Catechism, Truth, and Creative Writing

I learned that truth may not depend on facts in a classroom at the St. Irenaeus Parish School. As a high school junior, I was among the church’s youngest Catechumens, or unbaptized probationers preparing for the Sacraments of Initiation into the Catholic Church: Baptism, Confirmation, and Eucharist. Although my siblings and I attended mass regularly with our “Cradle Catholic” father, our mother, a nondenominational Christian, refused to support baptism until we were old enough to make a fully-informed decision.

I was a committed student of the faith, yet openly skeptical. During a lesson about the role of scripture versus tradition, in reference to the Church’s mostly unwritten teachings, I asked Father Rod if Catholics regarded everything in the Bible to be true. “Do Catholics believe the earth was actually created in six days? That a talking snake in a garden paradise convinced Eve to eat an apple?”

He said, “Yes. The Bible is full of truths, but not always facts.” He explained that the creation stories in Genesis are symbolic. As for the fruit Eve plucked from the tree of knowledge, ate, and shared with Adam, he said, “It could have been a fig, an olive, a grape … it doesn’t matter.”

Catholics believe that Adam and Eve lived in a verdant garden and were tempted to eat a forbidden fruit, but the lessons associated with their transgression are far more significant than the specific characters, setting, and action in Genesis. Adam failed to protect the garden and his wife, and the couple was consequently banished from paradise. Lesson: There are consequences for our actions. More importantly, Adam failed to demonstrate complete obedience, severing humanity’s foundational connection to God. Lesson: Divine covenant requires self-sacrifice.

Biblical scholarship suggests that Catholics’ approach to Genesis represents a midpoint among contemporary interpretations. At one end of the spectrum, Biblical literalists regard the scripture as history. Adam and Eve, the first humans, really lived in a garden watered by a river flowing from Eden, where they encountered a talking serpent that persuaded them to defy God and eat fruit from the tree of knowledge, a sin that carried harsh punishment, including: pain in childbirth, physical labor, and death. Readers at the other end of the spectrum consider Genesis to be a religious myth—an entirely fictional tale inspired by human desire to know and understand our origins. God created an orderly cosmos from chaos—filling the sky with stars and the earth with vegetation and every kind of animal—and Adam and Eve in his image, who were charged to populate the earth and cultivate and care for Eden and warned that the penalty for eating fruit from the tree of knowledge was death.

Like the good priest said, “Many truths.”

The particulars of our own comparatively more mundane stories likewise hold many truths, often because they originate in memory. We may very well be what we remember (Wilson 2003). According to University of California neurobiologist James McGaugh, memories are “reconstructions,” not fictions. When people “recall … [it] means they’re telling a story about themselves and they’re integrating things they really do remember in detail, with things that are generally true.” Lidia Yuknavitch, author of the “anti-memoir,” A Chronology of Water, would concur. Events occur in identifiable places and at precise times and dates, but they do so “with composition, point of view, blind spots, and tricks of the eye.”

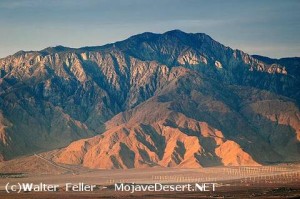

My memories of moving from Southern California to Upstate New York, for instance, are dominated by my body’s physiological response to extreme geographical change. I grieved the loss of high, rocky mountain peaks, hot, dry southwestern deserts, and distant horizons. The cool, wet gloom that shrouded the gray cliffs at the Pennsylvania-New York border chilled me. I felt trapped by the rolling hills that blocked my view. Yet transforming this personal, embodied memory into a compelling narrative would require the basic research on which scholars and writers rely to ground truth in evidence and would thereby increase knowledge and understanding. So, in addition to reading journal entries and looking at photos of my move east, I examined maps, temperature records, and tree and plant keys to select the specific details necessary to ground the contrast between the warm familiarity of my life at home in Southern California and the immediate cold and discomfort of my new environs in Upstate New York.

I left Palm Springs, California early in the morning on a hot August day—nearly ninety degrees; temperatures would reach 115 later that afternoon. I was comfortable in cut-off denim shorts, a sports bra, and Birkenstocks. I climbed into my bottle green Ford Ranger pickup, praying that the truck’s 2-70 air conditioning system—for two windows down at seventy miles per hour—would make the ten-hour drive through the desert to Albuquerque, New Mexico bearable. I started the engine and leaned forward over the wheel with my elbows up to facilitate cooling. I watched the steep, rocky face of Mt. San Jacinto slip away in my rear view mirror as I drove east on the I-10 …

I left Palm Springs, California early in the morning on a hot August day—nearly ninety degrees; temperatures would reach 115 later that afternoon. I was comfortable in cut-off denim shorts, a sports bra, and Birkenstocks. I climbed into my bottle green Ford Ranger pickup, praying that the truck’s 2-70 air conditioning system—for two windows down at seventy miles per hour—would make the ten-hour drive through the desert to Albuquerque, New Mexico bearable. I started the engine and leaned forward over the wheel with my elbows up to facilitate cooling. I watched the steep, rocky face of Mt. San Jacinto slip away in my rear view mirror as I drove east on the I-10 …

It was a cool sixty degrees, cloudy and wet, when I arrived in Binghamton, New York—seventy miles southeast of Syracuse—four days later. My new home faced a hill blanketed by hardy birch; slender, white branches bedecked with still-green leaves rose above the rooftops. I pulled a worn UC Davis sweatshirt over my head as I climbed out of the truck, pushed my fists through each sleeve in turn, and examined my chilled finger-tips for the blue tinge that signals a Raynaud’s attack. Though my hands were already uncomfortably cold due to temperature-induced vasospasms, my fingers remained a healthy pink. I shoved my hands into my armpits to warm them.

