Being Biracial: The Identity Crisis of Both and Neither

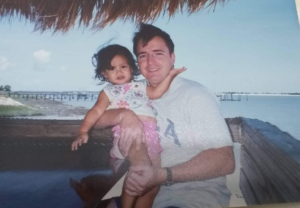

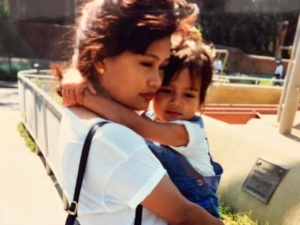

I have never felt like I belonged to a group of people. As a kid, I spent half my time with the white kids and the other half with the Asian kids. And through it all, I never felt like I truly fit. In middle school, I gravitated toward the Hispanic and Black kids because being half-Filipino felt closer to their cultures. I spent most of my childhood on American military bases overseas. My dad, born in Florida, served in the U.S. Air Force for 22 years, and my mom was born and raised in the Philippines. She lived in Pampanga, where the Clark Air Base was, until she met and married my father, who was deployed there.

I was disconnected from Filipino culture in many ways. I knew how to say thank you, Salamat, and how are you, Kumusta? But beyond loving the dishes my mom made on occasion, adobo, sinigang, I was an Asian-American girl. English was my only language, and Western culture was all I knew. Until my parents divorced, and my mom moved me back with her to the Philippines.

I was disconnected from Filipino culture in many ways. I knew how to say thank you, Salamat, and how are you, Kumusta? But beyond loving the dishes my mom made on occasion, adobo, sinigang, I was an Asian-American girl. English was my only language, and Western culture was all I knew. Until my parents divorced, and my mom moved me back with her to the Philippines.

I was thirteen, and until then, I’d grown up around different races and just thought, Yeah we’re all different but we get along. The first time I knew something was off was when I tried to ask a girl in school where the bathroom was and she repeated the word “bathroom” back to me giggling, as if how I said it was wrong, exaggerating the “a” and dragging out the “oo.” She was mimicking, or should I say, mocking my American accent.

My mom enrolled me in an English-speaking private school, but that didn’t stop students from saying things or sharing secrets in Tagalog behind my back or calling me by my last name because it sounded foreign to them. I learned Tagalog in less than six months, but I could never win. If I mispronounced a word, I was laughed at and told to “Just speak English.” But if I spoke English too much, I’d get the look of “Does she think she’s better than us?”

I was branded the “white girl” for years, well into college when my caucasian features started becoming more prominent–my nose and jaw were thinner and higher, my eyes wider, my skin, freckled due to the omnipresent sun. A complete paradox, I was excluded for not being a full Filipino but also idolized for it. I’ll admit, sometimes I liked it. In a world full of browner people, I was the “ideal” color. Because of Western influence and 400 years of Spanish colonization, Filipino society has an obsession with being fair-skinned. All the billboards and the products in the stores tell you one thing: You need to be lighter. I was asked to model several times because of my “clean” skin, and when I watched the local TV shows, there were actually girls who looked like me. Fairer and taller due to being mixed with some kind of caucasian.

A decade into living in the Philippines, I still didn’t feel like a Filipino, and I longed to move to the States where maybe I’d fit in better. I made a promise to myself that on my 25th birthday, I would take a trip to New York, my dream city. All the movies I loved were based there: The Devil Wears Prada, How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days, 13 Going on 30, so I saved up and flew there on my own. The minute I landed, I felt different, like a new person, like someone who could recreate herself and reintroduce herself to the world. It was my first time being back in a place where I thought I could belong. Despite my hopes, racial identity proved to be an even bigger monster in the States. Anytime someone asked me where I was from, to which I’d reply Manila or the Philippines, they would be shocked. They’d say,“Wow, you speak English so well.” Or, “Oh I knew you were some kind of Asian! You look so…exotic!” It’s crazy how people actually think appraising someone like an animal in a zoo is a compliment.

One evening, I was at a bar talking to a man who was also a writer. We were drinking and laughing, having a good time, until he assumed I’d lived in New York all my life. I almost lied and said yes, but instead I told him I was just visiting from Manila. He didn’t know where that was, so I said “the Philippines.” He mouthed an “Oh” and then said he was going to get a drink and never came back. He could have gotten distracted and started talking to another group. Or maybe, he didn’t want to talk to someone from a “lesser” country or race.

I had one too many encounters on my trip to New York (and then in Australia where I moved a year after), people asking me where I was from, getting shocked, then asking me even more questions. I know they meant no harm, but they had me wondering how uncivilized they believed the Philippines was. I was once asked by an older man if Filipinos still lived in huts. When I would name a common food chain like KFC or Burger King, or a retail store like Zara or H&M, someone would ask, “They have those there?” But the most aggravating statement of all was, “I didn’t know the Philippines was in Asia.” Several times I was tempted to ask, “Well where did you think it was?” and slap them with a geography lesson. Even more awkward were those occasions people tried to guess my ethnicity. It was as if they were insinuating that, even though I was half-caucasian, I was not white enough to escape their scrutiny or insatiable curiosity.

I left New York very confused by how I was treated. It was in direct opposition to the treatment I received in the Philippines. I felt doubly shamed – first by the derogatory way the other side of the world viewed Filipinos. Secondly because I was Filipino. All of a sudden, just to alleviate the stress of explaining myself, I wanted to be more white.. But this also made me feel terrible, like I was rejecting a huge part of me, and ignoring what Filipinos have had to face for centuries. I read stories of Filipinos migrating to the States and the UK only to get jobs in the service industry because their degrees weren’t acknowledged. Women, girls practically, being trafficked into prostitution, or sold off to be married to older men. That was the collective view of Filipinos: They exist to serve, to pleasure, to be under. They are inferior.

