Daniel José Older, Author of Shadowshaper

Daniel José Older is the type of writer many of us writers aspire to be—careful, intentional, eminently aware of the ecosystems that produce literary work in our society, and the role this work plays in the context of a predominantly white narrative. His Twitter following is large (sitting at over 22k followers), both because of the quality of his work and because of his willingness to engage with an industry that often ignores the immense diversity of voices—of gender, race, culture, and socio-economic background. Equally excited and intimidated by the prospect of interviewing Daniel, when we spoke on Skype in March 2016, it quickly became clear that my nervousness was unfounded. Daniel is, in the classic sense of the word, engaging. Easy to talk to, but thoughtful in his responses. Careful in choosing his words. Reiterating points that I fumbled with my first questions, my voice cracking, casting glances at my pre-typed list. But soon our conversation meandered pleasantly. Daniel and I spoke for almost an hour and a half—the topics ranging from the craft of writing to diversity, language, music, politics, and a myriad of others. Which is to say that he has a lot to say, because he thinks about all of it in the context of his writing.

Daniel José Older is the type of writer many of us writers aspire to be—careful, intentional, eminently aware of the ecosystems that produce literary work in our society, and the role this work plays in the context of a predominantly white narrative. His Twitter following is large (sitting at over 22k followers), both because of the quality of his work and because of his willingness to engage with an industry that often ignores the immense diversity of voices—of gender, race, culture, and socio-economic background. Equally excited and intimidated by the prospect of interviewing Daniel, when we spoke on Skype in March 2016, it quickly became clear that my nervousness was unfounded. Daniel is, in the classic sense of the word, engaging. Easy to talk to, but thoughtful in his responses. Careful in choosing his words. Reiterating points that I fumbled with my first questions, my voice cracking, casting glances at my pre-typed list. But soon our conversation meandered pleasantly. Daniel and I spoke for almost an hour and a half—the topics ranging from the craft of writing to diversity, language, music, politics, and a myriad of others. Which is to say that he has a lot to say, because he thinks about all of it in the context of his writing.

* * *

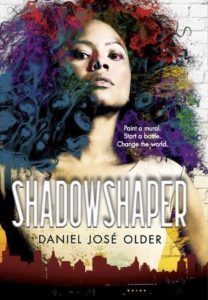

I ask Daniel about the genesis of Shadowshaper, his recently published Young Adult novel, now a New York Times bestseller: whether he had always intended to write it as a YA novel or if it had simply evolved that way. He nods and tells me, “Shadowshaper was the first book I ever sat down to write.” He cites the Harry Potter books as influences for the novel. In 2009, when he began writing Shadowshaper, Daniel had already been working as a paramedic for seven years; he was also working as an activist and community organizer, interacting with young people and organizing marches. And so, between working with black and brown kids, and not seeing himself in the YA books he was reading, the kids not seeing themselves in the books they were reading, he thought, man this is dumb. “A lot of it was in the vein of counter-narrative. What if Harry Potter was to be mixed with The Wire, with characters that speak to us in genuine ways?” But it wasn’t simply about painting Harry Potter in brown face; it’s about world-building. Daniel pauses to make sure I understand, “Don’t get me wrong. I love Harry Potter. [JK Rowling] uses European mythology for her books because that’s what she knows.” The problem, he explains, isn’t that Harry Potter is white; it’s that there are, or were, few other options available. “I want to read a fantasy novel that has inside jokes for me, about my mythology.” And he wrote Shadowshaper as a counter-narrative to the predominantly white fantasy worlds that had been constructed up to then, as a nod to cultures that, up to then (and now) have seldom appeared in fantasy novels.

Brooklyn as a setting, as a basis for the world-building upon which Daniel embarks in Shadowshaper (and his other works), is the perfect backdrop—with its mishmash of cultures, of people trying to understand their places in the community. Out of this world arises Sierra, the book’s protagonist, who Daniel says emerged as a product of her environment—a strong, dark-skinned brown girl attempting to navigate her culture and the complex ecosystem of Brooklyn, and the various shades of brown the place embodies. Again, not a simple task, but one that is clearly worthwhile. “I had to ask myself, am I writer enough to tackle this character,” Daniel says, “and then I jumped in.” And, as with many of his characters, Daniel writes Sierra with nuance, confronting the difficult issues that young brown girls in Brooklyn face. In one scene, Sierra examines herself in the mirror—her dark skin and unruly afro—and grapples with conventional ideas of beauty. It becomes clear that these ideas have woven themselves into her psyche but, thread by thread, she disentangles herself from them, redefines what beauty means, and recognizes the power she carries in her appearance.

