Center of the Living Room

My father is a simple man in old age. He lives on the outskirts of Las Vegas now, in a rinky-dink apartment complex. The television blasts CNN at an alarming volume for such close quarters, but he’s outside, minding his business and squatting on the patio with a cigarette between his fingers. In between puffs, he pokes at his quaint, urban garden, a sign of his domesticated life as a retiree. He always wanted someplace warmer than the chilly, wet climate in Seattle, better for tired bones. In his heyday, he was a bell bottom-wearing playboy with dark features and a baritone voice. I always thought he looked like a Filipino Harrison Ford, but he is 73 years old now, his swagger tempered and grey.

My step-mother is inside, always the first to greet me whenever I visit with my children. She keeps a tidy home for my father in their tiny two-bedroom apartment. They returned to America from the Philippines with only a few belongings to send my little brother to college. Now, it’s neatly cluttered with nautical trinkets and various furnishings they’ve collected over the years. Amidst the sea blues, anchors and seashells is a massive subwoofer, now a makeshift side table. The coffee table is slightly askew from the living room futon to make room for my father’s prized possession, an 88-key Yamaha digital piano. He plays it on the futon whenever I visit, but not for entertainment. He plays it because it’s part of his routine, and the sound of him playing is so normal that I don’t recognize he’s playing unless I bring someone over that appreciates his talent.

My step-mother is inside, always the first to greet me whenever I visit with my children. She keeps a tidy home for my father in their tiny two-bedroom apartment. They returned to America from the Philippines with only a few belongings to send my little brother to college. Now, it’s neatly cluttered with nautical trinkets and various furnishings they’ve collected over the years. Amidst the sea blues, anchors and seashells is a massive subwoofer, now a makeshift side table. The coffee table is slightly askew from the living room futon to make room for my father’s prized possession, an 88-key Yamaha digital piano. He plays it on the futon whenever I visit, but not for entertainment. He plays it because it’s part of his routine, and the sound of him playing is so normal that I don’t recognize he’s playing unless I bring someone over that appreciates his talent.

Aside from his “real job” at Boeing, my first memories were running around bars or venues while he danced his fingers along the keyboard. My siblings and I grew up to synthesized disco beats and strobe lights. Our family lived and breathed music: Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, A Taste of Honey, Mouth to Mouth, and every cover song from the 60s and 70s.

As a teenager, I would find him downstairs in the dimly lit garage studio, sitting down next to a lamp, riffing off a song, enveloped in a cloud of nicotine. We didn’t talk to each other most of the time because I didn’t know what to say to my reserved father. Connecting with him was tough when my parents divorced, and I grew more distant during adolescent growing pains. The only time I had a conversation about his music was when I was sixteen after I handed him a sheet of music and asked him to play. He handed it right back to me.

“No,” he laughed, “I can’t read music.” So, he asked if he could listen to the song, some millennial pop ballad, and he played it, improvising with his signature keyboard sound along the way. Anyway, the studio wasn’t a place for bonding. The music slowed everything down. I drifted away in his melodies, further away from anyone, but close to his sound.

The smoky garage studio burnt down years ago in Seattle. (A case of a cigarette thrown in a receptacle. Go figure.) His studio has now been relegated to the center of the living room where he sits down to play a song. Except I don’t drift away this time. This time, I want to know why he plays every day and will for the rest of his life. I do because I’m in my MFA program, and I’m hungry for art and music. I wonder about my creative process, and if it was born out of my upbringing. Now I wonder if it was born out of his. Maybe his hunger is hereditary?

When I sit down to ask him questions, he lights up and tells me stories I’ve never heard and can’t quite picture. My father was the oldest brother of five siblings and cared for the family as the “man of the house” when their father, my grandfather, left our grandmother, the family matriarch. Maybe this is how he obtained his survivor sensibilities, qualities I mistook to be too blunt and hurtful.

My grandmother gifted his first guitar at fifteen and he played every morning after studying others play at clubs. He chaperoned my then teenage aunt when she worked as a restaurant crooner, realizing music was a passion during this time. My father was so good, in fact, that one of the restaurant band members asked him to form a band and tour Japan. He believed he would only be away from his responsibilities at home for six months, but soon he was a college drop-out, leaving his studies in Business Accounting.

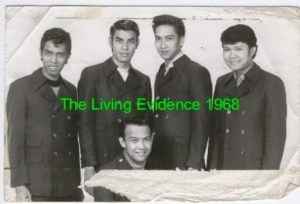

I balked at the earlier prospect—my father bookkeeping in a dimly lit garage. It didn’t equate. But he didn’t choose that path. He stayed in Japan for six years and learned how to play the piano in one month after breaking his finger in karate. My late grandmother proudly showed me a black-and-white photograph of my dad with his band, dressed like an Asian Beatle.

I balked at the earlier prospect—my father bookkeeping in a dimly lit garage. It didn’t equate. But he didn’t choose that path. He stayed in Japan for six years and learned how to play the piano in one month after breaking his finger in karate. My late grandmother proudly showed me a black-and-white photograph of my dad with his band, dressed like an Asian Beatle.

The Japan tour lasted through the 70s near the end of the disco era. My father would have traveled to Singapore had my grandmother not petitioned for him to immigrate to Seattle, Washington, where he met my mother. She reluctantly supported his musician lifestyle for the better part of their marriage, waiting up at night or on the sidelines while my father stayed out for gigs. I watched as his musical endeavors tore at his relationships or mended them, depending on which story I heard. Either way, my father’s keyboard was always the center of his universe and now it was literally center of his living room.

My step-mother tells me he plays the piano every morning, as soon as he wakes up. My father, the simple man, but gosh—did he have glorious adventures. Some might call it foolish or risky the number of times he put music first, but he played because he couldn’t keep his hands off of it. The hunger was always there as soon as he found music in his hands.

When I asked him if he ever sought a record deal, he replied, “No.” He had his heyday, and now he spends days drifting off in chords. “I play to get away from negative thoughts,” he says.

That’s when I realize our creative lives are similar. I didn’t quite inherit the music family trait. I can’t even sing karaoke. No, my fingers drift over a different type of keyboard, the kind that allows me to write about my father and reminisce about disco balls and bell bottoms. I found the hunger in different ways, but there’s the same impulse, the same desire to channel a baritone voice chalked up in smoke, a riff, a melody, then poetry. And maybe I won’t get to live the rock star life in Japan, but I have my center of the living room in me and at my fingertips. I return to it day after day and make it sing, baby.

Cristina Van Orden lives in South Los Angeles with her family and Chorkie. She is currently an MFA Candidate at Antioch University, Los Angeles and Poetry Editor for Lunch Ticket. Her work can be seen or is forthcoming in Chaleur Magazine, Gordon Square Review, HOOT Review, and Silverneedle Press.

Cristina Van Orden lives in South Los Angeles with her family and Chorkie. She is currently an MFA Candidate at Antioch University, Los Angeles and Poetry Editor for Lunch Ticket. Her work can be seen or is forthcoming in Chaleur Magazine, Gordon Square Review, HOOT Review, and Silverneedle Press.