Aminah Mae Safi, Author

Aminah Mae Safi likes to say she was raised in Texas but came of age in Los Angeles. You might not guess that she code-switches into a southern twang when she returns home, that she loves rock n’ roll, classical music, and everything in between, or that she grew up speaking English, Arabic, Spanish, and French. What you might notice is that she lights up in the classroom, the passion for her storytelling craft runs deep, and her knowledge spans the creative and academic. She’s an author, a critical thinker, a mentor, a rom-com enthusiast, a Beyoncé fan, and she’s on a mission to make Young Adult literature more inclusive. I caught up with her in December to talk Gilmore Girls, writing advice, and her forth-coming project set to hit shelves in June, This Is All Your Fault.

Aminah Mae Safi likes to say she was raised in Texas but came of age in Los Angeles. You might not guess that she code-switches into a southern twang when she returns home, that she loves rock n’ roll, classical music, and everything in between, or that she grew up speaking English, Arabic, Spanish, and French. What you might notice is that she lights up in the classroom, the passion for her storytelling craft runs deep, and her knowledge spans the creative and academic. She’s an author, a critical thinker, a mentor, a rom-com enthusiast, a Beyoncé fan, and she’s on a mission to make Young Adult literature more inclusive. I caught up with her in December to talk Gilmore Girls, writing advice, and her forth-coming project set to hit shelves in June, This Is All Your Fault.

Regan Humphrey: When did you first start writing?

Aminah Mae Safi: I started the book that became my first book, which is Not the Girls You’re Looking For, in grad school. Back then, I was actually in grad school to be a professor—I thought I was going to be doing academic writing. I started this book for myself. I didn’t see anything like it in the world. So I kept re-working it and learning about writing, and learning about craft and novels, learning about how to query and pitch. It took about five and a half years to find my agent, and then it sold and was published eighteen months later. Writing that book and taking myself seriously as a write, it was really seven years. But I come from a family of storytellers and my grandfather, my dad, and my aunts are always telling stories, and I think that’s kind of embedded in my DNA.

RH: What was it like growing up Muslim-American in Houston, TX, in the ‘90s?

AMS: You know it’s funny. I had a very strong sense of being proud of being Muslim, being proud of my culture. I was an outgoing kid and I wanted to share. It never bothered me if someone had questions because then I had questions for them, and it felt like engaging in a discussion. It was really that moment after 9/11 that it became very clear that things would be different. My dad was really clear with me. He told me people would hate me because I was Muslim. I think he did a really good job at making sure I was proud of who I was, and that thing that someone hated in me, it was not something that I should be ashamed of. That’s on them, right? What was really hard for me after 9/11 was that the people that bullied me for being Muslim were people who had been my friends. People I knew well carried Islamophobia in their hearts. It’s one reason why I wrote Not the Girls You’re Looking For. For me, it feels like this gift that speaks to so many different cultures, right? My mom is Mexican, her father is from Mexico. Her mom is a German-Texan. My dad is from Iraq. I just grew up understanding that there is one more than one way to live and one way to be. I think as a child there are times when you feel this immense weight of “I don’t fit anywhere.” But I think I was lucky that it was Houston in the ‘90s. Houston is a very diverse city; there were plenty of other kids who were mixed; perhaps not exactly my mixture, but they were, they existed. I wasn’t alone in that. That’s why I think fiction is so important and powerful because it gives you a space to not feel alone, and to not feel alone in that story. I think that’s what we all want—to know that we’re not these strange alien beings that have never existed before. I also think that was why I was drawn to history. It was to look back and know that people like me had existed before I existed. Because that’s true. Sometimes, we just pretend like it wasn’t, or we paper over it, pretending it’s always been the way we see it, and that’s not true.

RH: You originally wanted to become an art history professor. What was it like to have loved and gotten a degree in that field, only to discover you wanted to be a writer instead?

AMS: I think it was a huge leap of faith. I think that there’s always a risk in choosing art, and I think finding the ways in which you’re prepared to take those risks is really important. We don’t talk enough about it. Now, I’m lucky enough to work full time, but I’m also married. I have a partner. My income is enough to live on but the way you get paid in books is really different from getting paid every two weeks. Finding where your balance is—it’s gonna change throughout your life. There will be times when you have to work more at that day job than on your creation, and sometimes, you’ll have more room to create and work less. You go back and forth between negotiating how you’re making your art and how you’re living and putting food on the table.

RH: What was it like being a woman of color and navigating the publishing system?

AMS: I got a phone call from my editor, and she said they had already talked in-house about covers for my book. They already understood that it was important to be respectful of skin tone and hair and all of these things. I wasn’t the one who had to have that conversation and that’s why I feel that I stand on the shoulders of giants who did all of this work that I got to reap the benefit of. I think I’m also really lucky in that when I debuted, there were many other Muslim authors that debuted too. It was so wonderful to not be alone in that, and to not be the only Muslim woman. And to look behind me and see even more Muslim women coming in, and even more women of color succeeding. You’re seeing all these women being able to be at the top of their game and to produce work that people are responding to. It’s really heartening.

