is an ongoing exploration of what might be; it is an improvisation with the terms of social existence, when the terms have already been dictated, when there is little room to breathe, when you have been sentenced to a life of servitude, when the house of bondage looms in whatever direction you move. It is the untiring practice of trying to live when you were never meant to survive.”

We know so much and so little. Sometimes information conflicts and the women plot their escape between the lines of careful clerkship.

For weeks, I have been walking within the Walls, tracking the lives of wayward women of the past for wayward women of today. Typing the women’s names feels like invoking the past. Each square in my spreadsheet is filled with a story. I am not emotionally prepared for the scope of tragedy that can be contained in a spreadsheet.

I gather myself. I speak the names of the women and children forward. Vina Martin. Pauline Gross. Celeste Martin. Celeste, Frederick, Alfred, Joseph, Emilene, Henrietta, William, Clara Williams, Emily, Peter, Priscilla, Washington, Joe Wilson, Eli, and Joseph. Bring them to the light. Bear witness. Sometimes, I hope that is enough.

Nuha Fariha is a queer South Asian writer and author of God Mornings Tiger Nights (GameOver Books, 2023). Her writing has appeared in nat brut, MAGMA, and Road Runner Review and elsewhere. She is an Anaphora Arts Fellow, Charles M. Scrutchin Fellow, and Key West Writers Workshop Fellow. She holds an MFA in Poetry from Louisiana State University and lives in Baton Rouge with her family. Learn more at nuhawrites.com.