Becoming a Wordplay M.A.S.T.E.R. (Maker of All Sorts of Tomfoolery to Entertain Readers)

Photo Credit: freepix.com

Like any young teenager, I was passionate about the things I loved and the things I hated.

What I loved were my pets, which came in all varieties (dogs, cats, ducks, guinea pigs, birds), my funny storybooks that featured dorky kids like me (too tall, clumsy, self-conscious), and my writing, especially the comical stories I composed with my best friend Izzi (which we crammed full of wordplay).

What I hated were stewed tomatoes (creamed green beans took a close second), chores of any kind (but especially ones that required hair removal), and my sisters hogging the only bathroom in our small, three-bedroom house (which was perpetually overrun by my pets, my parents, four siblings, a granddad with dementia, and long-staying friends).

What did wordplay have to do with all this?

Photo Credit: freepik.com

It was my mind’s way of balancing hardship with joy.

When my parents weren’t swearing up a storm or swinging the switch to curtail the chaos, they were shifting much of the family responsibility to us three oldest girls (I was third in line). My mom was in pain every single second from a car accident, and my overworked father was mostly absent. Granddad couldn’t remember our names, or where he put his dentures.

For me, reading and writing verbal wit was pleasurable. As a reader, I loved how wordplay called attention to a text’s letters, words, phrases, sounds, and meanings. This made stories funnier, and when I detected alternative meanings and deciphered riddles, I felt challenged, smarter, and empowered. When I was writing, I found that adding all kinds of silly, clichéd, exaggerated, jumbled, and cryptic text kept me immersed, intrigued, and smiling.

I didn’t just like wordplay; I NEEDED IT. Because most of the time, I felt like pulling out my hair from all the noise, confusion, arguing, and mess.

My friend, Izzi, had her own drama and challenges, and together we latched onto writing with wordplay as a way of coping with our circumstances. By creating and escaping to places we loved, we became anchored, balanced, safe. It worked like magic.

***

I’m now a children’s/YA writer, and I work hard to incorporate wordplay into my stories because it’s still comforting. To romp in landscapes overgrown with wordplay is a cheering thing. I dig deep into my memories to recall childhood events and then reshape them into humorous scenes. Let me show you an overblown example of wordplay at work.

Photo Credit: Kevin Laminto/Unsplash

Suppose I decided to write a scene in which my older sister is once again monopolizing the bathroom while she primes herself for a date.

Whenever she did that, I was perturbed not only because I had to wait, but also because, apart from being smaller and smarter than me, she was way prettier. When she’d finally open the door, she would look like a princess, and I’d feel like an ugly duckling.

I might set up the scene like this:

I lost it after beating the bathroom door for days – BAM! BAM! BAM!

“MOM!” I bellowed like a crazed, tortured animal. “I can’t hold it!”

Drizella yanked open the door with such force that I shot past her and slammed into the sink.

“You’re twisted,” she said, glaring at my crumpled form.

“Yeah, well, ouryay airhay ookslay eirdway!” I said in Pig Latin. She’d probably fussed before the mirror this whole time, yet her hair was still a hill of hay.

“MOM!” she tattled, as she caught me in the mouth with hairspray.

“Blecch! Ptooey! Gick!” I reacted loudly, trying to play on Mom’s sympathy.

“Etgay inyay ouryay oomray!” Mom hollered, not fooled about who’d started things. “Ownay!”

My jaw fell so far it popped out of joint. Mom had figured out Pig Latin!

If you’ve ever tried to hide your rudeness and forbidden plans from a parent, you’ll get why my heart exploded. Mom may have understood Izzi’s and my wily conversations!

In this section, I changed the real names in ways that are personal to me. Drizella refers to Cinderella’s mean stepsister. Izzi’s name, which is the same forward and backward, means “naturally upbeat.” Wordplay makes the text lively but also allows me to express and release inner emotions I experienced all those years ago: my close connection to a conspiratorial friend, my jealousy of an uncaring sister, my fear that my strict mother would curtail my freedoms if she heard things I’d said.

I fled – from my room to the roof and down the apple tree. After biking to Izzi’s house, we walked to a nearby bridge as I relayed this shocking news.

“I wonder if I said anything incriminating!” I said.

“Well, water under the bridge, right?” she said while slinging a stone into the water under the bridge.

“Ugh. Now it’s back to the drawing board,” I said, pulling a small drawing board out of my backpack so we could figure out a new secret language. We sat and leaned against the railing while I railed.

Credit: Cleanpng

Finding the words to tell what happened back then and how it affected me feels impossible without using wit and humor. What’s important and healing for me is that this kind of writing infuses my stories with the authentic me, the one who’s still discovering my underlying truths and working through my emotional baggage. Hopefully, it provides some laughs too.

***

The process of “becoming” is one of evolving. I didn’t suddenly love wordplay as that green-bean-hating teenager, or years later – as an adult – pick it back up as a preferred writing technique. Rather, becoming a Wordplay Master was a slow, lifelong process.

My mother told me that when I was a toddler, certain words, phrases, names, and even sentences could make me laugh, clap, and squeal, like the whimsical rhyming pairs in Ape In a Cape by Fritz Eichenberg (e.g., carp with a harp, pig in a wig). Children’s/YA author Iva-Marie Palmer says, “[M]aybe the quickest way to prompt a baby’s belly laugh, a toddler’s infectious giggles, or a kindergartner’s shrieks of delight is by reading aloud a silly picture book.”

Mom’s car after the accident in which we were seriously injured.

