Beyond the Pale

I’ve worn different races as if they were shades of pantyhose. Many times, they felt just as constricting. They were not always adopted willingly, but sometimes forced on me. I am mixed; my father is white and my mother is an immigrant from El Salvador. But like all children, I started out raceless, like a page in a coloring book not yet crayoned in. As kids, we marauded through the parks and playgrounds of my mid-western town without ever thinking about the different hues of our skin. For all I knew we looked like the gang of Muppets I saw on TV. Nor did we ever think about whose family had money or which kids wore the nicest clothes. All of our thrift-store clothing was tattered from raucous games that carried us up and down slides and flying from the swings. We could have never guessed that our neighborhood was considered lower middle class because we all felt rich when we traded ten-cent packs of Now and Later and snap-its.

Now, for the first time since childhood, I find myself once again without a race to claim. I wish I could say I have returned to that place of childish freedom where race had no meaning, but I’ve traveled so far from that, I have come full circle. After three years of living abroad, I wish I could say that upon returning to the United States I now feel like I am among my people, or that I belong. But the truth is I feel even more alone.

* * *

Shortly after I returned to the U.S., I moved to New Orleans. I arrived at Louis Armstrong Airport late at night with only a suitcase and a reservation in a dorm at a hostel. I would be starting a writing program the next day and in the next few weeks I would search for a place to live.

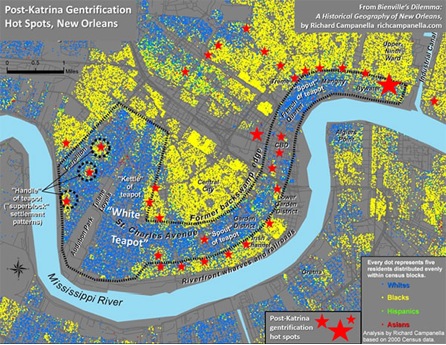

The hostel was located in the Lower Garden District, which I discovered was a curious mix of southern-style mansions, corner stores attracting men with paper bags to their lips, and posh restaurants, which college students crowded into at night. I was confused by the dynamic until a few days later, when I studied a map from Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans. I learned about the historical settlement pattern of whites that formed a tea pot shape within the u-shaped dip of the Mississippi River. This “white tea pot” was akin to Seurat’s pointillism. Tiny dots, each representing five people, amalgamated into a blue tea pot amidst a sea of yellow. The blue dots were the whites, and the yellow were blacks. The overall population of Orleans Parish is 61% black, but the tea pot is a majority white.

I was introduced to my race that first day in third grade when a sneering little boy said, You look dirty.

Whites built their houses and shops within this area because it is the highest ground in a flood-prone city. Its body, or kettle, is a large vicinity encompassing the neighborhoods along the Mississippi River called the Garden District, Uptown, and Carrollton. The spout runs several blocks east through the famed and touristy French Quarter and Marigny. All of the districts that make up the teapot are known for chic studios and resplendent manors, oak trees that sprawl over and shade the sidewalks, and restaurants that serve lavish plates of seafood and steak.

After looking at the map and reading about the history of discrimination in the area, I knew I didn’t belong here.

* * *

When I was seven years old my family relocated to a small rural village. On its surrounding country roads one would find only an occasional stoplight, but at least a few trucks adorned with confederate flags. In southwest Ohio, where many migrants had crossed the bridge north from Kentucky, many seemed oblivious, or at least resistant, to the fact that Ohio was a Union state. In our small town there was a historically strong KKK presence.

On my first day of school in my new town, I was dressed in a silver skirt connected to a satiny cream shirt that had a collar, shiny buttons, and a small reddish-brown stain near my stomach. As I waited in the principal’s office to be shown to my new classroom, I yanked at my tights and fingered the spot, like I sometimes did in church. I wondered whether my older sister had spilled ketchup or salsa, or tried to imagine a stranger who had worn it before her. When the principal escorted me to my new classroom, I entered slowly behind her, stepping into the doorway as I peered across the rows of desks. I saw immediately from the blue-eyed stares of the other students that I looked all wrong.

I was introduced to my race that first day in third grade when a sneering little boy said, You look dirty.

