A Queer Declaration

Over the weekend, I watched Gaycation for the first time. This investigative series follows Ellen Page and her best friend Ian as they examine LGBTQ+ culture and laws in different places around the world—something that interests me as a queer woman in the United States. While watching and hearing the varied views on the implications of being gay, realizations started churning within me of my own struggles with self-acceptance, inwardly and outwardly, past and present.

Then my phone rang—my girlfriend in Kansas. What are you doing? she asked, always eager to know what I’m up to 1,568 miles away. I told her what I was watching and asked if she ever saw it. Um, no, I think that show is similar to Gay Pride parades for me. Me, head-scratching, as confused as I was about my crush on Avril Lavigne when I was thirteen-years-old: Oh, okay.

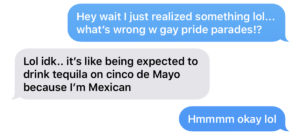

I let it go, but after we hung up, I kept thinking of her tone when she compared it to Gay Pride, so I sent a text.

Me: Wait… What’s wrong with Gay Pride parades?

Her: Lol idk… it’s like being expected to drink tequila on Cinco de Mayo because I’m Mexican.

Again, I let it go, but I kept thinking of the Stonewall riots, the 1969 uprising that essentially turned the wheels on LGBTQ+ rights in the U.S., and of all the injustices committed throughout the years against members of the LGBTQ+ community. I thought about how my gay brother hates going to “straight bars,” because you never know what discrimination you’ll face outside of safe spaces, and I thought of all the enraging reasons safe spaces exist in the first place. I thought about growing up in the stifling state of Kansas and how I’d never been to a Gay Pride parade until I was twenty-eight years old and living in California. I wondered if she thought about any of this or if, to her, Gay Pride celebrations were just an excuse to party.

At that moment, I decided, and declared on Facebook:

“I WANT TO WRITE THE MOST ELOQUENT, ACCESSIBLE QUEER SHIT I CAN WRITE TO HELP OTHER QUEER PEOPLE KNOW IT’S OKAY TO BE QUEER.

And, yes, that needed to be in all caps.”

It needed to be in all caps because I was trying to convince myself it was okay just as much as I wanted others to know it was okay.

* * *

Growing up in a small town in Kansas, raised by a Mexican father and a German mother, identity was a tricky thing to navigate even without the “queer.”

When I was twelve, my brother asked me to his room, telling me he’d like to talk to me, to tell me something important. I was hesitant—I loved my brother, but we weren’t exactly best friends at that age, so I wasn’t sure what he’d want to tell me.

I stood at the side of his bed, near the door, as he sat at his desk, then turned to me and said, “I’m gay.” Without needing to process, I just said over and over, while smiling, “I knew it, I knew it!” He laughed and asked, in disbelief, how I could possibly have known, causing me to think about all the times he pretended to be Britney Spears, flipping his fake long hair as often as he mirrored her choreography. In hindsight, this wasn’t actually a good indicator of his sexuality, but it happened to be the connection my young mind made. We talked about his experiences up to that point and everything seemed fine. I mean, I knew he was going to deal with hardship with our family and school and the world in general, but everything between us was fine.

I didn’t understand at that point how it could or would affect me, but it became a huge hindrance for my own acceptance of self.

* * *

You can’t be gay—your brother’s gay. One gay per family. What I’d tell myself.

You just haven’t slept with the right man yet. What others told me.

I spent the next sixteen years conflicted about my sexuality. I had a couple girlfriends in high school—mostly only “out” because that’s what they wanted, though it made me uncomfortable to walk the halls holding their hand with all those eyes staring.

My first adolescent long-term relationship ended when I was fifteen. After a year and a half, she cheated on me with a guy from work, and then left me for a boy from school. When she was breaking up with me, she asked in an accusatory tone, “How do you know you’re really gay if you haven’t even slept with a guy?”