We tend to give cisgendered heterosexual white males the benefit of the doubt in their perspective. Readers are more likely to forgive those characters for screwing up than they are a young Muslim girl of color.

RH: Did you feel any doubt about putting out Not the Girls You’re Looking For? Was there a fear in you because of the uniqueness of the work, that it might not be well received?

AMS: Yes, of course. We tend to give cisgendered heterosexual white males the benefit of the doubt in their perspective. Readers are more likely to forgive those characters for screwing up than they are a young Muslim girl of color. That’s unfortunately the unconscious bias many people bring to the table when they’re reading. You feel protective of your characters because you know they’re not necessarily always getting a fair shake. But ultimately, I put Lulu, Sana, and Rachel out into the world to help with that. And I don’t get to decide if I’m a tiny crack that forms or if I’m the one that gets to bust through the whole bias. Sometimes you’re just the person that gets the first tap at it and it doesn’t sink in all the way. And I don’t get to control that. But I do get to control the work. I do get to say these are the characters whose perspectives I think are valid, these are the women that I want to see more of in the world. I don’t get to control what the reader brings to the table. How they receive the work. How they talk about it. That’s out of my hands. Maybe not everyone loves every character that I’ve written but if I’ve made at least one person feel like they’re not some alien in human skin, then I’ve done my job. Putting people like myself on the page, allowing them to be human and imperfect, to solve their own problems, make their own messes and come back from them? It’s really important to me.

RH: I understand you spoke four languages growing up. How did having those languages influence your storytelling?

AMS: I think that knowing a lot of languages, especially as a child, makes you understand the playfulness of language. There’s always more than one way to say a thing. That’s why I put untranslated words in fiction because I genuinely believe that if I do my job right, readers can fill in and understand without looking it up. We’re always translating what other people are saying on some level.

RH: Speaking of influences, let’s talk about Gilmore Girls. Your second book is an ode to Paris and Rory.

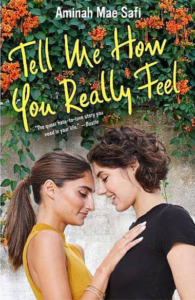

AMS: That’s right. Tell Me How You Really Feel is two girls on opposite sides of the social scale working together to make a movie and working very hard not to fall in love. It’s my love letter to Los Angeles and it’s my Paris and Rory ship of my dreams. I love two ambitious girls going toe-to-toe. I love enemies-to-lovers. They push each other to be the best versions of themselves. They stick with each other through seven seasons and a revival. They live together.

AMS: That’s right. Tell Me How You Really Feel is two girls on opposite sides of the social scale working together to make a movie and working very hard not to fall in love. It’s my love letter to Los Angeles and it’s my Paris and Rory ship of my dreams. I love two ambitious girls going toe-to-toe. I love enemies-to-lovers. They push each other to be the best versions of themselves. They stick with each other through seven seasons and a revival. They live together.

RH: It’s deeply gay.

AMS: Yeah! It’s true love. That’s true love. It just is. I grew up watching that. And this is something—and this is why I mentioned that one of my influences was Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neal Hurston and Persuasion by Jane Austen and Northanger Abbey. I love family politics and family drama. I love people finding their identities within themselves and their relationships around them. I love a good sense of comedy and voice. And I think Gilmore Girls has so much of that. I just wanted to make it gayer and inject more living, breathing inclusivity and diversity into it.

RH: Do you identify on the LGBTQ spectrum?

AMS: I don’t. But we live in a world where there are so many people living their lives and finding their happiness and their own ways to live. That is what I see around me and that is what I want my fiction to reflect. You know? My world and my friends are not all straight. And they are not all of one gender identity. And I don’t want to live in a fictional world where there’s only one of someone like me. And the whole rest of the world is white. Or the whole rest of the world is straight. I think that that is doing such a disservice to the beautiful rich tapestry of humanity. I do often have queer characters because people are queer. Right? There’s so much more than just one type of person.

RH: How did you come up with the inspiration for this Tell Me How You Really Feel?

AMS: I love rom-coms. I love teen movies. I really, really wanted a classic rom-com between two girls in a way that I’ve never seen. I didn’t feel like it was my place to write about struggling to come out. I did feel like I could speak to the idea that there are two girls of color who are able to live in their cultures and be who they are. Like there are all of these stories where the only reason why the two female leads don’t fall in love is because of homophobia and heteronormativity. Bring It On still haunts me. Bend It Like Beckham, same thing. I just wanted that classic fun rom-com where people get to explore the pieces of themselves that aren’t necessarily questioning their sexual identity. Those stories are so valid and need to exist. I feel the same way about writing Muslim girls. I want them to be able to be carefree, to normalize that their experience is not always about having to deal with Islamophobia. It’s not that they never deal with it or that it never comes up. It’s just that the core narrative of their story is not struggling with culture. With Tell Me How You Really Feel, I wanted a narrative where the core was not struggling with queerness. I don’t think I can speak to that.

