Bridge to Nowhere

Bridge to Nowhere

I thought a lot about my daughter Reiley during a recent hike with my sons to the Bridge to Nowhere. Constructed in 1936, the 120-foot arch bridge over the San Gabriel River was part of the East Fork Road meant to connect the San Gabriel Valley to Wrightwood. It was washed out by a flood in 1938 and remains stranded in the Sheep Mountain Wilderness. Reiley is a freshman in college in northern California and misses hiking in the mountains nearby our home in Riverside. She would have loved this trail, which winds through riparian woodlands, yucca gardens, and fields of tall grass studded with granite boulders.

Reiley is tall and broad-shouldered with the long, lean muscles common to distance runners. Always strong and fit rather than lanky, when Reiley came home at winter break, she was skinny—at least, a full size smaller than she had been when school started in August—and skittish. “I’ve just been working out a lot,” she said. No doubt. Reiley had competed on her school’s cross-country team in fall. She was also unusually picky about her diet and short-tempered when the family’s schedule or foul weather upset her exercise plans. “Oh no,” I thought. Rapid weight loss, unnecessarily restrictive dieting, and obsessive exercising are signs of anorexia nervosa, a potentially life-threatening disease from which I am still recovering.

For me, recovery consists of conforming to deeply internalized rules that ensure adequate nutrition without risking the slippery slope to obesity that resides just shy of normal weight in the imagination. My mealtime decisions are quick, and I don’t crave rich, decadent, or unhealthy fare. I simply appear to eat like a thin, active woman committed to a healthy lifestyle.

“I’d like the salmon. Can you substitute salad greens for the rice?” I asked when it was my turn to order at a work-related dinner last week. “Yes, of course. What kind of dressing would you like?” the server asked. “Vinaigrette. On the side. Thank you.” Salmon is not my favorite food, nor did I feel like fish. Rather, it satisfied my “protein and veggies” rule for eating out. I also had a glass of red wine and just a bite of chocolate-raspberry cake.

Reiley returned to school in mid-January and began training for the crew season. I hardly recognized her when we met in San Luis Obispo eight weeks later. Reiley’s workout tights hung on her, ruffled just above her hips where she’d tightly knotted the drawstring to keep them from slipping. Her head was perched on a painfully thin neck, dwarfed by the raised collar of her bright pink down jacket, which seemed to be suspended inches beyond the perimeter of her body. She was wearing two additional layers underneath, though at seventy degrees, it was a relatively warm day. I was shocked, scared, and wracked with guilt. Why the hell did I let her go back to school at the end of winter break?

Anorexia, characterized by self-starvation and excessive weight loss, has existed since the 12th century in the guise of ascetics’ refusal to eat and more commonplace instances of “wasting disease.” Reported cases of anorexia have increased steadily since 1930, escalating from the 1970s and ’80s, coincident with both the unprecedented rise in obesity and the emergence of dieting as a cultural practice.

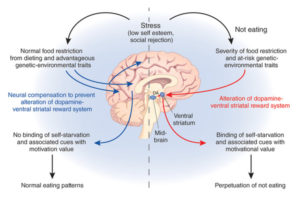

Although researchers and clinicians do not know exactly what causes this complex disorder, there is an emerging consensus that “genes play a major role” (Kaye et al. 2014). According to Cynthia Bulik, a psychologist who specializes in disordered eating, there is no “anorexia gene,” but rather a number of genes that dispose an individual to develop the disease. These genes are likely to include those that govern personality variables, such as anxiety and perfectionism, those for hormonal and metabolic factors, and those for appetite. Addled by underlying neurobiology, an individual suffering from anorexia responds to physical and emotional stress by obsessing over food, exercise, and weight loss.

I was somber, fastidious, and anxious even as a young child. Always a finicky eater, I cut meat and sweets out of my diet in third grade after a stout great-aunt teased me about accepting a second helping of apple crisp. “I used to eat like that when I was girl,” she said. I put my fork down and left the table.