The overthinker that I am, I thought about this for weeks. And then I found an opportunity with a male classmate, a guy I thought was cute but who I was otherwise disinterested in. He picked me up in his truck one evening and we drove to a park near my house where he turned off the engine and leaned over to kiss me. As he climbed over the middle console, unbuttoning his jeans and then mine, and then positioning himself on top of me, I panicked briefly, wondering what I was getting myself into. I tried not to let my apprehension show as he brought his body down to meet mine, and then I instantly got lost in thoughts of a girl I admired, picturing her sitting on the steps in front of the school where I always saw her reading by herself. I thought about her and then it was over—I’d successfully had sex with a male. And then I thought, Okay, well, now I know.

But I didn’t know, because then the more predatory conversations came, the ones that went: He probably just wasn’t any good. You need to sleep with me to find out.

Again, the overthinker that I am, I thought about that for years. Thus began a pattern of getting blackout drunk and giving myself to men—a pattern that lasted eleven years, starting when I was seventeen, fresh out of high school with no plan for the future. I didn’t question whether I was interested in women; I knew that I was, but I questioned whether I could actually not be into men, because society made it really fucking hard to believe that was possible. I wanted so badly to be interested in men—to fall in love with a man, to marry a man, to have children with a man, to give my parents and society what they wanted because everything would be so much easier that way.

But that never happened.

* * *

Society, along with many personal demons, had really warped my sense of self.

At twenty-eight, I’d find myself on Tinder, changing the settings from “Women Only” to “Men and Women,” but taking notice that any interest I’d have in men at that point had more to do with self-deprecation. I’d get into these moods of wanting to be used, of wanting to be treated as lowly as I felt about myself, and so I’d swipe right on an influx of men, and I’d read the mostly disgusting messages objectifying me, and I’d respond to a handful and tell them I was only interested in hooking up—but I could never bring myself to follow through.

* * *

And so, on episode one of Gaycation (“Japan”), when Ellen Page said how important it was for her to no longer be in hiding and how the level of toxicity of it was just so extreme and wanting to be in love and to love someone openly was far more important to her than being in movies or having someone dislike her for her sexuality, it resonated with me. I was tired of going to family reunions and having to play the game of being heterosexual with my dad’s straight-laced Christian family. I was tired of introducing girlfriends as just friends. But mostly, I was tired of hating myself for not being what made others comfortable, as if their comfort was more important than my self-worth.

I thought of the gay culture I’d experienced since moving to southern California and I thought of how my most recent love interests would ask me how I felt about public displays of affection. I thought of how I’d tell them I’m only sometimes okay with it, and then how sad it made me when they’d later ask, “Am I allowed to hold your hand here?” How they’d follow with, “Are you sure?” when I’d say, “Yes,” because they loved me enough to not want to make me uncomfortable, when all I really wanted was to love them and to be loved by them, regardless of the world around us.

I thought of the gay culture I’d experienced since moving to southern California and I thought of how my most recent love interests would ask me how I felt about public displays of affection. I thought of how I’d tell them I’m only sometimes okay with it, and then how sad it made me when they’d later ask, “Am I allowed to hold your hand here?” How they’d follow with, “Are you sure?” when I’d say, “Yes,” because they loved me enough to not want to make me uncomfortable, when all I really wanted was to love them and to be loved by them, regardless of the world around us.

So when I declared “loudly” on Facebook that I want to write the most eloquent, accessible queer shit I can to help others know it’s okay to be queer, I was making a declaration to myself. I was declaring to write shamelessly about my truth and the truth of so many others, of being a woman who loves women and of learning to love myself by accepting that and sharing it with the world. I was promising myself to stop letting society dictate who I am, and who I have sex with, and who I love, and when and where I hold hands with or kiss or even hug the person I love.

Because if I write about it, if my goal is to help other queer individuals shed the shame, I most certainly have to come out of hiding and be about it.

Alisha Escobedo is a marketing coordinator and an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. She also works as proof edit assistant manager for Lunch Ticket. Her work can be found in Desolate Country: We the Poets, United, Against Trump and Prompts!: A Spontaneous Anthology. Originally from Kansas, she currently resides in Long Beach, CA.

Alisha Escobedo is a marketing coordinator and an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. She also works as proof edit assistant manager for Lunch Ticket. Her work can be found in Desolate Country: We the Poets, United, Against Trump and Prompts!: A Spontaneous Anthology. Originally from Kansas, she currently resides in Long Beach, CA.