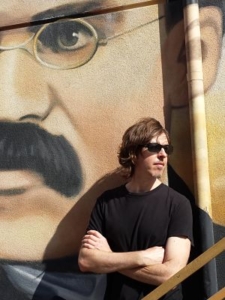

Alistair McCartney, Author

Photo Credit: Tim Miller

Alistair McCartney is more apt to graciously smile and walk by, than stay and chat. Amiable and courteous, he’s an unassuming type who stays out of the spotlight. Author of The Disintegrations:

The Disintegrations cobbles together nightmares, legends, haunts, and tender recall into a larger story that allows for deep reflection and interpretation.

Born and raised in Perth, Western Australia, Alistair McCartney resides in Venice, California. He is on staff at Antioch University Los Angeles teaching fiction for the MFA in creative writing program, and oversees AULA’s undergraduate creative writing concentration. Included in the list of institutions where he has presented are CUNY Grad Center, PEN Center USA, AWP, Teacher’s and Writer’s Collaborative New York, and UW Madison. Usually dressed in a slim tee and slacks, his longish hair waving over one eye, Alistair brings cups of tea and total focus to his workshops.

I had the opportunity to work with Alistair during a creative writing residency at Antioch University’s MFA program. When my packet arrived stamped with his name, I wanted to bellow a loud huzzah, but whispered, yes, to my napping hubs, I’m workshopping with Alistair McCartney. At the workshop, I felt awed by Alistair’s humor and unshakable calm; the way he doesn’t trip on words. His latest novel, The Disintegrations was nearly finished, he told our group. He raked through his hair and described the task. Nine years of work, building, disassembling, paging through text, and here I was witness to the last phase of its completion. It only takes nine months to birth a baby. Holding the new novel and reading it through winter break, I could hear Alistair’s gentle Australian-accented prosody narrating in my head.

The Disintegrations cobbles together nightmares, legends, haunts, and tender recall into a larger story that allows for deep reflection and interpretation. Also named “Alistair,” the novel’s narrator is unapologetic, sometimes seedy, and never predictable. McCartney presents briefly penned inquiries, snooping for small answers to the big question: What does the exploration of death reveal about life?

I interviewed Alistair McCartney by email in February, 2018.

Andrea Auten: Your recently published novel, The Disintegrations, packs thick and richly worded text exploring death’s parlous hold on its narrator, and though the piece is small, it contains profound discoveries. In intimate partnership, I walked through death’s shadowy valley in what felt like an epic thousand-page novel and never felt cheated or unquenched. What methods helped manage the size and scope of death and in paring down the text, how did large cuts affect your writing and serve this story?

Alistair McCartney: That makes me so happy to hear that your reading experience was one of intimacy, and that the book felt epic in scope, within the limits of its 213 pages. If I learnt anything from the process of writing this novel, it was how to compress, how to be ruthless in cutting. Earlier drafts were three times as long.

What guided me through this process was an ethos that I address directly in the book, that in trying to write about death, the temptation is to go on and on, to write a novel of Moby Dick proportions, but instead I followed an instinct that the writer should be more modest in his aims.

In The Disintegrations I use the analogy of wanting to write a book like a grand cathedral of Gothic dimensions, but instead aiming to create a structure that has the strictly controlled dimensions of a grave, a book whose space is contained, but full of hidden things.

I think, or I hope that this method served the voice, brought forth a terse quality in the narrator, and served the story in terms of avoiding grandiosity or portentousness. It also helped speed things up in terms of pacing; some readers have told me they read the book in one sitting, which also makes me happy.

AA: I enjoy your form of archival writing; this collective sourcing. When all is available can it become a flood and how do you navigate and know what to keep?

AM: I love that you pick up on the archival nature of The Disintegrations. Just as with The End of the World Book, I played the role of an encyclopedist; in this new book I’m essentially an archivist, responsible for maintaining the archives of the dead, though one who is not averse to tampering with the documents, falsifying them. And it gets me wondering if all writing is archival by nature, to some degree.

