A Case for Emotional Truth

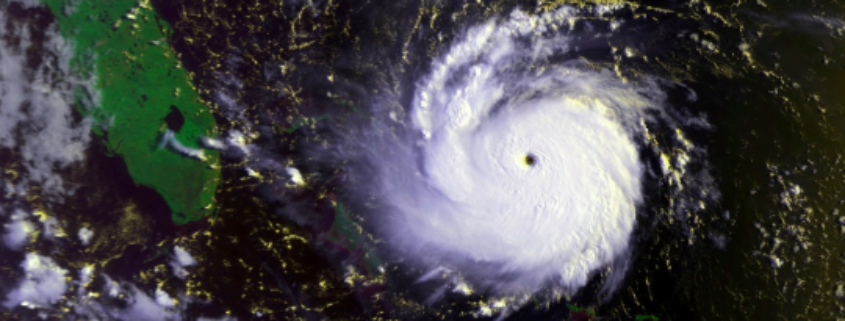

This much I know to be true: Hurricane Andrew made landfall near Homestead, FL, in the early morning of August 24, 1992. Winds reached 165 miles per hour at their height, aside from the resulting tornados, and the rainfall averaged eight inches in Miami-Dade County. Twenty-six people died nationwide as a direct result of the storm, with another forty dying from indirect causes, although my father heard rumors that many more body bags were packed into a stadium, and undocumented migrant workers weren’t counted in the death toll. My mother, sister, and I flew to Virginia the day before the storm. Mom had planned the vacation months before. Dad stayed in South Florida. Our roof lost three-quarters of its shingles and tar paper, which made the house vulnerable to rain. Water ran into the attic and seeped down through ceiling fans and lighting fixtures. Our carpets, clothing, furniture, and toys were destroyed if not immediately by the water, then by the mold that developed afterward. Our shed and everything inside it blew away.

This much I also know to be true: in August of 1992, I was three years old. My mother collected my toys onto the back patio, where I was tasked with discarding anything damaged. Mom documented everything we tossed for our insurance claim. I lifted the toys one by one to my nose, sniffed, and then, with great authority, said, “Claim it!” Mom assured me everything was replaceable. Twenty-two years would pass before I began to attribute the destruction of my home and belongings to why I form little attachment to place and material possessions.

By definition, truth implies something is in accordance with fact or reality. Which calls on writers in the sticky genre of creative nonfiction to define reality, a word literally defined in the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “the world or the state of things as they actually exist, as opposed to an idealistic or notional idea of them.” Does perception not shape our individual realities? Or does reality belong solely to that which is proven factual and apparent to all? Who’s to argue it wasn’t the storm that made me less attached, less sentimental toward belongings, when I know that to be true?

The day after Hurricane Andrew, when my father drove from Broward to our home in Cutler Ridge (now Cutler Bay), people were cutting down trees so cars could navigate the streets. It’s true that during the drive Dad saw houses leveled or roofs blown away; inside those homes one could look up and see only sky. It’s true the National Guard patrolled the streets with guns to ward off looters, there was no electricity for almost a month, and the neighborhood organized a schedule so that every day the responsibility of preparing dinner for the whole neighborhood fell on only one household because food was hard to come by.

What’s not true, at least not in the way truth is defined—concrete, absolute—is that when my father arrived to see our home still standing, albeit undeniably damaged, the sight was a relief: it was fixable, he told me. Because had another person, in the same circumstance but who brought to the experience their own knowledge and expectations, seen their house in this state, they may have felt something entirely different.

When my mother returned to Miami with my sister and me three weeks after the storm—we had stayed in Virginia, as Amy was only ten months old and crawling—Mom told me she felt disturbed by the insurance policy numbers spray painted on houses. She felt obliged to be tough and proactive. At my young age she was unsure what I would remember, or what could hurt me. It was only after dinner at the neighbor’s house, after my sister and I were sponge-bathed and kissed goodnight on the mattresses on the floor, after the lights turned off, that my mother smelled the mildew in the walls and started sobbing.

I called my mom to ask her about the hurricane for the purpose of this essay. She said then, “Something really bad happened, and you found out real quick what you were made of.”

* * *

When writing creative nonfiction, we aren’t reporting news; we’re reporting life the way the author feels and internalizes it—if nothing else, CNF is entirely representative of an individual’s emotional truth. An individual’s perspective. Don’t humans navigate the world emotionally? Who’s to say which reality holds more weight: that 126,765 homes were destroyed or damaged in Hurricane Andrew, or that Mom felt devastated because while she could not decipher what the piles of debris in her home consisted of, she knew at one point whatever it was had been important to her?

There are two schools of thought dividing the debate. Joan Didion champions emotional truth, while Tracy Kidder argues for reporting facts and facts alone. In Didion’s essay, “On Keeping a Notebook,” she proposes that journaling is not for keeping a factual record, but rather to remember how it felt to be her. She writes, “The cracked crab that I recall having for lunch the day my father came home from Detroit in 1945 must certainly be embroidery, worked into the day’s pattern to lend verisimilitude; I was ten years old and would not now remember the cracked crab.” But no matter how fictitious the cracked crab, that detail allowed Didion to later envision the afternoon with her family, “a home move, the father bearing gifts, the child weeping.” The emotional truth far exceeds the minute, often overlooked details, like what one ate for lunch.

Minds are not recording devices for memories. Sensory memory—that which allows one to retain environmental information, including (but far from limited to) the light of the room, the texture of the seat on which you sit, the noise of the traffic outside, the vase in your periphery—decays in seconds, unless retained in one’s short-term memory through what’s called the “process of attention.” Short-term memory cannot hold complete concepts and acts more accurately as a notepad, usually jotting up to seven memories that can be recalled within 20-30 seconds. Memories are only then transferred into long-term memory by associating that memory with something else or bestowing it with meaning.

Which is to say, memory, flawed and unreliable as it is, ultimately pulls through—as best it can—when emotion’s applied. Dad remembers throwing chlorine on the mold; Mom remembers the mold making her cry.

* * *

In my first memory, I sit on the front porch of my grandparent’s house in Virginia. Dad phone calls for Mom.

Later I’d learn this happened three days after the hurricane; it’d been all radio silence and news reports before then. When my mother went to the local store and saw friends who knew of our family’s move to Miami, she couldn’t answer their questions: Where’s Tom? Is Tom safe? My father’s mother would call, panicked: have we heard yet? Where is he? The news plays in the background, talks of looters, images of destroyed homes.

I remember my grandfather on the white rocking chair, my newborn sister on the ground by our feet, my mom standing in the doorframe. Dad is okay. He is fixing the house.

Was my newborn sister really crawling by our feet? Was she instead cradled in my mother’s arms, or bouncing on my grandfather’s knee? Did I simply place us on the porch because on that porch sits my Pap Pap’s favorite chair, but in reality we sat around the dinner table or in the basement with deer heads mounted on the walls? I remember the scene vividly, as if twenty-three years later I can still feel the weather coming through the screen enclosure. Was there a screen enclosure? Perhaps in the years since I’ve filled in the gaps, applying knowledge and perspective acquired much later, to make that day feel real.

What mattered that sunny afternoon on the porch—or in the dim light of the basement, that evening during dinner—was Dad survived the storm. The relief and joy were palpable to all of us; the location hardly mattered.

Lyndsay Hall lives in Los Angeles where she teaches writing to children and teens. She is pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University and she serves as an editor for Lunch Ticket, Zoetic Press, and Prague Revue. Her essays have appeared in xoJane, Rhizomatic Ideas, and elsewhere.