Brooklyn as a setting, as a basis for the world-building upon which Daniel embarks in Shadowshaper (and his other works), is the perfect backdrop—with its mishmash of cultures, of people trying to understand their places in the community. Out of this world arises Sierra, the book’s protagonist, who Daniel says emerged as a product of her environment—a strong, dark-skinned brown girl attempting to navigate her culture and the complex ecosystem of Brooklyn, and the various shades of brown the place embodies. Again, not a simple task, but one that is clearly worthwhile. “I had to ask myself, am I writer enough to tackle this character,” Daniel says, “and then I jumped in.” And, as with many of his characters, Daniel writes Sierra with nuance, confronting the difficult issues that young brown girls in Brooklyn face. In one scene, Sierra examines herself in the mirror—her dark skin and unruly afro—and grapples with conventional ideas of beauty. It becomes clear that these ideas have woven themselves into her psyche but, thread by thread, she disentangles herself from them, redefines what beauty means, and recognizes the power she carries in her appearance.

In another scene, Sierra confronts her aunt, Tía Rosa, who spouts racist remarks in her direction about the skin color of a boy she likes. About Sierra’s own supposedly disheveled appearance. At one point, Tía Rosa uses the expression “lighter than the bottom of your foot”—as a sort of insidious benchmark for the color of one’s skin considered respectable, especially for a potential mate. This line illustrates that white supremacy does not just come from white people; it is so pervasive that it weaves itself into brown and black cultures as well. Sierra, in a tense scene of familial confrontation, talks back to her aunt and puts an end to the conversation. It is one of the many scenes in which Sierra asserts herself, empowers herself. What’s amazing, Daniel tells me, is how much international feedback he got from that one scene. “Not just from black and brown communities. Indian communities, Asian communities. So many different people around the world have heard that expression, lighter than the bottom of your foot.” It’s horrifying how many people have heard that, he explains. “Everybody has a Tía Rosa,” he adds.

It becomes clear that these ideas have woven themselves into her psyche but, thread by thread, she disentangles herself from them, redefines what beauty means, and recognizes the power she carries in her appearance.

In Shadowshaper, there is a passage in which Sierra stares at her reflection in the mirror, teasing out her hair, watching the light reflect off her skin. She considers everything people have told her about appearance—her hair, her skin, and her nose—how unkind and unforgiving they have been. She eventually says, “I’m Sierra Maria Santiago. I am what I am. Enough.” This is the type of power with which Daniel imbues his sometimes vulnerable and confused protagonist—an important reminder for young adults of color who seek their own experiences in the novel of the power that they can wield over their self-identity.

Of course, the world of Shadowshaper is filled much more than the weight of oppression. Sierra and her group of friends provide a vehicle for Daniel to explore bigger questions of culture while they hang out, cut up, shoot the shit. Because what teenagers do, and do so well, is rag on each other, try on different ideas, make mistakes, try again. “There’s a great literature to the way that young folks speak to each other. There’s a power to their what I call poetic vernacular.” And though they challenge each other and question each other, their love for one other is never in doubt—this, too, is a form of power. Daniel and I speak about a scene in Shadowshaper where Sierra and her friends visit an overpriced coffee shop that has popped up in their neighborhood—the quintessential symbol of gentrification. In the scene, the friends hit the pause button for a moment on the magical, insidious shit happening around them. They take the opportunity (or rather, Daniel lends them the opportunity) to think about ancestry and its definitions. Spanish versus Latino. Anthropology. Culture. “On the one hand I just wanted to have teens cutting up, because they do that so well. . . On the other hand, [I wanted] to provide them with an antidote to the adults who are trying to put them into boxes, to prescribe to them who they’re supposed date and be, and how they identify. And they’re just saying, you know, I’ma write a book about white people!”

