Dal Saves My Soul

“I made dal last night” might be the most unremarkable thing anyone can say because probably so did half a billion people in India alone. I made dal last night in Los Angeles because it rained as much in a day as the whole of last year, and I wanted more than comfort food. I wanted the essence of the cuisine of my country of birth, the first food of all foods, ground zero, the basic building block, the iconic yellow Lego brick. I wanted to eat the thing that reminds me of when eating started, of the foundation on which culinary castles are built that would collapse without the base of it all, the orange that turns into a fluffy yellow, thick, creamy, salty, steamy, garlicky, with a bit of bite on a warm bed of rice: dal, dhal, or even doll as my grandmother, dainty and Indo-European in her sensibilities, called it.

“I made dal last night” might be the most unremarkable thing anyone can say because probably so did half a billion people in India alone. I made dal last night in Los Angeles because it rained as much in a day as the whole of last year, and I wanted more than comfort food. I wanted the essence of the cuisine of my country of birth, the first food of all foods, ground zero, the basic building block, the iconic yellow Lego brick. I wanted to eat the thing that reminds me of when eating started, of the foundation on which culinary castles are built that would collapse without the base of it all, the orange that turns into a fluffy yellow, thick, creamy, salty, steamy, garlicky, with a bit of bite on a warm bed of rice: dal, dhal, or even doll as my grandmother, dainty and Indo-European in her sensibilities, called it.

