Awakening the Unconscious Legacy [trigger warning]

I dreamt I was a sex slave. One of many, though I couldn’t talk to the others. And every night there was a faceless entity pushing down on me, forcing himself inside of me.

I dreamt I was a sex slave. One of many, though I couldn’t talk to the others. And every night there was a faceless entity pushing down on me, forcing himself inside of me.

When I woke up, the terror was still there, a tidal wave waiting to crash until my dog licked me to take him out, and the feeling dissipated completely.

Later, while doing my dance of writing, then pacing, then writing, then pacing, my friend texted me to discuss an essay I sent her about a woman’s life of trauma. While we texted back-and-forth about the essay, she apologized to me. I asked why. She said she’s having a funky day from the nightmares she had the night before. I told her apology wasn’t necessary and that I had nightmares too.

“It was scary,” I said. “Maybe it was from an NPR story I heard a couple of weeks ago that’s been stuck in my head.”

I know what trembling presence feels like. A gift man thinks is to his kind. The curse of being born to bodies like mine. I know what it means to strengthen the spine. To lift the weight from solid feet to carry the presence from the bones. Writing wakes the rage fueled by the ever-presence in synapses. Writing makes you sit with senses, with firing synapses forming words, finding space on a blank page. Words hold space. Vibrations. Tones. Waves. Vibrating to the bone. Shaking the core. A taser. Clipped to skin. Electric.

I thought that was why I trembled. I thought wading in memories until words took shape must have sent the shock to my unconscious mind making words perform while I slept. Then, something told me that it wasn’t a memory but a haunting. The ghost of an unconscious legacy, and I didn’t know what he wanted yet.

So, I pushed the ghost aside, and my friend and I casually comforted each other through silly memes and gifs. We chatted about her recent publication and Pushcart nomination. I could hardly contain my enthusiasm for her.

“Yes, it’s very exciting, and I’m honored,” she said, “but no one tells you when you write a rape story, every woman wants to share theirs with you.”

I thought about my recent difficulty with putting myself back in harm’s way to write about my past experiences with boys and men who take up their rite of abuse. I saw my writing as an act of resistance; with my broken bones healed, I could carry the weight of his (of every his) presence. I hoped writing my resistance would inspire others. But I, like my friend, never thought sharing my story would mean sharing their weight.

I listened as she shared stories, but none of the burden; she only held me there for a minute before she shocked me out of it with her twisted humor. Somehow she knew—perhaps from years of service to her community or years of carrying weight that could crush most others—how to carry on with the weight of hers and theirs.

When we got off the phone, I got a text from a friend inviting me to see the keynote speaker at the White Privilege Symposium. A few hours later, I met my friend at the Symposium. We sat down at an empty table as one of introductory speakers began. Their thought-provoking performance put me back in the space of deconstructing white supremacy. In my writing, I put focusing on whiteness aside to bear witness to my experiences as a woman—at the time, I hadn’t quite connected how they intersected.

They introduced the keynote, and I felt the presence of the ghost.

_____

I have felt unwanted fingers slip in while sleeping, waking me to the nightmare of fighting off a boy I thought was my friend. Each time I straddle my legs in stirrups at the gynecologist, anxiety emanates as I’m forced to put blind faith in the hands of the figure in the white lab coat. Many women know this feeling. For this reason, I choose to make my appointments with women.

This appointment, an insertion of an IUD. A nurse asked me how long ago I took ibuprofen. Was I supposed to? I never saw the emailed instructions to prepare for the pain. I started to panic slightly. She told me not to worry; she’d get me some ibuprofen, and the doctor could give me time for it to kick in.

Less than five minutes later, a white middle-aged woman entered. Of course the one time I want the doctor to take her time, she doesn’t. I asked the doctor if she thought I needed more time for the pain medication to kick in. She assured me I didn’t have to worry and that it was a “quick and easy” procedure. I laid back, saddled up to the stirrups, and tried to relax. A quick insertion to keep me—us—worry-free. I have a high tolerance for pain.