Thank goodness that’s the case, because I was in that car accident with my mom. I was four, and for months I was in the hospital in traction. An elderly woman there read me dozens of picture books. When I returned home imprisoned in a body cast, family members read to me. Was laughing at picture book words and images my way of dealing with the hurt, fear, and distress?

By kindergarten, I was a fervent fan of picture books that made me laugh out loud. I found the school primers boring. But luckily, there were authors like Dr. Seuss. Although I didn’t realize he was engaging in wordplay, I loved his names for characters (Yertle the Turtle), things (Sala-ma-goox), and places (Motta-fa-Potta-fa-Pell).

When I was six years old, my teacher sent a progress report to my parents that said, “Gail enjoys reading a great deal. She’s also made great strides in her writing.” That was the year my younger brother died during childbirth. That was the year my mom started sleeping a lot. That was the year the order, “go to your room,” felt like a good thing because I could read, doodle, and create tales in my head to my heart’s content.

In seventh grade, the year I met Izzi, I morphed into a wordplay writer when we bonded over our love of reading and writing. Besides speaking in scrambled languages, we wrote stories and comic strips about our middle grade exploits, and peppered them with as much foolish, secretive, outrageous, corny and/or coded wit as possible. We did this mostly in school, because after school, I had to work with my dad, who was a roofing contractor. The hours were long, the roofs were high, and I felt even more like the tomboy Mom called me.

Izzi and I were just beginning to learn in school about the endless kinds of wordplay. We tried various techniques, but mostly we were just having fun, forgetting our family troubles or working them out in humorous ways through our writing. And if our stories made our friends laugh, well, that was pretty awesome too.

During those junior high years, I was addicted to Roald Dahl, who was a wordplay expert. He invented unique words (biffsquiggled), combined words to create entertaining ones with the same meaning (delumptious), and used spoonerisms – which are words made by swapping the starting sounds of two words – such as catasterous disastrophe. I acutely related to Dahl’s Matilda Wormwood, a spirited and sometimes naughty underdog who serves up justice in Dahl’s word-playing arena.

Photo Credit: freepix.com

With humor and wordplay as my comrades, I wrote and wrote and wrote myself into adulthood, because even when it was difficult, I felt good while doing it.

And I’d learned that it benefits children – my audience. There’s a plethora of research claiming that playfulness – besides being pleasing and gratifying – also teaches and heals. It helps young people understand their world, develop their imagination, and manage stress. The reader’s ability to recognize wordplay tactics depends on the reader’s age, but the light-heartedness of the story will likely come through to all audiences.

As Reading Rockets states in its blog piece, Play With Your Words, “Young children delight in rhymes, hidden letters, and tongue twisters. Older kids love plays on meaning and the silly things that can happen when punctuation is missing.”

***

Fast forward to after my children were born. By the time my youngest was two, we were becoming a broken family, and I was transitioning into single parenthood. One of the boys’ two surviving grandparents died and the other was battling with dementia.

Knowing from my past what helped, I read funny books to my sons constantly. Out loud. With vigor. Using sound effects. “Mr. Brown can MOO MOO! Can you?” We laughed. We rolled. We often got past our doldrums and our sadness and our fears. I was able to see firsthand the important role of wordplay in children’s/YA stories.

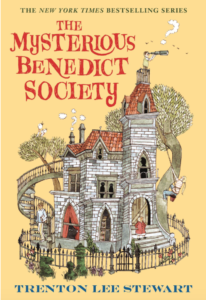

Aspiring to achieve Wordplay Master status, I examined hundreds of texts to determine how, where, and why authors who write for young readers employ this technique. If you want to see wordplay at its finest, here are a few Middle Grade/YA books that are swarming with madcap wordplay: The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, in which idioms are taken literally (people actually make mountains out of molehills); The Wee Free Men by Terry Pratchett, where you’ll find plays on names (the witch’s name, Miss Tick, sounds like “mystic”); and The Mysterious Benedict Society by Trenton Lee Stewart, who uses acronyms to abbreviate but also to reveal more (the M.A.S.T.E.R. – Minister and Secretary of all The Earth’s Regions – truly is an evil “master”).

Learning from the best, I wove similar wordplay strategies into my first middle-grade fantasy novel. You can unscramble the malicious Sed Karnes’ name to spell “darkness,” and a R.E.B. isn’t just an insurgent, but also a Repressed Energy Being.

I’ve gotten pretty good at playing with words, but I’m still “becoming” an expert.

***

Everyone, whether young or adult, manages stress and life’s difficulties differently. During my lifetime, reading and writing humor brought me joy and tempered my struggles. In the process, I became a children’s author who uses wordplay to make kids laugh.

As I continue to discern why and how I write, wordplay will remain my companion. In the words of poet Heather McHugh, “No word-fun should be left undone.”

After my outing with Izzi on the bridge, I snuck back into my house and couldn’t resist interrogating Mom about cracking Pig Latin.

“How’d you figure it out?” I asked. This information would be useful for outwitting her in the future.

“A little birdie told me,” she said, patting the parakeet on her shoulder that was cheep, chirp, tweeting into her ear.

“Are you sure it wasn’t a fly on the wall?” I asked. Two could play at this game. Grinning widely, I swatted at the fly crawling toward the ceiling.

Photo Credit: Madison O’Friel/Unsplash

Gail Vannelli retired from a career as an attorney in 2016 and actively pursued fiction writing, mostly in the MG and YA genres. She has her MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts, and her Post-MFA Certificate in the Teaching of Creative Writing from Antioch University Los Angeles. She is an industry news reporter and writer for Cynsations and has worked at Lunch Ticket as a lead editor, assistant editor, interviewer, and blogger.