The specter of Catholicism was unavoidable in this book especially given the setting at a Catholic cemetery, given the narrator’s (and my own) Catholic upbringing.

Your notion of the flood is definitely apt, it’s exactly what I was confronted with as I researched and wrote successive drafts: a deluge of documents, records, facts, information. As for how to deal with it, I think you have to drown for a while in all of it, but after the deluge, you begin to intuitively keep and take only what draws you with a kind of magnetic pull, what sparks your imagination.

AA: I have a vivid childhood memory of losing myself in the worn-out album cover of Elton John’s Captain Fantastic, an older brother’s hand-me-down classic, while listening to songs like “Someone Save My Life Tonight” and staring at the Bosch-inspired cover art. Bosch’s real painting, “The Garden of Earthly Delights” both frightens and fascinates, with Adam and Eve, all of the people on earth, and the darkening end times depiction. As you wrote The End of the World Book and The Disintegrations, how might Catholic iconography have attached to your themes?

AM: Your childhood memory sounds very similar to my own—I was obsessed with music and visual images, including Bosch’s art, especially that right panel of The Garden, his depiction of Hell. Your choice of words as to the effect of his images, both frightening and fascinating, is spot-on. Weirdly enough in an earlier draft of The Disintegrations I wrote about Bosch; I ended up cutting it, but will go back to it in another book that is part of the cycle I’m working on.

The specter of Catholicism was unavoidable in this book especially given the setting at a Catholic cemetery, given the narrator’s (and my own) Catholic upbringing. I think I should leave it up to readers and reviewers as to how it specifically impacts the book’s set of icons, but I will say that the theme of resurrection versus disintegration is obviously central to The Disintegrations. The narrator draws on religious motifs throughout, not just of the Catholic variety, but always through a non-systematic lens. As I wrote I was thinking a lot about writers and artists who draw on religious imagery in a reverent yet deeply idiosyncratic way, like Flannery O’Connor, Dostoevsky, and my fellow Australian Nick Cave.

AA: Your work, nonlinear, archival, the spaces in between, evokes visual art movements—beyond surrealism, somewhere less Dadaistic—where interpretation and interaction meet. What are your visual art interests and how do they help you paint words?

AM: Yeah, I’m definitely a writer who’s profoundly influenced by other art forms—music, dance, film, and as you mention, visual art. In a very general sense, I’m drawn to the immediate power of the image, the sensual materiality of visual art; my writing is very image based—images are more important than plot or narrative.

There were several artists whose work really informed The Disintegrations, images I kept on my desk as I wrote: Alice Neel’s portraits guided the fictional eulogies, El Greco’s painting of The View of Toledo served as sort of talisman for the setting, Marlene Dumas’ stark portraits in her Measuring your Own Grave exhibit were invaluable, as were the disintegrated photographs of Costica Ascinte (one of his photos ended up on the cover), and Banks Violette’s abstract Black Metal inspired installations. All these works shared a beauty and intensity that helped me figure out how to write around death, through death.

Because all my writing begins with fragments, I’m deeply drawn to the visual art method of collage, it teaches me so much —I’m fixated on that now as I work on my next book. Also, installation artists like Danh Vo, who works with the accumulation of disparate objects into a non-linear narrative. And I have a future book planned for my cycle that will, God willing, address my passion for visual art directly.

AA: How does performance art and its world weave into your writing and inspire you?

AM: Well, I do have a background in performance art and live art. I spent a good chunk of the 90’s in London and in LA experimenting in that zone, doing both text based work and movement focused, body centered work without text. And I used to teach a class on the history of performance art, Vibrant Bodies, to the undergrads at Antioch, focusing on extreme performance, like Chris Burden, Ron Athey, Kira O’Reilly, Franko B, Marina Abramovich, William Pope, L. Regina Galindo, and others.

When I was a practitioner, I was kind of trying to avoid being a writer, though I had to go back to it, it’s just who I am and what I do. But that trace of performance lingers in my writing; a review of The End of the World Book said that the voice and prose was like that of a performance artist, or an avant-garde stand up comic. For that book I did some directly performative readings, using a slideshow, and playing with volumes of the actual World Book during the reading.