Photo Credit: Brittany Horrigan

“This will feel a little cold,” she said inserting the speculum. “This will feel a bit uncomfortable,” as if the proclamation would push any anxiety away. I felt her poking and prodding, fishing around in me. And with it, excruciating pain.

“You have a small cervix. You haven’t had any children?” She asked.

“No.” I was in too much agony to be offended by the assumption that my age meant I had.

“Ah. Here we go. Okay, you’ll feel a little pinch.”

Pinch? Pinch is what your mom does when she wants you to pay attention in church. “Pinch” in this case was a razor-sharp instrument clasping my skin, pulling off all the skin on my body. Except this wasn’t happening outside of my body. It was happening within.

“All set,” she said, rolling back her chair indicating I could free myself from the stirrups. “Sit up slowly.”

She pulled off her latex gloves, handed me a pamphlet, and mumbled instructions. But all I heard was a throbbing, a ringing, resonating throughout my body. Clearly, she had no clue how much I was suffering. Or maybe she did and had forced herself to numb the empathy. How else could she routinely perform procedural pain?

Ringing. A call. For me to answer and shout, “I’m in pain!” But I didn’t. I stayed mute. Like we often do. I stayed mute and said, “Thank you.”

She told me to take my time before leaving, but all I wanted was to get the fuck out of there. I put on my clothes, and while slightly hunched, pressing one arm to my lower abdomen, headed to the line to pick up my other prescriptions.

Oh my god. Please hurry. Fuck. Fucking terrible health insurance too cheap to give the actual care you need.

I clenched my teeth and pressed a little harder. Fuck! The line shuffled steps forward, and I began to sweat profusely. It was winter, and I started to de-layer. Two more people. Please hurry! I reached the counter, and the woman asked for my medical ID card. I moved my arm to grab my wallet, but my hands were claws. My fingers wouldn’t bend or open, and suddenly, I felt faint. I felt my white face get whiter. “Excuse me,” I said and stumbled over to a chair a few feet away. I looked at my feet to ignore the people staring at me.

Somehow, I drove to meet my partner halfway and laid in the fetal position on the passenger side until we reached home.

_____

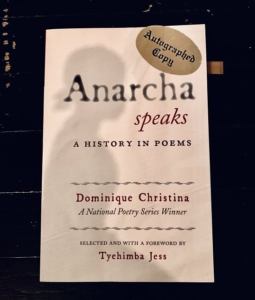

Years later, I remembered my IUD experience when a story on NPR struck me. The host introduced Denver poet Dominique Christina’s latest book about “Dr. J. Marion Sims, a white doctor considered to be the ‘father of modern gynecology,’” who in the 1800s “experimented on enslaved black women” to discover new procedures for white women.

Christina wrote the book from the perspectives of Dr. Sims and one of the slaves, Anarcha. She introduced a poem from Sims’s perspective, “Dr. Sims Makes Something New,” by explaining how without giving Anarcha any anesthesia—white people conveniently believed that blacks had a different threshold for pain—he used Anarcha’s body to invent the modern-day speculum, an instrument used for gynecological exams:

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

She is so easily disassembled.

I take the ruined stock of Eve,

The wilted petals, the spent flesh,

And bring it wire, steel.

Restoration.

Everything we delight in came

First by the blood of a woman . . .

I sat in my car in front of my house frozen, listening. To Sims, Anarcha wasn’t a person, but an open wound to stitch and tear and torture, again and again (thirty times) until his fingers found the right moves, hands ready to repair wounded white women.

Then, Christina read “No Magic, No How” from Anarcha’s perspective:

. . . . . . . . . . . .

blood and shit

Massa-Doctor’s prayer less ness

what i gotta do Jesus to

get out myself?

huh?

what i gotta do to

junk this here body.

tell me quick lawd.

i’m listenin

i’s ready . . .

But Anarcha was not just an open wound; she was somebody. Somebody who desperately wanted to escape the body being tortured by a body whose brutality will be justified, by a body who will be memorialized by a body of citizens seduced by convenient truths. When the segment ended, I went inside, and Anarcha followed. She haunted me. But I had work to do, so I put my thoughts and feelings to rest. But the thing about ghosts is, what we can’t see doesn’t disturb their presence.