RH: How do you incorporate spirituality and religion into your work, your characters?

AMS: I always root it in the character. I always try to think about what their relationship to their faith is. How they practice it. How they move through the world. I just try to listen to them about that and understand who they are in that way. Like Sana is a little more religious than Lulu is. Just to be able to see it, these moments where faith pops up—the book is not about God or religion, but these moments happen for people who do believe, and people who believe things we don’t often get to see. And I think that’s also part of normalizing different identities. People who are able to find empowerment in talking about these issues and putting them into fiction are absolutely stunning and beautiful. These stories that are so often whitewashed, straight-washed, man-washed, ability-washed—making stories that normalize the everyday, that are injected with inclusivity. That’s my mission statement. That’s what I believe I do well.

RH: Let’s talk about your forthcoming book! What was it like conceptualizing This is All Your Fault? How does your process as a writer kind of start?

AMS: In This Is All Your Fault, I really wanted that just-one-day structure. I wanted to start with the initial formation of a girl gang. Where they all see each other in a very specific way and think that they should not belong together. And I wanted to find that common goal, like if they had it—they all want to save the bookstore— then they have to work together. They have to start listening to each other and they have to break out of their ideas about tribalism and form this other group, this other tribe that is their own. I love books about complicated young women and friendship, and the ways in which we fall in love with our friends. When you have so much tokenism in media, you don’t get to see women making friendships because there’s only one woman. You never get to see the other women she’s friends with because it’s not part of the story. It’s off-screen. It’s off-page. There are so many great books out there, making female friendship the center of a story right now. And I just want to see more of that because it’s my favorite.

RH: How do you think the young women you’ve written would describe you?

AMS: Wow. Lulu would probably see me as a trying-too-hard old lady. Let’s see. Sana would probably treat me like an auntie. And Rachel would ask me to get out of the way already, because she’s trying to line up a shot. Rinn would probably ask me if she could interview me. She’s a bookstagrammer. Imogen would probably do that thing that teenagers love to do, that cat thing, where they’re like, I don’t want to talk to you, but I’ll sit next to you. That is Imogen for sure. And Daniella would just start firing off really challenging questions, because she loves to rattle authority. And she would see me as an authority figure, and she wouldn’t like it.

RH: We talked a lot about your Muslim identity growing up. We didn’t talk much about your Mexican-American identity.

AMS: I think it’s because it’s more complicated. My mom is from that generation where they were taught to assimilate—have a white name, marry a white man. She grew up in Dallas in the fifties and sixties. For me, I think growing up in Texas helped. There’s a very visible and culturally strong Mexican-American population. It feels a part of me. But it is a different narrative because of the way it was transmitted—my mom had to reclaim her culture and try to teach that reclamation to me. It wasn’t linear: this is mine and now it’s yours. It was very much: this was mine and it was taken from me and I tried to find all the pieces that I could and now I’m handing them to you.

RH: If someone summed up Aminah Mae Safi—what makes you who you are, what makes you so valuable in this world, this time we’re in right now—what would they say?

AMS: I hope they would say… that I write real authentic young women. I hope they say I’m a little bit outrageous!

RH: What’s your advice to up-and-coming writers?

AMS: Okay, so I would say, number one: start. Number two: finish the fucking thing. Even if you don’t think it’s good, just finishing that first thing will teach you so much. Number three: Batshit self-belief. You have to believe in yourself, more than anyone else. It takes a lot to cultivate that, but you have to believe in yourself in a way no one else can. It’s not that you believe you have all the answers. Believe that you can find them. You have to believe that you can get to where you see that work going. Even if it’s hard. Even if you don’t know what you’re doing. Committing to yourself is that leap of faith. It is a radical act of self-love. It’s a radical way to move through the world—for anyone who is marginalized, you’ve been taught to not trust yourself. You have to believe you’re capable of doing things you have not seen yet. It’s the trifecta: start the thing, finish the thing, believe you can get there even if you don’t know how. And be willing to learn. That’s life.

Regan Humphrey is an award-winning writer and artist. She is an MFA candidate in YA fiction & playwriting at Antioch University. She holds a BA in creative arts, writing & performance, a BA in cross-cultural relations, and an MA in applied psychology. Her work has been published online by Poems by New Yorkers, Antioch’s Social Justice Newsletter, and Lunch Ticket, and in print by Gilded Dragonfly Books and Bard College at Simon’s Rock.