And I think The Disintegrations is also very oral in nature, it’s a book to be read aloud, which is how I write, reading every sentence over and over again aloud until it sounds right. Essentially I approach writing in a very performative manner; for me that “I” who narrates my books, who bears my name, is a persona, a performative gesture. It’s interesting you bring up performance because I suspect I may be exploring it more actively in the third book, both in terms of the writing on the page but off the page as well.

AA: What sparked your love for French auto-fiction and how did great minds such as Bataille, Rimbaud, Genet, Guibert, and Blanchot influence your work?

When I teach fiction, truth is not a word I reach for, but I use other words or concepts that perhaps are variants of the term. For instance, when I’m reading my student’s novels and short stories, I’m drawn to identifying the singularity of a writer, and encouraging them to pursue that uniqueness.

AM: Well, all those writers you mention are ones I love and have informed me at different stages of my life. Genet, Bataille, and Rimbaud are writers I discovered as a teenager; Guibert in my mid-twenties, Blanchot more recently. And to that list I’d add Duras, who I first read as an undergrad. Specifically in terms of those writers whose work falls under the category of auto-fiction—Duras, Guibert, Blanchot—I’d say it was an immediate resonance with the work, their “choice” to write explicitly from life, but refuse the category of fiction, and in Blanchot’s case, to question the very grounds of representation. I’m making this attraction sound very cerebral, but it was much more instinctive. All of my work begins in the autobiographical, but I just don’t feel comfortable telling it in the realm of creative non-fiction. Blanchot’s Death Sentence was a novella that had a major influence on The Disintegrations in helping me find the right voice and register to tell my fictional eulogies.

As for the other writers you mention who don’t fall so neatly into auto-fiction, with Bataille, his exploration of the erotics of transgression and the interface between sex and death is definitely there in The Disintegrations. In many ways I think of the shorter sections of my book that read like prose poems as direct descendants of Rimbaud’s The Illuminations, like negative mirror images of those poems. Even the title of Rimbaud’s book influenced my title. I’m not sure Genet’s influence is directly in the current book, but interestingly enough he’s someone I’ve been thinking about lately, and who is definitely influencing the world of the new book I’m working on.

AA: All this clanging about fake news, truth v. fact, grappling with the nature of truth is not a new social construct. Ancient Greco-Roman rights and illusions of free speech, Foucault’s “games of truth” thinking, the splashy recrimination hurled at not so nonfiction writing; truth has pliancy. As a teaching artist how do you assist writers to search for their own relationship to truth?

AM: That’s a really interesting question, because the word truth is one that’s not really in my vocabulary, at least as it applies to art. I think I’m still very much a child of post-modernity; Nietzsche’s assertion that “truth is a mobile army of metaphors” is one I’ve been very aware of lately. I’m fine with Plato labeling us as liars—he can keep his Truth.

So when I teach fiction, truth is not a word I reach for, but I use other words or concepts that perhaps are variants of the term. For instance, when I’m reading my student’s novels and short stories, I’m drawn to identifying the singularity of a writer, and encouraging them to pursue that uniqueness. I’m really excited by my students doing work that’s provocative, that’s pushing at a limit, that’s fearless. All of this is my way of encouraging the writer to follow their aesthetic vision, which is perhaps, a sort of truth, or more essential than truth. Encouraging the writer to counter that “clanging” in the social sphere you mention, with the—to take Nietzsche’s words—“sensuous vigor” of their language.

Perhaps the closest I get to applying the concept of truth to fiction is when a student is doing work with a basis in history, and their work is intent on revealing historic truth, especially through defamiliarization. That’s where I have to separate my own aesthetic or philosophical discomfort with using the term, particularly when I write, my sense that language is not a medium that has access to truth, from the importance of my student’s vision and from the strategic importance, in our age, the necessity of asserting the value of historical truth to counter the dissembling forces of fascism here and globally.

AA: What role do writers have in influencing culture and do you see that increasing or decreasing?

