Trust Your Instincts and Follow Your Interests: A Conversation with Middle Grade Novelist Jack Cheng

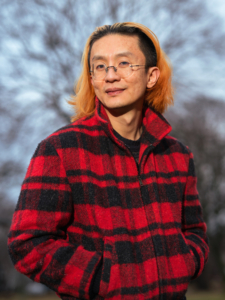

Jack Cheng is a Shanghai-born, Detroit-based author of inventive, character-driven stories for young readers. His Golden-Kite-winning middle grade novel, See You in the Cosmos, has been translated into over twenty languages. His newest title, The Many Masks of Andy Zhou, was named 2024 Best Book in Children’s Fiction by the Chinese American Librarians Association. He is a 2019 Kresge Artist Fellow and currently teaches Writing for Young People at Antioch University.

Cheng appears to be a born storyteller for young readers, yet he wrote his first book without a specific audience in mind, and only in revision did it become more specifically directed to “10-year-olds of all ages.” His second, more autobiographical book evoked vivid memories of his Chinese grandparents’ visit at the start of sixth grade and his turmoil and triumphs as he tried to find his place in a new school as a student and friend, and at home as a son and grandson.

Cheng didn’t always dream of being a writer. He built his own road with his desire for newness and love of learning that led him to advertising, tech, and writing in Brooklyn and back to Detroit, where he continues to write and renovate his home among many other projects. He and his partner have just begun the lifelong adventure of parenting with the birth of their son in July.

Lauren Howard: Thank you, Jack, for talking with me today. First, it has been a pleasure working with you as my mentor, and the only mentor working exclusively with middle grade and YA fiction writers. We’re very happy to have you here at Antioch this semester. I’d like to start by asking, what first drew you to write for middle schoolers?

Jack Cheng: I actually came to write for middle grades by accident. When I first started working on See You in the Cosmos, I just had this idea for a story about a boy and his dog trying to launch his iPod into space. I wasn’t necessarily thinking about the age of my audience; I was just trying to tell a good story. I knew of plenty of adult novels that had kid protagonists. It wasn’t until I sent a draft of the book to my literary agent that she said we need to be sending this to children’s and YA publishers. I said I didn’t really understand the difference but was willing to learn. Once See You in the Cosmos came out, I discovered this whole side to children’s publishing of school and library author visits that was very rewarding, getting to interact with the kids who are your readers or potential readers. I gained so much from that, I thought I’d love to keep writing for kids. Plus, if I think back, fifth and sixth grades were the years in my own life that were the most purely joyful.

I think I have a pretty good ear for dialogue. I have a daily journaling practice, writing the morning pages. When I was in New York, that involved writing down snippets of conversation that I heard randomly in the street. I also have the benefit of having readers who are hypersensitive to how kids speak.

LH: How do you develop just the right voice for your characters that will resonate with this age group?

JC: I think I have a pretty good ear for dialogue. I have a daily journaling practice, writing the morning pages. When I was in New York, that involved writing down snippets of conversation that I heard randomly in the street. I also have the benefit of having readers who are hypersensitive to how kids speak. My editor, especially in her line notes, will write: Is this the most kid-like way of saying this?

LH: When publishers suggested it would be a middle grade novel, did you have to go back and make a lot of revisions and hone in on your sensitivity to make sure you were thinking like a twelve-year-old?

JC: Some important but subtle changes included moving aspects of the story—those that skewed too adult or touched on emotions too intense for children—to the subtext so adult readers would still understand what was going on but the youngest reader of the book (probably an eight-year-old) could read it as a fun adventure story.

LH: I really enjoyed See You in the Cosmos and The Many Masks of Andy Zhou as an adult reader. Now that I’m focusing on middle grade books, I often wonder what makes a book a certain reading level, especially after teaching middle schoolers who arrive with vastly different reading and maturity levels.

JC: I feel like middle grade compared to YA is a little less genre-fied. The Many Masks of Andy Zhou, for instance, could have been a story about a kid joining his school’s dance production company, which does happen. But that’s not the only thing that happens. It’s one of the multitudes of Andy’s character. And I feel there’s a little more freedom to play with that.

LH: I know The Many Masks of Andy Zhou is autobiographical to a great extent.

JC: It was really difficult to write compared to See You in the Cosmos because it’s so personal and it meant revisiting a lot of childhood experiences of being bullied and microaggressed, not even knowing what to call it at the time. It’s very close to my heart and may be one of the most personal stories I’ll ever write.