The problem isn’t that Harry Potter is white; it’s that there are, or were, few other options available. “I want to read a fantasy novel that has inside jokes for me, about my mythology.”

Daniel’s work, from his Bone Street Rumba urban fantasy series to Shadowshaper, all exhibit the very diversity he seeks to foment in the publishing industry. He led a petition to replace H.P. Lovecraft’s image for the World Fantasy awards with that of Octavia Butler. His Buzzfeed essay, “Diversity Is Not Enough: Race, Power, Publishing,” garnered a lot of public attention for good reason—it is a scathing critique of the state of the publishing industry, but also provides concrete solutions. It is the type of essay that sparks real, substantive conversation. Older is more than a writer—he is a musician, a paramedic, a fantasy nerd, and, most importantly an activist. “You know,” he says, “I was an activist before a writer. And I was a writer before I was an activist.” He is both, of course. His is the perfect case study of a writer wearing many, meaningful hats.

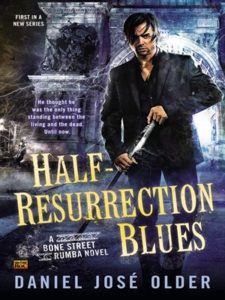

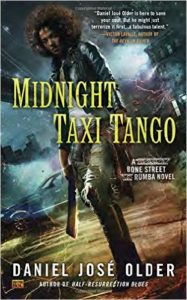

When I ask Daniel about what he read as a kid, in an effort to understand where he developed his unique voice, he cites a litany of influences. He calls himself a definite “sci-fi fantasy kid” (giving a nod to Dune, Star Wars, and Lord of the Rings) but adds that, growing up, he also really loved mythology. “Mythology was my shit. My favorite book when I was a kid was The Iliad.” Indeed, his work seems to borrow from mythology a seamlessness (a word he uses repeatedly when we speak), the casual nature with which gods, spirits, and ghouls interact with everyday people. He also admires the ways in which myths build a universe. “It’s never just the one story,” he explains. “The story fits into this giant framework”—another hint about the way in which Older’s storytelling mind constructs the world his novels occupy. His characters (mystical and human alike) are thrust into situations, building the canon of their experience and adding to the richness of their being. His work, particularly the Bone Street Rumba series—which currently consists of the novels Half-Resurrection Blues and Midnight Taxi Tango; Battle Hill Bolero is due out in January 2017—build just this sort of cohesive, magical world. It consists of a series of vignettes, some of which have been published by Tor as short stories, that all serve to expand the realm through which his characters move.

When I ask Daniel about what he read as a kid, in an effort to understand where he developed his unique voice, he cites a litany of influences. He calls himself a definite “sci-fi fantasy kid” (giving a nod to Dune, Star Wars, and Lord of the Rings) but adds that, growing up, he also really loved mythology. “Mythology was my shit. My favorite book when I was a kid was The Iliad.” Indeed, his work seems to borrow from mythology a seamlessness (a word he uses repeatedly when we speak), the casual nature with which gods, spirits, and ghouls interact with everyday people. He also admires the ways in which myths build a universe. “It’s never just the one story,” he explains. “The story fits into this giant framework”—another hint about the way in which Older’s storytelling mind constructs the world his novels occupy. His characters (mystical and human alike) are thrust into situations, building the canon of their experience and adding to the richness of their being. His work, particularly the Bone Street Rumba series—which currently consists of the novels Half-Resurrection Blues and Midnight Taxi Tango; Battle Hill Bolero is due out in January 2017—build just this sort of cohesive, magical world. It consists of a series of vignettes, some of which have been published by Tor as short stories, that all serve to expand the realm through which his characters move.