As the years went by, books whose stories paralleled mine provided comfort to me: Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry; Coming of Age in Mississippi; and I know why the Caged Bird Sings. I knew what it might be like to be black because I was black in the minds of my Aryan-featured classmates, who often called me ‘nigger’ as well as ‘spic’ as they pushed me into lockers and threatened to lynch me.

At the hostel in New Orleans, I witnessed a fight in the common room one evening. I was furiously clicking through craigslist ads for housing, hidden behind the screen of my laptop in the back of the room. About twenty feet of sea-foam green carpet separated me and two men who were watching TV. One was white, and he wore a black leather vest, chains, and facial piercings. The other man was black, and he sported a t-shirt and the early onset of a full-size gut. At the turn of the hour they began arguing over which program to watch next. Their voices rose all the way up to the high ceilings. The black guy got up from the couch and started to walk away. As he crossed the room, the white one yelled after him, “You’re just a fuckin’ nigger.” I cringed and filled with heat. I imagined I knew what would happen next because I’d been there myself, throwing a beer or a fist into someone’s face. So, I was more than waiting, I was hoping for it. But to my surprise, nothing happened. The words hung in the air unchallenged and the man left. I was flushed and trembling with anger as I packed up my computer and belongings.

The hostel’s position in the teapot was tenuous. It was located on the last street of the lower border of the spout, and if one walked south the Victorian houses became vacant warehouses. On the outside, its hulking brick facade was decorated with white metal latticework and precise landscaping, which matched the character of the surrounding mansions. On the inside, however, the floral upholstery was as faded as the faces of the other guests, most of whom were actually down-on-luck locals or new transplants, and their sagging smiles called for another drink. Black plastic bags and duct tape, which protected the mattresses from bed bugs, rustled me awake at night. My food disappeared from the refrigerator and a weary maid carting an industrial hamper complained that prostitutes gave her too much work. But no one would guess these things about the hostel just by looking at it.

A couple of days later I moved out of the hostel and into a weekly room rental in Mid-City where I continued my search for housing.

I asked anyone I could about the neighborhoods, and the answers often varied according to race. Black residents suggested the 7th Ward or Gentilly, while whites advised I live in the teapot or other predominately white areas, such as Lakeview. One white woman also warned me not to take buses because they weren’t safe. I wondered how she thought I might get around without a car.

People have always made presumptions about my race. In the area where I grew up, other kids would ask me, What are you?

Human, I began to reply.

Then, when I left to attend college in Columbus, I faced an altogether different kind of reaction: surprise.

I just thought you were white.

Interestingly, I don’t recall an African-American or other minority ever saying this to me. They are more likely to ask me my race or later tell me, I knew you were something. Perhaps this is because they know how high the stakes are when it comes to race, whereas obliviousness is yet another form of privilege.

For a large part of my life I was told I was not white—was not allowed to be. I was degraded and humiliated in the name of my otherness, and I would not let whites take this identity away from me as easily as they had branded me with it. I viewed this as just another attack on my self-determination. I almost preferred the more overt tactics of my high school classmates. At least we both knew where we stood in relation to each other.

Too often whites have assumed they are in like company when they have made racist jokes or comments in my presence. One stranger even paid my boyfriend’s and my bill at a Japanese steakhouse after discovering he had offended me. This stranger certainly must have known that payment could not rectify his words, but he could not have known that the deeper injury had been caused by my boyfriend’s silent assent to his bigotry. The betrayals by loved ones—friends whose true feelings came out after a couple beers or family members at Thanksgiving letting a word slip within my earshot—hurt most.

White liberals advised me that the New Marigny was “up and coming.” Later, I learned this neighborhood was just north of the Marigny, on the southern border of the 7th ward, which was predominately poor and black. The area was undergoing gentrification, a loaded word here in post-Katrina New Orleans.

Given my history, it is probably no wonder that I have trouble trusting the intentions of gentrification. Although I would like to believe it rests on ideals of diversity and integration, the reality of displacement inspires bitter thoughts of modern-day colonization.

I avoided this area, with its not so clear-cut lines.

I considered the Tremé as an option, which was about a thirty minute walk south from where I was staying in Mid-City. Of course, I’d heard about the TV series by the same name, but what interested me most was that it was historically a racially mixed neighborhood, an identifier that resonated with me.

