It’s Always Harder than it Looks

Mt. Rubidoux. Photo credit: G.D. Palmer

Recently, my son Quentin called to report that he’d summited Mt. Rubidoux and would be home soon for dinner. I chuckled. Mt. Rubidoux is, more accurately, a hill that rises 500 feet above the Santa Ana River in Western Riverside. Under most circumstances, “summit” would be excessive, though that was not the case the first time that Quentin climbed its steep west side.

Fifteen years ago, we lived just across the river from the foot of Mt. Rubidoux. It filled the window in our dining room where the only piece of furniture was an antique bench I used as a stand for my CD player and candle. It was the perfect place to practice yoga, or watch hikers snake their way along widely spaced switchbacks to the mountain’s peak. The top of the five-foot plastic Little Tikes cube jungle gym in our back yard also provided a great view of the Mt. Rubidoux. Quentin would climb up there to watch people hike straight up the mountain, cutting the switchbacks. “Mama, can we do that?” he’d asked. “Yes,” I’d say, “one day.”

That one day was an early morning in August, not too long after Quentin’s fifth birthday. The two of us climbed the direct route up the mountain for the first time. The path was steep, and the dirt underfoot loose and dry. We turned to face each other and sidestepped up the mountain to maintain our footing, bypassing every opportunity to rejoin the main trail until we reached the pavement walkway to the summit. I lifted him up onto the walkway and followed in a single high step. I caught sight of his cheek-splitting smile before he turned and ran-hopped ahead of me to the top.

It can be difficult to understand why we climb mountains. Consummate mountaineers still rely on George Mallory’s response to the New York Times in 1924: “Because it’s there.” Contemporary research by economists and psychologists suggests that climbers and mountaineers are motivated both by reason and emotion. Calculations based on ability, financial resources, available time, and proximity to crags and mountain peaks contribute to their decision-making, but so do their desires to achieve goals and glory, master skills, and find greater meaning in life. Renowned behavioral economist and former mountaineer George Lowenstein argues that the extraordinary value frequently attached to these non-consumption goods can lead outdoor enthusiasts to take life-threatening risks.

Mount Assiniboine, British Columbia

Lowenstein speaks from experience. He nearly killed his wife, Donna, on Mt. Assiniboine in the Canadian Rockies. Lowenstein and Donna reached the summit in a white-out, but wandered off-route on the way down and had to descend a nearly vertical face in a fierce storm that dumped so much snow it was like an “avalanche.”

“I was short-roping my wife and kicking steps and we were rappelling off things we shouldn’t have trusted, like blocks of ice sticking out of the slope. Donna kept saying, ‘I don’t want to rappel off that thing, I don’t think it’s going to hold.’ And I’d say, ‘Don’t worry, it’s going to hold. Clip in and go or we’re going to be in trouble.’ I didn’t want to say ‘die,’ though I was convinced we were going to.”

Though Lowenstein admits such experiences can shape character like nothing else, the associated risks can be unconscionable. Maria Strydom’s death on Mt. Everest last month, the fifth so far this year, is a case in point. Exhausted and suffering from altitude sickness, Strydom stopped less than fifteen minutes from the peak and urged her husband to continue without her. She died in his arms before the couple could descend.

No wonder Lowenstein stopped climbing when he and Donna became parents.

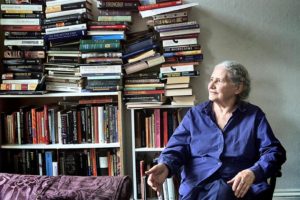

Doris Lessing, 1919-2013

Of course, the physical and psychic challenges of writing are rarely as epic as those widely faced climbing in the Himalayas, Alps, or Andes. Yet writing is hard. Mountaineer Joe Simpson’s admittedly understated characterization of his travails in the Alps as “harshly uncomfortable, miserable, and exhausting” could describe the writing experience. The Nobel Prize winning author Doris Lessing told the New York Times in 1984 that “writing is hard work…you have to give up a great deal of life, your personal life, to be a writer.” Ann Patchett refers to writing as a “miserable, awful business.” And George Orwell regarded writing as a “horrible, exhausting struggle.”

Why we write can be as incomprehensible as mountain climbing. Writers endure sometimes steep and extended learning curves, expend time and resources they cannot easily afford, and isolate themselves from friends and family to hunch over their desks, alone but for the writing implements and sustenance essential to their work. Why? For many of the same reasons some climb mountains: To create, or achieve some other writerly goal. To make a mark, lend one’s name and words to the history of literature and art. To indulge in a practice at which they excel or can anticipate gaining mastery. To discover or bring meaning to life, though it may not be their own. To achieve a goal, design and enact a plan to fulfill a personal or collective intention.