“And then,” says Older, “I went to college and put that stuff down.” That stuff, of course, refers to sci-fi and fantasy. There was a period in which he studied nonfiction, and genuinely believed he would end up writing essays. “You know, the folks I admired were Eduardo Galeano, James Baldwin, bell hooks. And I thought shit, if I could do that, that would be amazing.” He ultimately returned to his first loves of sci-fi and fantasy, but not before taking a long detour as a paramedic, a musician, and an activist. What comes across in my conversation with Daniel is the importance he ascribes to living a life, and not just being an observer. “I felt like I needed to put myself into the thick of things, and have something to write about besides theory. . . I think writers can fall into this trap of thinking we are outside of things. I didn’t want to play into that.” His twenties were full of just this sort of living; Daniel thrust himself into the thick of things and set aside writing for a time—though he did write in the back of ambulances about the people he encountered as a paramedic (a career that lasted a decade and produced a series of vignettes called Ambulance Stories). He composed and played music as part of the Brooklyn-based soul quartet Ghost Star. In short, he did things, lots of things, all the while keeping one eye on his activist and writing goals.

…white supremacy does not just come from white people; it is so pervasive that it weaves itself into brown and black cultures as well…

Then, Octavia Butler happened, and it all seemed to click. Daniel sits up when he tells me, “It was really Octavia Butler that brought me back into thinking about fantasy again, because she does it in a way that’s so complicated. She thinks about power so deeply in her stories, but they’re still really great stories. And I was like, oh you can do this power analysis shit in the middle of really deep storytelling.” He explains that the reason this truth came as a revelation to him is that all of the fantasy that he’d been reading up to that point contained white supremacist undertones—whether that be in the form of the white savior, global destruction, or any number of tropes the dominant narratives pushes. But Octavia Butler showed him the possibility that fantasy could tear away at traditional power structures while simultaneously telling good stories. It’s safe to say that Older has taken this inspiration and run with it. In fact, he explains, this focus on the telling of stories in careful, nuanced ways that avoid the pitfalls of classic fantasy tales provides him with a platform to elevate long-marginalized voices, particularly in the fantasy genre. He uses this same platform to publish critical articles about the publishing industry’s status quo.

I ask Daniel about his role as gatekeeper—gatekeeper between the predominantly white lit fantasy writer world and that of the writers of color. He cites Octavia Butler’s influence again. “You know, people of color love science fiction and fantasy, in general . . . but we’re not usually included in the masses of sci-fi fans. . . Butler was one of the first fantasy and sci-fi writers to bridge that gap, and step into really talking to a whole other realm of folks (people of color) . . . and she did it not because she’s black, but because she’s willing to talk about race and power in a really deep way, in a way white writers are not.”

I ask Daniel about his role as gatekeeper—gatekeeper between the predominantly white lit fantasy writer world and that of the writers of color. He cites Octavia Butler’s influence again. “You know, people of color love science fiction and fantasy, in general . . . but we’re not usually included in the masses of sci-fi fans. . . Butler was one of the first fantasy and sci-fi writers to bridge that gap, and step into really talking to a whole other realm of folks (people of color) . . . and she did it not because she’s black, but because she’s willing to talk about race and power in a really deep way, in a way white writers are not.”

Daniel is a gifted writer whose novels embody all of the characteristics of good storytelling: rich characters, epic plotlines, and some of the best dialogue I’ve ever read. His characters jump off the page without relying on archetype, bucking racial stereotypes in favor of depth and complexity. His plots, often grand and steeped in mythology are grounded by the realness of his characters and sweep the reader along. His dialogue is sparse and powerful. Shadowshaper is carefully constructed. Its sights are aimed squarely at issues of culture, appropriation, and colonialism. Its tagline hints at the unapologetic grandness towards which it aspires, which is exactly the sort of grandness young readers are drawn to: Draw a Mural. Change the World. As with much of his work, in Shadowshaper Older seeks to find truth at the intersections of cultures, of spirits, and even of life and death. He draws on old mythologies, finding modern twists and blending them with the reality of living marginalized—but empowered—in today’s world. What’s more, the cast of characters in his work, from the Bone Street Rumba series to Shadowshaper, are all rich in their nuance and diversity.

I needed to put myself into the thick of things, and have something to write about besides theory. . . I think writers can fall into this trap of thinking we are outside of things. I didn’t want to play into that.

