Angela Morales, Author and Essayist

The evening I interviewed powerhouse Angela Morales, the sky went iron before darkening to slate black. The tinted windows kept the rain out of a small, spare, fluorescent office, as a burgundy-wood desk stood between us. Angela has a warmth and a strength that are equal parts gentle and fierce. She lives proudly—the daughter of two generations of Mexican-Americans—and her insights about multiculturalism, creative nonfiction, and claiming one’s space resonate at the same pitch as her glowing, singing prose. Her nonfiction, which centers around her upbringing, uplifts her cultural heritage. As a teacher, mentor, mother, and great-granddaughter, as a writer constantly working on her craft, she implores us to do the same.

The evening I interviewed powerhouse Angela Morales, the sky went iron before darkening to slate black. The tinted windows kept the rain out of a small, spare, fluorescent office, as a burgundy-wood desk stood between us. Angela has a warmth and a strength that are equal parts gentle and fierce. She lives proudly—the daughter of two generations of Mexican-Americans—and her insights about multiculturalism, creative nonfiction, and claiming one’s space resonate at the same pitch as her glowing, singing prose. Her nonfiction, which centers around her upbringing, uplifts her cultural heritage. As a teacher, mentor, mother, and great-granddaughter, as a writer constantly working on her craft, she implores us to do the same.

Regan Humphrey: What was it like to grow up Mexican-American and a writer? When did you find out that writing was for you?

Angela Morales: So, I grew up here in LA. I am a third-generation Mexican-American, so I would consider myself to be pretty assimilated. I had a different view of America than my grandparents did as immigrants from Mexico. I grew up in a middle-class neighborhood. My friends were all different colors. My best friend growing up was Latvian, and her dad was pretty racist. He once said he didn’t like Mexicans. I was shocked. It made me feel like I shouldn’t go to her house anymore, but she said to me, “No, no, no! You’re okay, you’re the good kind.” That really woke me up.

In terms of becoming a writer, I didn’t know that I wanted to write until college. When I became an English major, I started reading a lot of good stuff. Then at some point, I started wondering if I could write some of that stuff too. But when I look back, I realize that I was always writing, even as a kid.

RH: How did you transition from “Can I write?” to a published essayist?

AM: It was a long journey. I went into an MFA program when I was twenty-six, and as soon as finished, I got a full-time teaching job at a community college, which basically consumed me. I really wanted to be a good teacher. I wanted to learn how to do that, and so I kind of stopped writing for a few years. It took me a long time after that to get back to writing. I don’t regret that now, because in those years of teaching, I had children and I got married. I learned a lot about life, and so when I came back to writing, I felt more confident. I felt that I had a lot more to say. Everybody has their own path with writing. Some writers are very successful at a younger age, and their flame burns brightly from the time that they’re in their twenties. And other people, their flame gathers strength as they get older. There’s no right way to be a writer.

RH: Which of your essays is your favorite?

AM: The one that’s closet to my heart is called “Nine Days of Ruth.” It’s about my grandmother’s death. I put a lot of love into it, so when I read it, I feel really happy that I was able to preserve my version of those nine days when she was dying.

RH: How do you conceptualize the purpose or the power of creative nonfiction, as a container for these very emotionally saturated moments? Where do you think the power of the personal essay comes from in capturing these really poignant moments?

AM: Nonfiction is the only genre that works for me because when I tell the truth, my writing is better. It’s like… I’m responsible for it. I want to make sure it’s clear and meaningful and thoughtful.

These older Mexican ladies can feel like their childhoods were important. Their childhoods had beauty; their childhoods are worthy of literature.

RH: How has writing creative nonfiction impacted your life?

AM: The impact has been mostly great. I think my family is really proud that our experience is being written about. So that makes me feel really good that I’ve made them proud, that these older Mexican ladies can feel like their childhoods were important. Their childhoods had beauty; their childhoods are worthy of literature. What I want to do in my future writing is to continue to tell their stories, but nonfiction comes with risks too. Like do I have the right to tell some people’s stories? Like, in the case of my father, do I have the right to say things about him that aren’t so flattering? That’s another thing that’s come up, but nobody’s complained yet.

RH: When did you discover that you wanted to teach?

AM: Well, I went to the University of Iowa for the nonfiction MFA, and my financial aid package required me to teach. So, I literally walked [into a classroom] cold. I had zero teaching experience and I walked into that classroom terrified. But little by little, I started to see that teaching was just talking about writing. The students were really kind—I think they could see my terror, and they were trying to nurture me as a teacher. It was a lovely introduction to teaching. I found out that teaching is really natural for me and it feels good and it’s a beautiful experience to be in a room full of people when you’re all thinking about the same things.