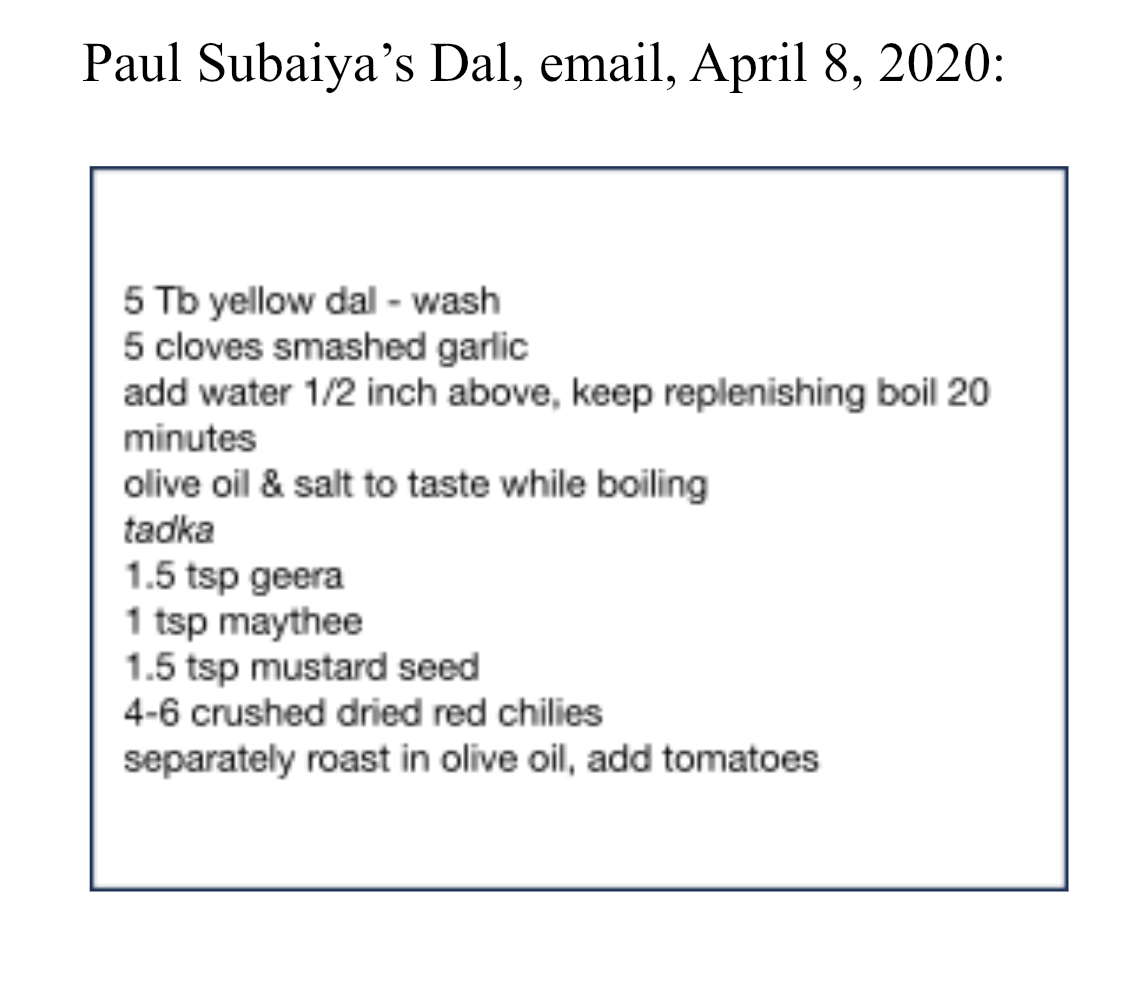

I figured I’d make my dad’s dal again, which, in the way traditions are handed down in my family—on text threads and hastily recorded voice memos, I’d saved as a screenshot of an email sometime in the early days of the pandemic. My father was born in 1940 in Uttar Pradesh to a Bengali mother and a father from Andhra. His dal is actually his mother’s dal. He learned the recipe from watching her as a little boy. “I just followed her around all the time,” he explains. Dal wasn’t just a regular part of their diet, it was served at every meal. His recipe is not exactly hers. She would have used green chilies instead of his dried red chilies, which he and I both agree—so much easier, always around in the kitchen. She also alternated between putting fresh cilantro or curry leaves in the dish. His recipe mentions neither. To me, his version, inspired by hers, is just perfect because it’s simple, restrained, classic.

Given how basic a food it is, dal can be made in a surprising number of ways. First there’s the question of the lentil or split pea itself: urad, masoor, toor, moong, and the harder chana dal. Then the method: to soak or not to soak. To boil or to pressure cook. Seasoning decisions start with what goes into the tadka. Tadka are a collection of ingredients in micro quantities but with an intense flavor that sizzle and sputter in oil for the briefest minute before getting added to the larger dish. Your tadka and my tadka are unlikely to be the same. Methi (fenugreek), mustard seeds, geera (cumin), maybe even a sprinkle of raw urad dal lentils go into my family’s recipe; whatever it is always feels like the stuff of potions that a wizard might pull out of a weathered pouch and not share the names of. Then the rest of the spices, which could include cayenne, green chilies, coriander, turmeric, or not. The question of garlic or no garlic might as well be like the difference between Catholicism and the early Reformation; from far away it’s all Christianity, but people might die over the differences.

My father, now 84 years old, is in some ways busier than ever: traveling with my stepmother, visiting grandchildren across the country, dealing with the difficult details of downsizing from the five-bedroom suburban home we grew up in. He says now he sometimes uses dal powder for convenience, and he’s even seen a mixture of different dals that come packaged together in the Indian store. To him, these were innovations, but I didn’t want to hear any of that. I wanted OG. I did like hearing that sometimes he adds a pinch of hing (asafetida), yes! An ingredient that sounds like a secret potion.

The floods had come, and all the official warnings were to stay home. It triggered memories of the contradictory marketing of the pandemic, when isolating from others meant making puzzles, playing board games with your partner, taking quiet walks on uncrowded streets, moving to idyllic countryside retreats and making elderflower tea; I hate myself for being on social media then. I couldn’t turn away from the devastation, and in Los Angeles the forest fires only added to this constant feeling of threat to our physical spaces and our bodies.

The onslaught of rain this weekend gave me similar pangs of unease. And of course, it was anything but the rain. It was February, and I still didn’t know what my resolutions were for the year. I was feeling off balance with work and exercise. I desperately needed something grounding and substantial.

I needed to make dal. And I needed to bulk it up. Definitely tomatoes and maybe even spinach in the mix. I pulled my dad’s recipe up on my laptop on the kitchen counter: this was going to be a combination of his instructions, my instinct and experimentation, memories of how my grandmother and grand aunt made it, and a second google-searched recipe online that I grabbed some good ideas out of, specifically the ground spices my father left out.

As I walked around our small kitchen gathering things, I could hear the shower of rain like pellets on the fiberglass covering we’d installed above the patio. There were sections that hadn’t been filled in all the way and water was leaking in, getting dangerously close to the drum kit and tables and chairs that could tolerate being outdoors most days, but not in these harsh conditions.

I decided to make the dal in one pot and rinsed off the pressure cooker I last used during the pandemic. Even the act of using a pressure cooker feels like, okay we are doing this the real way. It’s heavy and that whistling sound it makes, and the way that knob thing on top shakes and rattles, is jarring and loud and feels like a steam engine is about to explode. My grandmother used a pressure cooker, our grand aunt who lived with us did too. But they also knew what they were doing.

I was out of fresh tomatoes, so I emptied a can of diced roasted tomatoes into the pot. No one had ever told me to do that, but it was in my cupboard. I was too lazy to peel garlic, so I used 2 teaspoons of minced garlic from a jar. The spinach was fresh and plentiful. I included just a touch of the stalks, and I left the leaves really big. For my tadka, I used fenugreek, mustard seeds, and my father’s recommended dried red chilies: 4-5 sizable halves; one broke in half, spilling out its seeds to sizzle in the oil.