Along these same lines—of giving voice to the traditionally overlooked—Older embraces polyvocality. In Midnight Taxi Tango, he writes from the perspective of several very different characters: Carlos, a half-dead (possibly) Puerto Rican man with no memory of his past life; Kia, a stubborn and self-empowered black girl; Reza, a queer woman of color who never leaves home without at least a couple of guns. Writing the Other is, of course, not an easy task. Playing the devil’s advocate, I ask Daniel how he can do this—that is, write the Other—when it is so difficult to write experiences that one hasn’t personally lived. “That a complicated question,” Older tells me. I apologize. He shakes his head and says, “I’m not here for the easy ones.” He adds, “you can’t write and not write the Other. You’ll have very boring books with one character. It’s a memoir. But here’s the thing: it shouldn’t be too much to ask that it be done right. And the problem is that it’s not usually done right. It’s usually done very poorly, and that needs to be part of the conversation. Otherwise it just becomes well, you asked for diversity so we gave you a black bad guy!” The problem, as Daniel sees it, is not necessarily that there is a lack of diverse characters in novels nowadays (he sees progress on this front), but that the conversation seems to have stopped there. That the publishing industry seems willing to hang a banner on this accomplishment and call it a day. The next step, then, is to build characters that are true to life. To write these characters not as tropes, but as living, breathing beings.

From this, our conversation veers naturally to a discussion of one of the characters in Shadowshaper, Wick, a white anthropologist who attempts to study the protagonist Sierra’s Caribbean ancestry and, ultimately, to harness its magic. Wick’s intentions are good—initially he wants merely to act as chronicler, as preserver, but he soon begins to wield the power for himself. There are many notable questions surrounding this character, one of which Sierra herself asks: who gets to study whom? Why is it that this white man gets to play scientist with her culture and that of her ancestors? And more importantly, do his intentions matter? That is, do his benevolent aspirations do anything to dull the decidedly colonialist nature of his actions? The answer is no, of course. Daniel tells me that “a piece of Wick’s whole problem is that he doesn’t fully understand the powers around him.” He is participating in this centuries-long battle, of which he understands almost nothing. There is a clear parallel here to what humans do, particularly those belonging to a dominant class, and a call to more fully grasp one’s role in the grander narrative, both literary and otherwise.

Older seeks to find truth at the intersections of cultures, of spirits, and even of life and death. He draws on old mythologies, finding modern twists and blending them with the reality of living marginalized—but empowered—in today’s world.

“It’s never about you,” he says, when our discussion shifts to gentrification—a rampant problem in both my adopted city of San Francisco and Daniel’s home in Brooklyn, and in many urban areas across the U.S. It’s a topic about which everyone seems to have a strong opinion. Unsurprisingly, Daniel’s thoughts on the matter are carefully thought out. “When I wrote about gentrification for Salon, a lot of the response was well what am I supposed to do about it? And it’s never been about how this individual person shouldn’t do that. It’s about: are you aware of the power framework that’s functioning through you when you make a move. And then do you have that in mind so that you can understand it and react to it? Are you conscious of your relationship with the police, with real estate people?” And therein lies the heart of the problem. Many people who move through life, even allies (most notably allies), are, despite their good intentions, unaware of the space they occupy within a system that aims, intentionally or otherwise, to marginalize. This is a profoundly uncomfortable topic of conversation for white people. For cisgendered people. For men. For those who do not need to consider their place because it is the default. But, the uncomfortable conversation is precisely the one that needs to be had, especially for writers, and it is precisely why the Wick character exists. Daniel explains to me that Wick was originally written as a prototypical bad guy monster (big teeth, scary), but he changed him to the more nuanced, profoundly human, well-intentioned, but ultimately doomed-to-fail character he eventually became. Daniel tells me that “great writers should be the first people to dive into layered conversations. That’s the thing that literature is supposed to do. Talk about uncomfortable shit. That’s your job. Why would you miss that opportunity?” Daniel lives with this discomfort. His work lives in that fraught space because that’s where all of the change happens—and all of the best literature. Avoiding the difficult or accepting the erasure of marginalized communities does nothing to make things better.

The problem, as Daniel sees it, is not necessarily that there is a lack of diverse characters in novels nowadays (he sees progress on this front), but that the conversation seems to have stopped there. That the publishing industry seems willing to hang a banner on this accomplishment and call it a day.