Credit: Getty Images

I moved to L.A. six months before the pandemic hit. I spent my first year in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death and in the middle of BLM protests. I watched, horrified, at the things being done to Black people. In all honesty, I’d never truly considered their experience. I was ignorant. I tried to educate myself on systemic racism and am still learning how the sins of this country’s past are ever affecting Black communities.

I went even further to learn what Hispanics and Muslims suffer here by reading news stories and watching documentaries, as well as through social media where a lot of people have been brave enough to share their experiences. And yes, I learned what Asians suffer here. Today, we live in an overwhelming crisis of anti-Asian hate crimes occurring all over the country. From elderlies being beaten to six Asian women being shot dead in Atlanta last month. I am horrified by these violent acts of racism toward the Asian-American community, and I’m upset that, unlike #BlackLivesMatter, #StopAsianHate hasn’t motivated social action in the same way. There has been rampant racism towards Asians in America for over a century, and now that hate has been amplified because of a virus that came from “that side of the world.”

Credit: Nikkei Asia

I’ve silenced myself many times, afraid to be perceived as inserting myself into the narrative when I have the privilege of being white-passing. I have not suffered the same kind of racism, discrimination, or hate as other Asians or communities of color. I was not my mom thirty years ago, being told to go back to her country by a man wearing an American flag hat – a flag that is supposed to mean freedom, tolerance, acceptance.

So what right do I have?

I have been on a seesaw my entire life, wishing I was more of one color than the other. It’s convenient for me to insert myself into the reality that Asians are mistreated, assaulted, and discriminated against because I’m Filipino. It’s also convenient for me to avoid being mistreated, assaulted, and discriminated against because I’m white. Even when I want to say we, Filipinos, endure racism on a daily basis, I stop myself. Again, what right do I have? What actual shared experience can I offer? Have I been denied service or overlooked for a job? Do I really face the same fears of being slit across the face in a subway train, shouted “Virus!” at, or other dehumanizing racial slurs? Being half-Filipino hasn’t stopped me from opportunities and hasn’t victimized me in any way. But, simultaneously, has being Filipino caused me to feel unaccepted or unwanted in some places? Has it made others question my credibility and authenticity? Has it allowed for people to say things they wouldn’t dare say to a white woman like, “She must be a good wife because she cooks, cleans, and doesn’t argue with her husband”?

The answer to every question is yes. I have dealt with microaggressions and racial stereotyping to some degree, enough to make me question my value, my place, and my future in this country. And yes, someone has actually implied that I must be a good wife because I’m Filipino and that’s synonymous with being submissive. When I talk to people like me who encounter or deal with the same issues I do, I realize something: Our experiences are a set of their own. Our experiences are very much real and very much valid. Our shared confusion about our racial identity and how it hinders us from truly taking pride in one race when the other tends to cancel it out is a fight in itself.

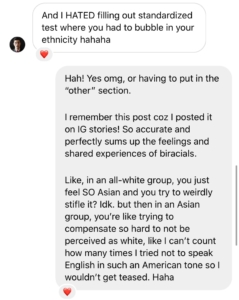

The struggles and tensions of being biracial is a narrative many have yet to really understand. The struggle of being biracial is less about a mix of two cultures and more about having your foot in the door of both and not being able to enter either fully. It is the feeling of being both and neither at the same time. It is the seemingly trivial act of having to fill out a standardized form and marking “other” but knowing that this word shapes your entire existence: You are an “other” in this country or group of people just as much as you are an “other” in that country or group of people.

Those of us who are biracial, and especially those who are half-white, may never know where we truly fit. For some of us, it is a constant adjustment. In an all-white group, we try very hard to stifle our Asian-ness and even laugh along with racist Asian jokes (sadly). In an Asian group, we compensate just as hard to not be perceived as white, whether by trying to water down our thick American accents or not speaking English at all. For me, code-switching like this elicits a two-sided guilt. Downplaying my Filipino side to feel accepted and downplaying my white side to be considered the minority.

But maybe this struggle is actually some kind of ironic gift. We work harder to empathize, and we work harder to check ourselves so we aren’t lording one race over the other or using one to our advantage.

We also know that any racism is simply racism, and if we have felt it or experienced it, it is our right to speak up and speak out, for ourselves and on behalf of others. The Filipino experience and the Asian experience are multifaceted, and despite the ways my experience aligns and doesn’t with the narratives therein, these ARE my people. I grieve with them, I feel their pain.

But whiteness still feels like a cross to bear. I don’t feel as if I can confidently stand in arms with my fellow Asians when half of me feels like the problem in the first place: The privilege that comes with being white pains me, the fact that it “exempts” me.

As a biracial person, I carry the weight of a dichotomy, two histories so intertwined yet so opposed to one another, two cultural extremes, two colors, two races. But I am one person living and coexisting in a world with so many different people, in a country where the minorities will soon become the majority; this generation already has more mixed people than ever before. We will become the new normal. And maybe that’s a good thing, maybe in our shared experience of inheriting two races, we bridge the gap between worlds. We are the marriage of multiple cultures, celebrating them equally. I perhaps will never feel like I belong to a single group of people, but that gives me more motivation to strive for balance and adaption, to hold myself accountable to both, and to not allow myself to lean to whichever side is more comfortable or convenient. I am also realizing that my racial identity shouldn’t control how I view myself, my worth, or what I stand and fight for. I am biracial, it comes with both advantages and disadvantages (as every identity does), but it’s what makes me, me.

Julz Savard Hall is a Filipino-American writer from Los Angeles, CA. She has a BFA in Creative Writing from Ateneo de Manila University and is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University Los Angeles. She works for a nonprofit as a Communications and PR Specialist while completing her first YA manuscript.