Then I remembered the curry leaves. I hadn’t used them in dal before, but I knew they added a special flavor. My aunt Rhoda brought me a stash of fresh dried curry leaves on her last visit from Bangalore. They sat in my fridge for a while shoved way behind the pasta sauce jars and bottles of olives and underneath a tub of tapenade. I went digging for them and threw some in the pot.

Years ago, my father tried to give me the plant that grows these leaves, a curry patha plant. He tried several times. It’s a sentimental thing because his plant in New York comes from a cutting of a plant from his brother’s house in New Orleans, which comes from a plant in India. My sister in Brooklyn and even my cousin in Minneapolis grow descendants of this common mother. Everyone’s curry patha plants have blossomed, providing year-round leaves for cooking. My efforts to cultivate the plant were not so successful.

The first time my father tried to give me this plant, my son was three and my father, visiting from across the country, lovingly brought a cutting from this ancestral curry patha plant for us to grow. The weather in Los Angeles seemed ideal enough year-round, not like on the East Coast, so he suggested we plant it outside under the small lemon tree in my backyard. My son called it “plantie” and would check on it every day. Barely a week in, the gardeners came and tragically mowed over it.

On my father’s next trip, he brought another cutting of the same curry patha plant. This time, we put a ring of rocks around it to circle it off. A couple of weeks later it was gone too! The gardener had plucked it out by hand thinking it was a weed. My father, unbowed, sent a third plant. This time, by Fedex. The little plant came in a small plastic pot. I spoke to my gardener and explained everything that had happened before and asked him kindly if he’d plant this one again for me; I didn’t trust my own gardening skills. He did and many weeks went by, but the plant didn’t grow. We watered it and watched over it, but nothing helped; it slowly withered away. A while later, when we were doing some digging in the area, we discovered it had been planted inside the small plastic pot it came in. It didn’t have the chance to lay down its roots. It had no room to grow.

This was an infertile time in my relationship with my parents. I didn’t take responsibility for anything that happened in my past. I wanted distance, space, to make my own home. During these years, I was revisiting my own immigrant story. How I came to America with my father as a child but didn’t really have a say in it. How migration separated me from my grandmother in India, whom I loved like a mother. I thrived in the new country but only in terms of what people could see, my achievements in school, my disposition—friendly, outgoing, seemingly confident. What could possibly be wrong?

It would take many decades for me to heal from the violence of being uprooted, from having to watch the first part of my life go up in flames; family members, the home I grew up in, a country and a culture I just assumed would be mine forever, were now cut off and inaccessible except for visits every few years. It would take my becoming an adult and making a home for myself and my young family to fully come to terms with all the ways I’d felt displaced. It took choosing and entrusting Los Angeles to be where we could put down our roots.

I didn’t try to replant the curry leaf tree.

And now, on this rainy night in Los Angeles, I’d found new curry leaves and they were going to be part of my concoction.

A few minutes after the pressure cooker got going, the weight that seals it started rocking back and forth. I had no idea what to do once I turned off the flame. I hesitantly moved the weight a couple of times, and it made a loud forceful sound. Letting off steam. I finally remembered how to release the lid without getting killed, and when I looked inside, I nearly cried out. It looked exactly like I imagined. The roasted tomatoes cooked seamlessly into the blend; the spinach brilliant in its color and smooth in texture, but happily disguised for its taste; the dal, soft, thick, and the perfect color.

I took my first bite. I could taste every ingredient as if each were coming off a crowded train, but there was a flavor that stood out, not dominating, but kind of conducting all the other flavors, keeping them from getting lost in the crowd, holding the other flavors in a gentle lasso. That conductor was the flavor of the curry leaf. I felt a sense of collapse, a melting, a wailing surrender to the perfect notes of these leaves.

I made dal last night. It was a stormy, rainy night in Los Angeles. We didn’t know what tomorrow would bring. I made a version of my father’s dal, which is a version of his mother’s dal. I was aching for the original. What came out was something new; this was now my version. The curry leaves I used were not from some unbroken lineage in my father’s family. They were from a stall in a small market in the neighborhood I grew up in, and had traveled 3,000 miles in the careful clutch of my aunt’s hand luggage. Oceans away from their source, their cultivators’ names lost, in my kitchen they more than blended in; they made my version of dal singular.

To survive in diaspora we need the consolation of a continuous mythology, a story that keeps going, even as it becomes a new story. And so, I believe these leaves have their own kind of magical power. I stir them in. That’s how myth is made.

Indu Subaiya is a writer and entrepreneur based in Los Angeles by way of Bangalore, India. Her essays have appeared in The Rumpus, Stone Canoe, Lunch Ticket, Animal: A Beast of a Literary Magazine, Writing the Resistance, and Immigrant Report. She is an alumnus of the Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation (VONA) writing workshop and received her MFA in creative nonfiction from Antioch University.