Our conversation meanders again to the idea of the “issues book.” I ask—“so is that why you wrote Shadowshaper as a YA novel? So that you could tackle these questions of race and white supremacy.” Daniel pushes back against my white person question. He explains the concept of “the issues book”—unsurprisingly, a book that is predominantly about one issue. Race, for example. “There will be subplots, characters might fall in love, but at the end of the day it’s about this one. . . whatever.” Though he doesn’t disparage any individual book for this approach, Daniel questions the overall concept. “People of color, or anyone who deals with any kind of oppression, walks through life every day multitasking. It’s not like everything else stops so that they can deal with that oppression. You’re trying to pass the SATs, and you’re getting hit on the street, and you’re being told you’re ‘less than’ by your teacher. All these things are happening at once, and you have to multitask to survive.” This point is particularly salient in Daniel’s novels, particularly Shadowshaper, because all of these things are happening in concurrence with threats from zombies, ghosts, and all manner of evil spirits. In Shadowshaper, Sierra fights zombies, anti-blackness, street harassment, her grandfather’s patriarchy. All of these facets of Sierra’s reality bring depth to the world in which Sierra lives, and they are a true representation of the black and Latino experience. “It’s not just a bunch of outlying moments of bad shit happening. They’re all in conversation. They’re all related. Even if the book doesn’t explicitly tie it all together, if I’ve done my job you walk away seeing that there are these connections between the different conflicts.” All of this is to say that Daniel’s approach to writing, as it is to living, is holistic.

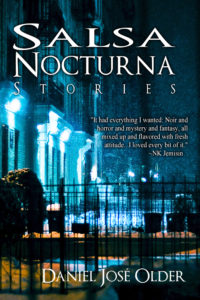

One particular aspect of Daniel’s writing that stood out to me is the musicality of it. Not in the sense of the musicality of the prose (though that too) but his willingness to use music as the glue between his stories. Unlike many writers, though, he does not reference popular bands, or even real bands. Instead, Daniel invents and describes music specifically for the novel in which it appears—another example of his ambitious world-building techniques. In fact, the music he composes crosses the boundaries of his novels—Kia, one of the main characters of the Bone Street Rumba series often listens to King Impervious, who is actually the character Izzy from Shadowshaper, one of Sierra’s inner circle of friends. In Salsa Nocturna, one of Daniel’s early collections, music appears that also emerges in his later works. In essence, Daniel constructs, in his world, a sort of literary score. When I ask him about this, Daniel smiles broadly. “It’s more fun that way!” he says, “You get to make your own music!” I ask him about Sierra’s brother’s band, Culebra, a thrash metal salsa band. In Shadowshaper, Culebra acts as a sort of character in its own right, joining the ancestral and contemporary. “It’s based on a Mars Volta song (L’Via L’Viaquez),” Daniel tells me. “I heard it one day at Newbury Comics with my mom, and we were both like what the fuck is this?! And so we bought that album. And that became Culebra.” As a Mars Volta fan, I am ecstatic when he says this, but it also clicks for me that of course Culebra is The Mars Volta—because he describes their music with such intense detail. He does the same with a particular song in Half-Resurrection Blues, too, as he describes the music at the cusp of a burgeoning love between two of the protagonists. Amid a flurry of poetic prose, the reader is lost in the notes. Daniel tells me that the description of the song seems to have resonated with readers so much that people often tweet at him demanding its name. He shrugs and tries to explain. “I made that shit up!”