It was really difficult to write compared to See You in the Cosmos because it’s so personal and it meant revisiting a lot of childhood experiences of being bullied and microaggressed, not even knowing what to call it at the time. It’s very close to my heart and may be one of the most personal stories I’ll ever write.

LH: Andy finds his true place at school as an artist designing the boar’s head mask for the dance performance of Lord of the Flies. Were you into art as a kid?

JC: Yes, definitely. I did a lot of drawing, especially charcoal pencil sketching. I felt like I was really good at making copies of things, drawing what was already there, but not dreaming up what to draw in my imagination. But I could look at what was in front of me, try to understand it, and have the drawing on the page reflect that. Other times I would just copy. I did a lot of Ninja Turtles.

LH: In the fifth and sixth grades, if kids are still into art, many start copying cartoon or anime characters and finding tutorials of how to do it step by step. It’s as if they’ve lost the freedom to create something on their own as they’re becoming more self-conscious, almost to a debilitating degree. Many middle school kids were drawing Sonic the Hedgehog when I was teaching.

JC: Even when you go to school for visual art, you start by copying the masters. Whereas with writing, typically you’re asked to be original and creative. There’s so much that can be learned, even if you simply type out a chapter of someone else’s story. It’s a way of understanding it that you can unlock in a different way.

LH: I really liked your recommendation and use of Sandra Scofield’s craft books, The Scene Book and The Last Draft.

JC: I’m glad to hear that. The Last Draft was very helpful for me in finishing The Many Masks of Andy Zhou. It’s a book that gave me language for what I was already doing and helped me reflect on those things. As a result, I was able to steer the story where I wanted it to go.

LH: You left Brooklyn after nearly a decade in advertising and tech to return to Detroit. What brought you back to your hometown—and can you tell us more about your connection to place?

JC: I grew up in Metro Detroit and went to undergrad at the University of Michigan. After that, I flew out to New York and lived there for about nine years. I had gone part-time at the company I had co-founded, a small tech design studio where I worked with a few friends. I was working from home so I could focus on my writing and realized that I didn’t have to be in New York during the winter so I ended up going to South America where it was summer.

I kept hearing and reading all of these stories about Detroit—that you could buy houses there for $500 for one thing. This was a different storyline from the frankly racist one I heard growing up in the suburbs: that Detroit is dangerous, and you don’t go there unless it’s for sporting events. I had a sense that neither of these was the reality. And I thought, why not come and spend time here and see what it’s actually like. I found a sublet in the city and had this stark realization the first night there that all of my close friends growing up had moved away. I did not know a single person in Detroit other than my roommate. The first thing I noticed was a real sense of community in Detroit. The neighborhoods and communities needed to be strong out of necessity because of the state of the city and the city government. That sublet became a full year lease and then I moved into a different apartment with the same roommate, and now it’s been about ten years.

LH: You must be happy there. Do you think you’ll stay?

JC: I’m very happy here and yes, I want to stay. We bought a house in 2017 that we did some renovations on and moved into right before the pandemic started in 2019. It’s been a work in progress. And I’ve never felt more connected to my community than I have here. Just walking up the street, we’ll see neighbors out on their porch so we’ll stop and talk.

LH: Considering neighborhood and architecture, could you elaborate on your interest in Christopher Alexander?

JC: A couple of years ago, I got a postgraduate architecture diploma in a program called Building Beauty, which is based on the architect Christopher Alexander’s work. He was known for putting out a series of books in the 70s, the most popular one being A Pattern Language, a collection of patterns that make for beautiful spaces. He was teaching at Berkeley and was very popular with a lot of hippies at the time who used his ideas to build their own houses.

I was a member of a book club that read technology related books, and Alexander’s work was selected because he was heavily influential in tech fields. The field of information architecture is drawn from his writings on design patterns in physical architecture. A lot of A Pattern Language seemed obvious or intuitive, but no one had written it down that way before.

A couple of years later, I found out about this program called Building Beauty, based in Sorrento, Italy at the time. It was meant for folks who already had undergraduate architecture or urban planning degrees. I remember taking a look at it and thinking, that’s great, but maybe in another life.

Then during COVID, I somehow ended up on that website again and saw that they had opened up the program to anyone with an undergraduate liberal arts degree. This was in part because there are so many Alexander fans who aren’t architects, and due to COVID, when everything was remote and online. I had a perfect gap between when I had finished The Many Masks of Andy Zhou and when it would be coming out to do the diploma program.

LH: Tell me about the app you created. Was that when you were in Brooklyn working in tech?

