At the Junction of History and Fiction: A Family Reunion

L’Improbable Café in Paris

Last summer, my brother and I met a first cousin for the very first time at a café called L’Improbable in the Marais in Paris. She shared the feminine form of my brother’s name: Frédérique. She was a journalist and arts lover, about to turn fifty. We had been playing e-mail tag for a few years as we pieced together the narrative of our disassembled family, estranged for almost seventy-five years. As the two Frederics and I sipped our drinks and laughed nervously at the unlikeliness of the rendezvous, I kept staring at her face trying to figure out which curves and lines belonged to us, and which were her own.

This past March, Frédérique and I met up a second time and walked the halls of the Salon du Livre in Paris together, embarking on the odd journey of getting to know our new-yet-old family. We conversed about books, politics, and the arts as if we had known each other our entire lives. As we passed in front of the Editions Christian Borgois, my cousin told me how, a few years prior, she had been at the Salon du Livre with a filmmaker friend. They had stopped by the editor’s stand where a display advertised a new translation of a Jim Harrison book. On a backdrop were blown-up segments of the book and up there, in large print, was my father’s name in a random extracted sentence. Jim Harrison and my father had known each other well, sharing a kitchen, sharing wine, sharing the same love for life that had animated my childhood. At the time, Frédérique had told her friend that yes, that was supposedly her half-uncle but no, she did not know him. The families had split during the Second World War. We were secrets from each other.

The seeds of our future friendship were planted when our grandfather met and married two women over the course of the war: my grandmother first, hers second. Sometimes it feels like my existence sprouted from the ashes of World War Two, as if the world before it was a blank slate, and afterwards came my family. And yet, my past is a past of the living. My immediate family all survived. Other stories carry different grief and different circumstances. For some, it’s the Holocaust. For others, it’s Algeria. Or Communism. The fall of the Berlin Wall. And now Syria. History has a way of coming from somewhere and catapulting towards nothing: wars that shape our pasts, us writing these shared traces like ants tunneling behind glass.

Nazi troops on the Champs-Elysées, 1940.

On my paternal side, Valentin, a military man, married my grandmother, Edith, at the start of the occupation, and my father was born shortly afterward in a Parisian suburb. His parents were not together long. Their divorce was finalized when he was still a toddler, and my father was sent to live with his aunts and uncles in the woods of Sologne. There was not enough food in Paris. His mother remained in the city to work. Valentin never sent another penny their way.

My father had a single, yellowed photograph of his father as a young man: a tall handsome man in his military uniform. And he remembered only one memory of him from when he was five-years-old. He carried the bitterness of his father’s desertion for a long time, and struggled in demonstrating affection. The only time my father ever told me he loved me was on his deathbed. Yet, he was a devoted father and husband, a man whose love of life was sometimes enough to make us forgive his impenetrable heart. He escaped the cataclysmic devastation of a broken home, not unscathed, but intact.

Without the facts of Valentin’s departure, my brother, mother, and I assembled our own fiction. The older generation said knowingly, “You know, it was the war.” Oblique and open to interpretation. Isn’t that how we piece history together anyway? In whispers behind my father’s back, we blamed Edith for their abandonment. We imagined Valentin as a gallant man, driven away by her bitterness. In my childhood memories, my grandmother appears like a caricature: a long, gray face matching long, gray teeth and strange metal hooks at the gum line. She would pull the fat of our cheeks and press her cheekbone hard into our faces. My brother kicked her in the shins and hid in the bushes.

Looking back, what sort of story had we built?—a sexist one, in which a spiteful woman abandoned with her child during the Nazi occupation might naturally be held responsible for her husband’s departure.

Each time she visited, my father became irascible. After cooking a large French meal, he abandoned us to mow the grass. With the drone of the mower in the background, my brother and I sat in the living room for hours, bored out of our minds as the remaining grown-ups slowly drank tiny cups of coffee. Edith took us aside to tell us how awful the winters were without her grandchildren, how she couldn’t live without us, and how terrible our parents were for not letting her see us. I had to pretend I liked the coarse pink wool sweater that she had knitted me. Why did she pick the roughest wool she could find? Yet, she had put all this time into it, knitting all winter, thinking only about us.