Mountains are intimidating. Climbing mountains represents a formidable goal for many, which requires intense desire, careful preparation, and unflagging commitment. This much is also true for writing. Like climbers and mountaineers, writers are often compelled to abandon secure livelihoods in pursuit of physical and creative freedom. The “starving artist” and “dirtbag climber” both embody the ideal sacrifice of material success to focus on art or the development of athletic prowess.

Indeed, the time and practice required for mastery, and the attendant threat of failure supports a wide range of comparisons between writing and endurance or extreme sports. Writers face rejection the way climbers practice falling. And even the most seasoned mountaineers routinely turn back due to foul weather and other dangers. Jon Krakauer, whose account of the 1996 Mount Everest storm is the subject of Into Thin Air, once said that detailed outlines sustain his effort to complete a book project the way that climbing “pitches” the length of a rope render long or difficult climbs manageable.

Location, and time and financial resources to sustain presence in situ, are also essential to successful mountain climbing and writing. Virginia Woolf famously argued that a woman, “must have money and a room of her own” to write, much as renowned free soloist Alex Honnold underscores the need to stay in Yosemite, whatever the financial consequences, to master its towering granite walls. In both cases, an extended presence in a physical or geographical space engenders the freedom necessary to craft creative solutions to problems.

Sunset, JMT. Photo credit: Eric Leifer

Writer and naturalist John Muir embodied both worlds. Although he lived and work in Yosemite for just six years, Muir spent most of the forty years that followed advocating for environmental preservation and national parks. His life’s work included the composition of a dozen books and hundreds of articles as well as thousands of miles trekking in the Sierras and elsewhere in the Americas.

Muir is memorialized in an epic 215-mile trail that bears his name. The John Muir Trail (JMT) originates in Yosemite National Park, continuing southeast through the Ansel Adams Wilderness and Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, to Mt. Whitney Peak. I first hiked the JMT during a family vacation in the 1970s. Along with dozens of other visitors to the Yosemite Valley that summer, we followed the JMT to the Mist Trail, which includes 600 granite stairs, slippery from the spray from Vernal Fall, to reconnect with the JMT back to the Valley floor.

Child climbing Mt. Rubidoux. Photo credit: Brohammas

I remember my then five-year-old brother Craig looking back over his shoulder with a wide grin as he raced ahead of us up the stairs with an unsteady, hand-foot matching gait. I recalled that image thirty years later as I followed my youngest child, Olivia, up the same steep trail to the Mt. Rubidoux summit that Quentin and I once hiked. Fearless, she sunk her fingers into the dirt, then scrambled her feet forward like an inch worm to meet her hands, generating a wake of choking dust as she progressed upward.

Olivia’s concentration and physical exertion as she climbed, and her triumphant smile when she reached the top illustrate the truth that a summit’s measure is not limited to elevation. It’s about “obsession,” according Jimmy Chin, who, along with fellow climber and filmmaker, Renan Ozturk, and famed mountaineer Conrad Anker, is credited with the First Ascent of Mt. Meru in 2011, via the difficult and dangerous Shark’s Fin Route. The 2015 film Meru documents this ascent, including the trio’s failed initial attempt at the summit in 2008. About their decision to return, Chin explained, “I was honestly inspired by the mountain. Inspired by what it pushed me to do. I saw what we could do better.”

Similarly, the value of a writer’s work exceeds the simple calculus of pages and publication venue. The writer is inspired by the image of what she’d like to compose and challenged to master the elements of craft necessary to bridge the gap between blank page and finished manuscript. Philosopher Michael Carter argues that this creative impulse is the “beginning” of writing, “one of the most powerful and accessible ways we have of heightening our consciousness of being creative and thus becoming full participants in creation.”

Carter’s insight rings true for me. Why exactly I am writing is sometimes unclear when I begin a piece, much as the real reasons for tackling a challenging climb can be once I’m actually standing at the base of an imposing cliff. Their meanings lie waiting in the act of writing, the climbing itself.

Works Cited

Carter, Michael. Where Writing Begins: A Postmodern Reconstruction. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003.

Honnold, Alex. Alone on the Wall. New York: W. W. Norton, 2015.

Lowenstein, George. “Because It Is There: The Challenge of Mountaineering…for Utility Theory.” Kyklos 52, 3 (1999): 315-344.

Patchett, Ann. This is the Story of a Happy Marriage. New York: Harper Perennial, 2014.

Simpson, Joe. This Game of Ghosts. Seattle: Mountaineers, 1993.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. Eastford, CT: Martino’s Fine Books, 2012.

Juliann Allison is a feminist scholar, environmentalist, homeschool advocate, yogini, runner, rockclimber, mate, and mother of four with a passion for the outdoors. She is Associate Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies and Public Policy at UC Riverside, and an MFA student at Antioch University Los Angeles.