_____

As Dominique Christina walked up to the Symposium stage, I realized she was the poet I heard on NPR weeks before.

“This is an invitation for you to be in your body, to risk feeling everything,” Christina said.

I felt the “pinch;” I felt the forced fingers.

However, in dreams, all of the characters are you. I remembered that I was not just the slave, but also the faceless entity. This time, when the poet read, the skin that cut into Anarcha’s was mine. Everything we delight in came / First by the blood of a woman. It was my choice to let her bleed for white women—for us.

And with it, a new sense not just of what it felt like to be subject to terror, but what it feels like to terrorize—the unconscious legacy of white supremacy buried within.

“Memory is a persistent ancestor; it hangs onto the marrow.”

I don’t know how dreams work, how they grab at feelings buried in synapses. But this was a seance. Dominique Christina a medium. Anarcha’s and Sims’s ghosts hovered until striking. Vibrations. Tones. Waves. Vibrating to the bone. Shaking the core. A taser. Clipped to skin. Electric.

Stunned. Frozen by the waves of words projected, rocketed, shot at me. I was motionless. Without words. I was only with what haunts me: the shudder of lives we terrorize(d). A resuscitated reckoning that white folks must perform.

Pictured: Dominique Christina

Photo Credit: Dominique Christina

Dominique Christina pinched a nerve in me to wake the unconscious legacy of white supremacy and the pain that radiates. As she read and spoke, I knew that Anarcha didn’t choose to subject herself to torture for white people like my partner and me.

“You are a concept, but from the moment you arrive, you are given a construct.”

Christina made me confront the fact that if I decide to have a child when I take the IUD out, I can do so because of what Anarcha and the other slaves were forced to endure. My blood birthed from theirs. Every child is/was born from the torture white people inflict. Every white and black child is a memory. Black children are born with the pride and the pain. White children are born with the guilt and the shame. Black children learn to reckon with and resist it. White children learn to ignore it. But shame and guilt carry weight too. Although white folks have gotten good at putting it back on people of color to carry and have taken the rest and buried it, the ghost of our legacy refuses to leave. He meets us in our dreams.

“I really do engage memory as a radical act. I really do like to re-member, which is to say, I’m trying to integrate the stories back into my body.”

Christina makes sure we remember the pain and not just the science. We live in an open wound. Amnesia cannot dam the blood from spilling. I, as a woman with all other women, suffer living in this oppressive patriarchy, but I, as a white person with all other white people, am trained to ignore how the systems in place benefit white people. Subversion, dismantling the systems that benefit white people, is the only way to mend our wounds and heal. For a white person, resistance without recognition of her place in history denies what haunts her.

What I inherited brings me sorrow, yet avoiding the ghost of white supremacy solidifies his power. To haunt is to inhibit, to reside, to remain. Christina uncloaked the ghost of white supremacy, the whiteness occupying our bodies—he has moved and morphed as we have. I now see that before I can exorcise him and embrace the spirit of resistance, I must understand his presence, his terror, his shape-shifting ability. The unconscious legacy that lives in me doesn’t make me a bad person; this is not a matter of good or bad, but of learning to use eyes. I work to shift his position to my conscious, so I have the perspective needed to examine my place in the space whiteness possesses. I work to move my body, so Anarcha, Christina, and all of the resistance have the space to lead.

Kate Carmody is a writer, teacher, and activist. She is currently working on her MFA at Antioch University in Los Angeles. At Lunch Ticket, she is a blogger and a member of the community outreach team. Her writing is forthcoming in Stain’d Arts. She lives in Denver, Colorado with her fiancé and dog, Corky St. Clair. Twitter: @KateCarmody8

Kate Carmody is a writer, teacher, and activist. She is currently working on her MFA at Antioch University in Los Angeles. At Lunch Ticket, she is a blogger and a member of the community outreach team. Her writing is forthcoming in Stain’d Arts. She lives in Denver, Colorado with her fiancé and dog, Corky St. Clair. Twitter: @KateCarmody8