Helen Cixous says that children read with extreme violence, in that they erase the rest of the world when they read. I think if we can write books that intuitively tap into that obsessive focus, that childish curiosity, that textual hunger, that free zone where no limits were placed on the imagination, where narratives were unpredictable and we were more than happy to go along for the ride, maybe then we’ll keep our readers eager to turn the page, longing to finish their daily obligations and get back to the book.

AM: Wow, “culture” is such a big concept, I’m not sure what it means anymore. I think we did see in the 20th century the splintering of the notions of high culture versus low culture, the de-centering of the writer as influencing cultural trends in a grand way. Sure, some big names have a platform in their books and op-eds and speeches where they are able to reach an audience large enough to have some broader influence, but I think most of us, if we have any influence, it’s in the literary communities we find ourselves in, whether those reside in an institution or outside an institution. It’s also in that intimate relationship between individual writers and individual readers, those readers we touch and who reach out, so we can communicate with them. That sphere of influence is very significant.

AA: Our two rows of The World Book Encyclopedia shelved behind the family couch frequently called me to lie on my belly and consume information. While I read your novels The End of the World Book, drinking its humor and interiority, and The Disintegrations, marveling at the depth and uniqueness of its characters, I considered how you crafted the works to make me crave and hungrily keep reading. What makes readers want to continue reading?

AM: I love hearing how other readers shared the same passion as mine for The World Book when they were kids. The other day I was telling someone how in the last few years, and even more recently, in the last year since The Disintegrations came out, I’ve learned to read like a kid again, with the same intensity and joy. Helen Cixous says that children read with extreme violence, in that they erase the rest of the world when they read. I think if we can write books that intuitively tap into that obsessive focus, that childish curiosity, that textual hunger, that free zone where no limits were placed on the imagination, where narratives were unpredictable and we were more than happy to go along for the ride, maybe then we’ll keep our readers eager to turn the page, longing to finish their daily obligations and get back to the book.

AA: How might writers adhere to current publishing standards, while tooling the piece they’re compelled to write, honoring their own voice and truth?

AM: Well, we all want to get published, which means having to meet “a publishing standard” established by a house, an editor or agent, a system. But I think it’s really important as writers we write the books we’re meant to write, in all their singularity, ignoring all publishing conventions. So I guess it’s a question of simultaneously pushing the limits of standardization, writing what we need to write while finding those editors, publishers, especially the small independent houses, and locating those journals that welcome singularity and idiosyncrasy.

AA: Flashbacks seem to be on a downturn yet The Disintegrations utilizes recall, reverie, and rumination to successfully invoke a storyteller’s voice. How do you keep your narratives active and where do you think the industry trend is headed?

AM: Yeah, reverie is an important aspect of The Disintegrations and The End of the World Book. I’ve been plugging away at Proust again—I’m only up to book three, The Guermantes Way—and I realized how much his fetishization of recall has influenced me, albeit gathering memories in a far more fragmentary method than his. I’d say the active element of my narratives comes by way of image and motif, the accumulation of memories and images, the reverb of motifs that the reader recognizes and hopefully takes pleasure in.

As a teacher of MFA fiction writers, I am aware that the use of flashback in conventional narratives can drag the narrative down, but, as with the previous question, I do think writers should be wary of any fixed rules and write against such a convention. I’m afraid I don’t pay much attention to “industries” or “trends” so I can’t tell you where any of that is going, but my hope would be that we keep letting in more of those voices that don’t meet market expectations, those voices that don’t fit any trends.

Andrea Auten is the Amuse-Bouche editor for Lunch Ticket’s thirteenth issue. A masters candidate in creative writing at Antioch University Los Angeles and an arts teacher and performer from Dayton, OH, she lives and writes in Los Angeles. Her work can be found in The Antioch Voice. She is currently finishing her second novel.

Andrea Auten is the Amuse-Bouche editor for Lunch Ticket’s thirteenth issue. A masters candidate in creative writing at Antioch University Los Angeles and an arts teacher and performer from Dayton, OH, she lives and writes in Los Angeles. Her work can be found in The Antioch Voice. She is currently finishing her second novel.