RH: What has it been like writing, teaching, and publishing from your experience as a Latina? Has it been hard at times?

AM: The hard part has been not writing to stereotypes and refusing to write what other people expect you to write. I submitted my first manuscript to a publisher who told me that it was not ethnic enough. I got feedback from another reviewer, another Mexican-American, who told me that he thought I was a fake Mexican. I didn’t really know what to make of those comments. I was torn—but, ultimately, I decided that the person they wanted wasn’t who I am. I think, to be a writer you have to write about your true experience. What you actually think and what actually happens to you. I’m very conflicted about making things Chicano literature or ethnic literature—a separate category. I really want those things to just be included in the regular canon of literature. I don’t necessarily want to teach Chicano literature. I just want to teach literature and make African-American, Asian-American writers a part of that. I don’t want to push it into a little category. On the other hand, giving special attention to those writers is important too, so I’m torn still. Do we play up those tropes in our lives or do we just ignore those things and just write from our hearts, and let that be what it is? There’s no such thing as a Mexican-American experience. We’re all different. There’s no one experience. So, I think you have to ignore that stuff in the end and just write what you feel. It’s hard.

RH: It sounds like a particularly unique challenge—you’re telling your story, but there’s also a judgement about how that story should be told. Are there multiple things you have to think about and do at once, or throw away, while you’re writing?

AM: Yes. Exactly.

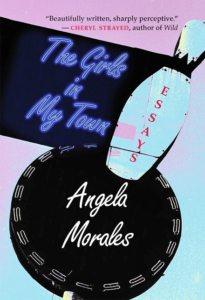

RH: You’ve published one book, The Girls in My Town, and lots of essays—have you interacted with your readers at all? And what has that been like?

RH: You’ve published one book, The Girls in My Town, and lots of essays—have you interacted with your readers at all? And what has that been like?

AM: Oh, my gosh, I’ve had so many nice emails. It’s amazing. I’ll just get like a random email from someone telling me, “Thank you for writing this.” It’s so great. I was writing this little thing, like in the library, and it connected with somebody? That’s so cool. A couple times I’ve done readings at community colleges and students will thank me for writing about domestic violence. And they’re like, “This is my family; thank you for putting that out there. I think I’m going to write about it too.” It’s like the icing on the cake. Writing is hard and we do it because we’ve got these burning stories to tell, but on the other side are our readers. It means something to them.

RH: We have a number of Latinx students in our community, here at Antioch, and it’s meant a lot to have you here, reading your work and expressing all of these beautiful, celebratory, and also real things about growing up.

AM: It’s such a pleasure to know that.

RH: Could you say more about the process of generating a personal essay?

AM: All of my essays start in my journal. I’m usually on a rant. [Laughs.] Ranting, or whether I’m haunted by a memory, or I have a sudden lightbulb thought, and then I write about it, I scribble out whatever thoughts I have. Later, I’ll look through my journal and say, “That day of ranting could be an essay!” I’ll start to type it up, but I always like to work in journal-form first. I think it’s more organic and natural. It doesn’t have the same performance pressures as writing into your laptop, where it feels like it should be more finished or polished. But in your journal, you can scribble out a bunch of thoughts. A lot of times, those feel fierier and more poetic. It might take me six months to make it finished from there, but the skeleton of it, the first draft, is always written by hand. It’s always bubbling up from a place of distress or longing or love. I want to write about something that I care about. I want to give it an affirmation. I want to paint a picture of this thing before I don’t feel it anymore or it goes away.

RH: Can you remember the first essay you ever wrote?

AM: It was called “Exhuming Abuelita”. It was a story about going to visit my great-grandma’s house, and then she died right after that visit. Her story has really intrigued me from the very beginning. I feel like she’s my muse, in a way. Her life was so hard and so bad. I feel like she’s watching me from afar. She had eleven kids. She was married when she was fourteen. Imagine having five babies by the time you’re nineteen. What a life for a woman, right? No birth control. When she was born, women couldn’t vote. She wasn’t a citizen of the United States. Our lives have these amazing contrasts.