It was a cool sixty degrees, cloudy and wet, when I arrived in Binghamton, New York—seventy miles southeast of Syracuse—four days later. My new home faced a hill blanketed by hardy birch; slender, white branches bedecked with still-green leaves rose above the rooftops. I pulled a worn UC Davis sweatshirt over my head as I climbed out of the truck, pushed my fists through each sleeve in turn, and examined my chilled finger-tips for the blue tinge that signals a Raynaud’s attack. Though my hands were already uncomfortably cold due to temperature-induced vasospasms, my fingers remained a healthy pink. I shoved my hands into my armpits to warm them.

More generally, the search for truth often blurs the line between research and creative practices. Creative writing can serve as an artistic means of generating the information typically used to substantiate knowledge claims and increase understanding. Poets, fiction, and creative nonfiction writers, playwrights, and screenwriters use imagery, narrative, and drama to impart meaning about events and concepts. Facts in the form of vivid, sensory, and telling details both establish the narrator’s reliability and help to engender a continuous experience for the reader or viewer. English composition expert Jason Wirtz argues that basic research is so essential to creative activity that writers need to research a topic until they can “embed the research seamlessly into a … story” (Wirtz 2006).

Donna Lee Brien’s biography of Mary Dean, The Case of Mary Dean: Sex, Poisoning, and Gender Relations in Australia, manages to do just that (Brien 2004). Mary Dean was allegedly murdered by her husband on their first wedding anniversary in 1895. Brien’s strategy for investigating Mary Dean’s life and understanding the legal rules and cultural context that enabled her husband to walk free despite the death sentence (Regina v. George Dean, 1895) included close and critical reading; imaginative, speculative, and reflective thinking; experimental and exploratory writing; rewriting and editing; and public circulation and peer review. According to Brien, this work resembled a “state of generative cross-fertilisation” that made it impossible to know if the completed biography was a work of history or creative writing (Brien 2006). Indeed, Brien’s mastery of the Deans’ life story, of the law report “Regina v. George Dean, 1895,” and of gender relations in 19th-century Australia allows the reader to relax and indulge in the narrative.

Donna Lee Brien’s biography of Mary Dean, The Case of Mary Dean: Sex, Poisoning, and Gender Relations in Australia, manages to do just that (Brien 2004). Mary Dean was allegedly murdered by her husband on their first wedding anniversary in 1895. Brien’s strategy for investigating Mary Dean’s life and understanding the legal rules and cultural context that enabled her husband to walk free despite the death sentence (Regina v. George Dean, 1895) included close and critical reading; imaginative, speculative, and reflective thinking; experimental and exploratory writing; rewriting and editing; and public circulation and peer review. According to Brien, this work resembled a “state of generative cross-fertilisation” that made it impossible to know if the completed biography was a work of history or creative writing (Brien 2006). Indeed, Brien’s mastery of the Deans’ life story, of the law report “Regina v. George Dean, 1895,” and of gender relations in 19th-century Australia allows the reader to relax and indulge in the narrative.

So what about Eden, the fruit, and the expulsion of Adam and Eve? Most scholars agree that Genesis was written or compiled during Moses’s life, sometime during the middle Bronze Age (1600-1200 BCE), thousands of years after Adam and Eve were banished from Eden. Given the fallibility of normal memory, the narrative of the Fall understandably contains few specific details, yet sufficient geographic and botanical information to provide a credible context—a warm Middle Eastern climate, a garden of fruit trees (fig, olive, and grape “vine” are native), and a river that divides into “streams” called the Tigris and Euphrates—for a wonderful story that contains many truths.

References

Wilson, Anne E. and Michael Ross. 2003. “The Identity Function of Autobiographical Memory: Time Is on Our Side.” Memory 11, 2:137-139.

Wirtz, Jason. 2006. “Creating Possibilities: Embedding Research into Creative Writing.” 95, 4: 23-27.

Brien, Donna Lee. 2004. The Case of Mary Dean: Sex, Poisoning and Gender Relations in Australia. Queensland University of Technology.

Brien, Donna Lee. 2006. “Creative Practice as Research: A Creative Writing Case Study.” Media International Australia 118, 1: 53-39.

Juliann Allison is a feminist scholar, environmentalist, homeschool advocate, yogini, runner, rockclimber, mate, and mother of four with a passion for the outdoors. She is Associate Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies and Public Policy at UC Riverside, and an MFA student at Antioch University Los Angeles.