JC: No, the app Bebop is very recent. It was another spare time project earlier this year. I have this note taking system, where I save everything as plain text files in a folder. There’s an app on my computer I use to very quickly search through to find anything. But I needed the equivalent for my phone, and the app that I had been using was discontinued, and I couldn’t find anything else suitable. With all of the AI coding tools that had come out, I wondered how long it would take to use some of those to spin up an iPhone app to do what I needed it to do. I was able to get a prototype of that working pretty quickly, but it still took me a while to build it the right way and then be able to release it on the app store.

LH: With art, architecture, and tech, you have a lot of breadth in your interests and work itself. How do you fit everything in and still have time to teach and write?

After a while, you start to see some of the overlap and similarities between things. Any time you’re learning something new, you’re going through these same paces even though what you’re learning might be completely different. There are these rhythms you go through as you’re trying to level up. I’d say all of that is relevant to writing fiction.

JC: I just try to follow my interest and see where it takes me. Every career I’ve had started off as a hobby. When I was in high school, I would go on these Photoshop contest websites. I’d rush home from school and try to put together funny entries. I learned Photoshop and graphic design that way, and that’s how I got my first job in advertising. When I worked in advertising, I learned to code and build my own website. My next career was in tech. I started keeping a journal and that led to writing a novel. I’ve always trusted my instincts and followed my interests. It has never steered me wrong.

LH: You’re really carving out your own destiny. Most people don’t allow themselves or have the flexibility to use so many parts of their brain.

JC: After a while, you start to see some of the overlap and similarities between things. Any time you’re learning something new, you’re going through these same paces even though what you’re learning might be completely different. There are these rhythms you go through as you’re trying to level up. I’d say all of that is relevant to writing fiction.

LH: Have you taught in an MFA program before? What do you most hope to impart to your mentees, and what have you learned so far about yourself through mentoring?

JC: Antioch is the first time that I’ve formally taught in an undergraduate or graduate program. I’ve run workshops in the past, but to do an entire semester is new for me. Coming in, I was feeling a bit of imposter syndrome about being an instructor because I haven’t gone through an MFA program. I had to keep reminding myself that I have my own experiences and those enable me to bring a unique perspective and my own approach toward writing.

LH: That appealed to me. I value the enthusiasm, freshness, and openness you bring to the program. As students, we gain surprising and useful knowledge from our mentors’ writing and lived experience. I almost forgot about your podcast BookSmitten.

JC: I co-host with a few other children’s and young adult novelists. We all happen to be based in Michigan but have audiences that go far beyond that. Our first season was just sitting around talking about children’s literature. In our second season, we decided to independently create a picture book, so we interviewed picture book authors, illustrators, and editors along the way.

LH: Did you get a picture book out of that second season?

JC: I ended up co-writing mine with my partner Julia. We sent a draft of it to the editor of my middle grade novels. She gave us some feedback from her colleagues, and based on that, we had started on a rewrite of that picture book. Then life got in the way of turning it in.

LH: Yes, that brings me to the final question. How do you think becoming a parent will affect your writing in terms of both practice and content?

JC: Well, he’s only five and a half weeks right now, at peak gassiness and having his nightly witching hours. The manuscript I’m working on revolves around a family, a single father with three kids. It’s really making me think more about what the father might be going through and bringing up a lot of empathy. I’m just starting to get a better understanding and appreciation of my own parents’ experience with me and my brother. I think there are a ton of things that are yet to be foreseen.

LH: Is this current project a middle grade novel?

JC: I’m not sure if it’s middle grade or young adult. I had a conversation with my editor, and she said not to even think about that right now and to remember what it was like when I was writing See You in the Cosmos. And I think that’s really great advice.

LH: As far as writing time goes, I remember my sleep patterns got so disrupted that I would feel wide awake after two hours of sleep and could never go back to sleep after I was up in the middle of the night. So that’s when I started nocturnal writing, and I never really shook it.

JC: The middle of the morning is my sweet spot for writing and my partner and I are trading shifts and settling into a routine. It’s been hard this first month or so to even read anything without going to sleep. I’ve never been one to fall asleep spontaneously on the couch, but this is a new kind of exhaustion. Every day I have two or three hours of time to myself, and I might get an hour to work on my manuscript.

LH: On that note, I must let you get back to your family and your writing. Thank you for your generosity as a teacher and a writer, and for being so thoughtful and adept at speaking about your work.

Lauren Howard lives in the Bay Area with her husband and has two grown children. She worked at SFMOMA for twenty five years in marketing and education and later taught English in underserved areas of Marin County. She is currently an MFA candidate in Fiction: Writing for Young People and CNF. Her poems have appeared in Written Here, The Community of Writers Poetry Review, and the The Marin Poetry Center Anthology.