Back in her generation, the borders were open. Mexicans could come in and out of the US pretty freely. So they lived sometimes in their town in Northern Mexico, and then they’d come on up to visit the relatives and they’d stay here for a while. At that time, Mexican-Americans felt comfortable on both sides of the borders, whereas now, you have to choose a side. Which is why we have so much illegal immigration. All that land—there are families who used to just go freely back and forth, and still do, but now they just get deported for it.

RH: I often wonder, for those with immigration histories, having those original family members who grew up in a different place can sort of compact the transition from one culture to another. It can sometimes be very stark. I grew up here and you grew up there, and therefore I am American, you are something else, but I am attached to you. How have these flavors that have been able to mingle a bit more slowly over time (since your family was able to go back and forth for a while), how has your multicultural background influenced your writing practice?

AM: I write with [Spanish], especially when I’m recreating a scene with relatives. I don’t speak it, but I hear it a lot. I hear them speaking. It wouldn’t be right to exclude it. Spanish is very much a part of my life. So, the language is something I try to make feel natural and accurate. But I have also learned in the past two years that my great grandmother was full-blooded Chiricahua Apache. Since then, my family has become very involved with this native community. It makes me think, these people aren’t immigrants at all. They’ve been here all along. I’ve become a little bit more connected to my native past. Like, actually, all Mexicans are native. That’s not something that we should ignore.

RH: What’s that like, discovering these roots you didn’t know you had?

AM: It’s fantastic. On the one hand, I tell myself I never grew up Native-American, but I feel like I understand the philosophy behind a lot of native practices. And then I ask, “Am I entitled to that?” It wasn’t a part of my growing up. Who’s entitled to certain experiences, you know? What qualifies someone as being entitled?

RH: What is your lived experience of being a writer in close proximity to others, like your children and spouse?

AM: You mean, to people who take all your time? [Laughs.] I have to fight for my time as a mother, as a writer, but my husband has been super supportive, and he encourages me to go off and work and do my thing. I can’t imagine what it would be like to have a husband—like my mom, or grandma, or aunts had—where the thought of a woman going off and doing writing would’ve been absurd to them. They would actually think that was laughable. I’m lucky. As far as having children, I know you don’t have to have children to be a good writer, but, for me, it’s given a layer of understanding about humans that I didn’t have. Just to care for another human is important. For me, it’s only added to my fears, my voice. I mean there’s something about holding a newborn baby and being responsible for it that changes your perspective on the world. Once you become a parent, you understand things on another level.

RH: I keep thinking about your great-grandmother. What does it mean for you to be living your life while holding this real awareness that, a few generations back, this woman in your family was going through these very different circumstances? How has the distance between your experiences weighed on your shoulders?

AM: It makes me not want to take things for granted. I feel very privileged to be sitting here right now at Antioch. That’s something that my grandmother could not have dreamt about. She would not have even known about a job like this. I’m very mindful of all these women who did back-breaking work in the fields, taking care of all these babies that they couldn’t take care of—I’m very mindful of the racism they encountered, them being thought of as small invisible workers, like little worker bees. I’m sensitive to that when I’m working. When I feel like someone’s ignored me in the workplace, or when someone assumes that I don’t have an education, I try not to freak out about those things, but I’m very mindful about it. Like, I earned this. Or like… we’ve been working for generations to get right here. I think any person of color has that experience. You have that feeling of I’m not worthy to be doing this. Put your head up, stand next to the white male writer who’s sixty years old, who’s published ten books, and go maybe I do belong here. I’m going to make you hear me. It’s an exercise in developing your confidence. Ultimately, those grandmothers who were working in the field, I feel like they’re standing right behind me going, “That’s right; here we are.”

RH: What a beautiful image! For writers of colors who are coming up, learning to write their stories, what is some advice you’d give them about encountering racism? When they get to the stage and there’s the stereotypical old white man writer, what do you go to within yourself to stay strong in the face of a country, a culture, that says don’t?

AM: Think of the people standing behind you. Speak for them too. Speak up. Be assertive. Here’s the bigger thing: I think if you’re a writer of color, you need to believe in your stories. Believe that your stories have value and embrace your voice, the voice of your home. Embrace the voice of your people, the voice of wherever it is you come from.

Regan Humphrey is an award-winning writer and artist. She is an MFA candidate in YA fiction & playwriting at Antioch University. She holds a BA in creative arts, writing & performance, a BA in cross-cultural relations, and an MA in applied psychology. Her work has been published online by Poems by New Yorkers, Antioch’s Social Justice Newsletter, and Lunch Ticket, and in print by Gilded Dragonfly Books and Bard College at Simon’s Rock.