As I zigzagged my way down the streets, one house blasted me with its sound and color: bright blue and purple paints and speakers playing brass band music. I stood at the sidewalk, at the helm of a well-manicured lawn where statues of animals and religious figures emerged from the green grass. I read a message posted on the house: a eulogy to the owner’s dead son who was murdered at its steps.

The house was still in Mid-City, but it set a somber tone for the rest of my walk. I breathed the air a little more deeply as I continued on.

I walked through the heart of Tremé, not the edges that met with the French Quarter, which were also being gentrified. As I walked, male teenagers shouted to me from a car tremoring with bass, and a drunken man with a Saints shirt saluted me with his beer in celebration of the day’s game. But for the most part, the neighborhood was almost eerily quiet, with no one but me walking along the edge of the street where there should have been sidewalks. The houses were humble, with dilapidated and vacant buildings scattered between them. Scrawny trees reached no farther than the rooftops. I saw no grocery stores, but several liquor stores. As I returned to Mid-City on a more main thoroughfare, I occasionally encountered small groups of young African-American males leaning against railings and resting on porch steps. They ignored me. But I was still struck by the same feeling as when I lived in Africa and groups of children would yell at me “La Blanche!”

* * *

Never had I felt such shame to be part of a collective whose actions I could not control.

I became white when I moved to Cameroon. In looking at what it means to be white, privilege is one of the primary indicators. Certainly, I recognized this in Cameroon, where I lived for over two years serving as a Peace Corps volunteer. As a result of my skin color I achieved a special VIP status. I could commandeer the front seats of the bus, finagle my way out of cover charges into clubs, and strut through special events of the elite class, where I certainly had never belonged before. Of course, such a celebrity status was not without pitfalls. I was continuously barraged with a variety of requests for not just money, but sometimes the shoes worn on my feet or the purse carried on my shoulder. Vendors attempted to charge me three to four times the actual price of goods—something my fellow volunteer and I called a ‘white man tax’ or sometimes formed into a verb: he tried to ‘white man’ me. If I even attempted to explain to my friends that I was not really white, my tale was met with hearty laughter.

Crazy white girl.

In their eyes I was rich.

I became defensive.

I would scream at taxi drivers who were trying to overcharge me. I blamed the country’s poverty on the people’s political apathy. I ignored how America’s wealth was bought with their poverty. I walked around with a guilt that was intangible but ready to defend itself.

This proved me to be white, as did my struggle to understand my own whiteness.

One night, a group of my fellow ex-pat Americans met in our regional capital, Maroua. We spilled across three outside tables of one of the many bars that lined Rue de Mayo, amidst the crowds of young Cameroonian men standing in social circles along the street or seated nearby. Without street lamps, the night was dark and the thrum of motorcycle taxis, dust, and rhythmic beats filled the desert air. We drank.

Towards the end of the night, a faction of our larger group had become incoherent, stumbling, and sloppy drunk. One guy vomited on the side of the building. A few of the young women went inside the bar to dance provocatively with men. One of them was dressed in a low-cut shirt so that as she began kissing her dance partner, her breast was revealed in its entirety.

Never had I felt such hyper awareness of how others’ acts were also mine. Never had I felt such shame to be part of a collective whose actions I could not control.

In the Tremé I stood face to face with poverty, and just as I had been forced to in Cameroon, I confronted my own privilege. I thought about my friends in Cameroon who would have been grateful for these houses whose walls didn’t collapse with rain and whose faucets gave water. I was ashamed to admit that two years in Africa had not strengthened my tolerance of poverty; it had weakened it.

* * *

One day, while I was viewing an apartment in Mid-City, I noticed a school called Esperanza, meaning ‘Hope’ in Spanish. My heart welled.

For several years, I was Hispanic. In college and the years after, I delved into my mother’s culture. I became President of a Latino co-ed fraternity, and worked in the immigrants’ rights movement after attending law school. This was my time to be fully Latina—to rebirth myself as the strongest version of what whites rejected, pushing myself farther away from them on the racial continuum.

In many ways, this place felt natural. I had grown up to the soundtrack of Jose Vicente’s anguished rancheras and gritas. I had patted masa flour with my hands until the dough almost formed a circle, even though my tortillas were always too thick. And my mother’s accented English and quirky parenting tactics resonated so strongly with George Lopez’s stand-up comedy, my lungs ached from laughter.