One particular aspect of Daniel’s writing that stood out to me is the musicality of it. Not in the sense of the musicality of the prose (though that too) but his willingness to use music as the glue between his stories. Unlike many writers, though, he does not reference popular bands, or even real bands. Instead, Daniel invents and describes music specifically for the novel in which it appears—another example of his ambitious world-building techniques. In fact, the music he composes crosses the boundaries of his novels—Kia, one of the main characters of the Bone Street Rumba series often listens to King Impervious, who is actually the character Izzy from Shadowshaper, one of Sierra’s inner circle of friends. In Salsa Nocturna, one of Daniel’s early collections, music appears that also emerges in his later works. In essence, Daniel constructs, in his world, a sort of literary score. When I ask him about this, Daniel smiles broadly. “It’s more fun that way!” he says, “You get to make your own music!” I ask him about Sierra’s brother’s band, Culebra, a thrash metal salsa band. In Shadowshaper, Culebra acts as a sort of character in its own right, joining the ancestral and contemporary. “It’s based on a Mars Volta song (L’Via L’Viaquez),” Daniel tells me. “I heard it one day at Newbury Comics with my mom, and we were both like what the fuck is this?! And so we bought that album. And that became Culebra.” As a Mars Volta fan, I am ecstatic when he says this, but it also clicks for me that of course Culebra is The Mars Volta—because he describes their music with such intense detail. He does the same with a particular song in Half-Resurrection Blues, too, as he describes the music at the cusp of a burgeoning love between two of the protagonists. Amid a flurry of poetic prose, the reader is lost in the notes. Daniel tells me that the description of the song seems to have resonated with readers so much that people often tweet at him demanding its name. He shrugs and tries to explain. “I made that shit up!”

Great writers should be the first people to dive into layered conversations. That’s the thing that literature is supposed to do. Talk about uncomfortable shit. That’s your job. Why would you miss that opportunity?

We talk about the publishing world, and how the publishing industry, while making strides in the right direction, is not yet willing to be publicly open about race. “We’re still not in a place where people in the publishing industry, in general, are being brave in their public dialogue about this. Diversity is a really nice word to say, but it doesn’t mean anything. . . you have an amazing diversity of whiteness, but people of color still only get to be that one singular person who made it through the gauntlet into the future.” In short, we are part of the way there. We are having the discussion and this is encouraging, but there is a lot of work left to do. We need editors of color. Agents of color. Acquisitions editors of color. It’s an entire ecosystem shift that the literary world requires—not simple tolerance of alternative narratives. Because the industry still frames these narratives as alternatives rather than one of a multitude of voices.

Near the end of our interview, I ask Daniel my standard guilty-liberal question. What can I do, as an editor, to make things better? After a hearty laugh, he tells me it can be as simple as diversifying who you’re watching, particularly in online spaces like Twitter. It takes some sifting, of course—not everything you see on Twitter is worthwhile. But, he tells me that, after a while, “you start to see whose voices the people are lifting up.” He points me at publications that espouse the principles of diversity, like Seven Scribes, Catapult, and Fireside Fiction (for which Daniel has recently begun editing), and encourages me to follow the works that emerge from such publications. Daniel explains to me that, as an editor, you have to solicit work from writers of color. It’s not enough to simply state “diversity” as a goal. “Writers of color have no reason to trust majority white publications.”

Near the end of our interview, I ask Daniel my standard guilty-liberal question. What can I do, as an editor, to make things better? After a hearty laugh, he tells me it can be as simple as diversifying who you’re watching, particularly in online spaces like Twitter. It takes some sifting, of course—not everything you see on Twitter is worthwhile. But, he tells me that, after a while, “you start to see whose voices the people are lifting up.” He points me at publications that espouse the principles of diversity, like Seven Scribes, Catapult, and Fireside Fiction (for which Daniel has recently begun editing), and encourages me to follow the works that emerge from such publications. Daniel explains to me that, as an editor, you have to solicit work from writers of color. It’s not enough to simply state “diversity” as a goal. “Writers of color have no reason to trust majority white publications.”

My conversation with Daniel concludes with a discussion on the use of italics for foreign words—a rule with which Daniel strongly disagrees, and one we at Lunch Ticket have agonized over. MLA standard says to italicize non-English words. Writers who code-switch don’t like to do so. Daniel becomes animated during this discussion. He clarifies his position for me: “There’s a functionality to language that matters much more than any sort of rules and regulations. Italics do not help with clarity, they confuse things.” Daniel tells me that the rules surrounding the use of language should reflect their usage, not dictate it. “Language is a living, fluid, complex, and ever-changing entity that comes from us. In some ways you can think of it as one of the great democracies, but only if you treat it that way.” In a way, this thought embodies the very nature of Daniel’s thinking—that writing can be a power for good, but only if it’s done carefully, and with intentionality.