I experienced three bouts of rapid and significant weight loss, accompanied by fanatical exercising, before losing more than thirty pounds during my freshman year in college. I knew Reiley was homesick and overwhelmed by her classes, training, and work. Still, it never occurred to me that she would starve herself. Reiley was an “easy” baby whose first words included “happy.” While Reiley had favorite foods—peaches, macaroni and cheese, and peanut butter—she had always enjoyed a far more varied diet than I did as a young girl, and easily ate enough to fuel her high level of physical activity. Not anymore. Her diet now consists of vegetables, some fruit, lean protein sources, meal bars, and occasional “treats” such as a slice of Costco pizza or half a brownie.

It’s tough to write about anorexia. Self-exposure can be liberating but also frightening. In addition, writing about anorexia outside of a medical context elevates it to a more interesting place than it arguably deserves. It was tedious to subsist on bran cereal, yogurt, and a limited selection of Lean Cuisine options in college, and to make unnecessary late-night trips to the library or a friend’s room just to run back up the eleven flights of stairs to my suite. But such narratives provide valuable tactical information for anorexics who consume memoirs, confessional articles, and posts by other anorexics, as well as novels about people with disordered eating as how-to manuals for starvation. Cautionary tales about the anorexic experience provide crucial details about how to become the best anorexic: the minimum one can eat and survive, how little one can weigh at a given height, how much and what kind of exercise provides the best chance of weight loss with the least physical exertion as a starving body weakens (Thomas et al. 2006).

I intentionally avoid the risk of glamorizing the practice of self-starvation or revealing its secrets by focusing on recovery. The balance required in writing about life as a recovering anorexic mirrors the balance between responding rationally to nutritional information and dissociating from cultural preoccupations. That is, by grounding anorexia in the contemporary discourse of “brain disorders,” I hope to undermine any applause that might be warranted by disciplined eating to the point of starvation. The recovering anorexic’s story of a potentially “bumpy, messy recovery…full of relapse, self-doubt and…weight gain” is significant because it resonates with universal, human stories of redemption.

Eating disorders are not a matter of food, weight or shape. They are about the discomfort of being human and fallible, something I am sure everyone can relate to in one way or another. ~Louise Harvey

Crossing the San Gabriel River

The trail to the Bridge to Nowhere can be strenuous for those unaccustomed to climbing or unprepared for wading. Though it features just 800 feet in altitude gain, it’s over ten-miles round trip and requires rock scrambling and at least four water crossings. It was cool and overcast the day we hiked, and the water so early in spring was frigid. Reiley would have been exhausted and deathly cold.

For anorexics, the path to recovery is arduous. Like the Bridge to Nowhere, anorexia is alluring, deceptively strong, and accompanied by a neurochemical euphoria that is painful to let go. I was unable to order my eating and allow my weight to stabilize until I decided to become a mother just over twenty years ago. I consciously chose to provide my body with the food-fuel necessary to grow my eldest son, Quentin, followed by Reiley and their two younger siblings.

In addition to supporting Reiley’s medical treatment and counseling, I’ve encouraged her to find a compelling reason for recovering that is more immediate than the still-distant ticking of her biological clock. When she does, I’ll be waiting, like a patient and trusted guide, to show her the way.

Notes

Kaye, Walter H., Christina E. Wierenga, Stephanie Knatz, June Liang, Kerri Boutelle, Laura Hill, and Ivan Eisler. 2014. “Temperament-based Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa.” European Eating Disorders Review. Web.

Thomas, Jennifer J., Abagail M. Judge, Kelly D. Bromwell, and Lenny R. Vartanian. 2006. “Evaluating the Effects of Eating Disorder Memoirs on Readers’ Eating Attitudes and Behaviors.” International Journal of Eating Disorders 39: 418-425. Web.

Juliann Allison is a feminist scholar, environmentalist, homeschool advocate, yogini, runner, rockclimber, mate, and mother of four with a passion for the outdoors. She is Associate Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies and Public Policy at UC Riverside, and an MFA student at Antioch University Los Angeles.