Before Katrina, the Hispanic community in New Orleans was small, leaving little impression on the city. Post hurricane, large numbers of Latino laborers migrated into New Orleans to help with its rebuilding efforts. Many have stayed, and estimates show the Hispanic population may more than double in the next five to ten years. Mid-City has seen the largest increase within Orleans Parish, although the suburbs have seen even higher numbers. Still, because it is a rather new immigrant community it has the typical characteristics of such: hidden and closely-knitted.

Each time I speak Spanish or dance salsa, I feel like I am revealed as a fraud. I speak fluently but with an American accent and the grammar of a six year old. My hips go rigid when I try to swing them to the beats of Celia Cruz, even though I can shimmy and pop to Petey Pablo.

However, there is so much more that separates me and a Latino laborer.

I know that being Hispanic is not something I can fully ever own.

* * *

Recently, I traveled through Africa, South East Asia, and Central America. For the latter regions, I was once again raceless. I was simply a foreigner, an American. I was reminded of a statement I’d read written by Albert Murray: “For all their traditional antagonisms and obvious differences, the so-called black and so-called white people of the United States resemble nobody else in the world so much as they resemble each other.”

During my travels, I met three Americans while crossing the border from Zimbabwe to Zambia. We spent Christmas together, sharing a buffet of Greek salad, lasagna, and pumpkin ravioli at a restaurant in Livingston. Before meeting them, I hadn’t seen another American in weeks. The familiarity of their speech and attitudes warmed me; it felt like a homecoming. One woman was bi-racial and the other two travelers where white, but I embraced them all equally as family.

After traveling for nearly a year, the Atlanta airport was my re-entry point into the United States. Here, I saw for the first time how skewed my perception of race had become. I had arrived from Guatemala, where I’d spent the last two months writing essays and refreshing my Spanish. I waited at the luggage carousel and watched as my companions from my plane grabbed cellophane-wrapped suitcases that were nearly the same size as them. But the machine did not feed my bag out. After a while, I scanned the crowd to see who was left from my flight.

Now, most of the bystanders were wearing plaid shorts, sunglasses used as head gear, and brand-name neon tennis shoes. Apparently, another flight had arrived. None of these white people were on my plane, I thought to myself.

That’s when I recognized that the people I was referring to as ‘white’ included African-Americans and excluded only a few of the Latin Americans who were left. I was confused by my own thought process until I realized my racial categorizations were no longer based on race, but perceived wealth.

My baggage never came, and I passed through U.S. customs with nothing to claim.

In some ways, there is freedom in this kind of existence. I can move in and out of races, and I do. Noel Ignatiev coined the term race traitor to describe someone who seeks “to abolish the white race, which means no more and no less than abolishing the privileges of the white skin.” Sometimes, in discussions about social issues, I do not reveal my race because I have learned my opinion carries more weight if I am perceived as white. In accordance with Ignatiev’s ideology, I am not trying “to pass;” I’m practicing racial espionage. Ignatiev believes that abolishing the white race requires “the defection of enough of its members to make it unreliable as a predictor of behavior.” He rests these claims on the principle that “treason to whiteness is loyalty to humanity.”

My loyalties are unbending.

I discovered a compassion in Africa that knows no enemies. There, I learned what it felt like to carry the burden of oppression in a different way. For the first time, I had to take responsibility for the charges I had previously dispatched to others.

I learned that we all have to take responsibility for each other.

The most racially diverse tract in Orleans Parish is a three-block group area within Mid-City. When I stood in front of Esperanza School, I did not know I was standing just a few blocks south from this tract. I watched as a Hispanic woman guided her daughter across the street by the hand. I walked on, and shortly after, an older African-American gentleman asked me for a dollar. I shook my head because I didn’t have cash, but we spoke for some time about where he might stay the night. He was a veteran from North Carolina. As I continued, I passed a smiling white couple who moved over for me on the sidewalk.

In each of them, I saw a part of myself.

A few days later I put down a deposit on an apartment in Mid-City.

I still can’t say I feel I belong here, but I think it is the closest I can come to the feeling of belonging. I doubt I will ever truly belong anywhere. Even though I have found a place to live, my search for a place in New Orleans and America continues.