That was the problem. Those visits were infused with guilt, all those grown-up emotions projected upon the grandchildren: Edith trying to make us feel guilty that she never saw us, my father’s guilt about not liking his own mother, and my mother’s guilt that she couldn’t force my dad or her children to like her mother-in-law. With guilt came the unspeakable: We were never allowed to talk about Valentin.

When my father passed away from cancer in December of 2011, we published an obituary in Le Figaro. Later in my year of weird grief, I considered hiring a P.I. to help me locate the rest of his family, to piece together what happened to Valentin after 1942. We had heard rumors about half-brothers. I had nothing to go on, just my grandfather’s name and a divorce certificate. I found nothing on Google. Nobody else in my family seemed to care. Perhaps I wanted to glean more of my father, to trace his history a bit longer. I never followed through.

Six months later, a Facebook message went straight to my junk mail, and I didn’t find it for months. A newly-discovered cousin, Alexandra, had read the obituary. She had heard of my father. That contact initiated a gradual reunion that included a series of emails, an introduction to several more of the first cousins, and, eventually, the meeting with Frédérique in person in the Marais.

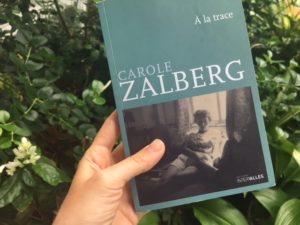

One week after Frédérique and I were at the Salon du Livre, Jim Harrison passed away. He had been a mentor of mine since my mid-twenties when my uncle had forwarded him a poem I wrote. For years afterward, we continued to send each other the occasional piece of writing. His were gems, while mine were the jagged works-in-progress of a nascent writer. Just the week before he died, my cousin and I had been in front of his editor’s stand, talking about the coincidences that had reunited our family, talking about Jim and my uncle and my father, talking about the intersections of their lives and what had brought them together all those years ago (Key West, 1970s). I bought her the French translation of Just Kids by Patti Smith, and she bought me À La Trace, a travelogue written by her friend and author, Carole Zalberg. We share tastes and perhaps the same nose.

One week after Frédérique and I were at the Salon du Livre, Jim Harrison passed away. He had been a mentor of mine since my mid-twenties when my uncle had forwarded him a poem I wrote. For years afterward, we continued to send each other the occasional piece of writing. His were gems, while mine were the jagged works-in-progress of a nascent writer. Just the week before he died, my cousin and I had been in front of his editor’s stand, talking about the coincidences that had reunited our family, talking about Jim and my uncle and my father, talking about the intersections of their lives and what had brought them together all those years ago (Key West, 1970s). I bought her the French translation of Just Kids by Patti Smith, and she bought me À La Trace, a travelogue written by her friend and author, Carole Zalberg. We share tastes and perhaps the same nose.

These last years have brought tragic losses to my family: deaths, divorces, disappearances, injuries, and illness. At times, my life feels like it is narrowing. At times, I find it hard to breathe. Am I turning inwards on myself, becoming so small that nothing will remain? And yet, I have a whole new family, seventy-five years after a war.

Frédérique told me more about Valentin. She filled in the facts where my family had let our imaginations run wild. He was a gambler, a womanizer, and a spendthrift. He lied about their social position. Frédérique’s grandmother, his second wife, cleaned houses to have enough money to feed the four children, despite Valentin’s military pension. Their childhood was hard. There were ashes there, too. We have posthumously absolved my grandmother, Edith, not of her bitterness, but of her complicity. Too little, too late, and there is no absolution for what we whispered all those years behind her back. But stories are neither stable nor straight. They are crooked and damaged and brilliant. And they do not end; we are connected to each other beyond what we immediately know, our pasts constantly retrofitted to meet the present, blossoming or shrinking depending on perspective.

Diana Odasso is currently an MFA student at Antioch University Los Angeles and Managing Editor for Lunch Ticket. She previously served as Lunch Ticket’s Translation co-editor, and has translated French literary texts to English (published in Jim Harrison’s The Raw and Uncooked), ghostwritten for an autobiography, and blogged for the Huffington Post. She lives in South Florida with her two young boys and Boston Terrier.