Excerpts from Singing Through Clenched Teeth

Midnight (1949)

Like frightened birds

after a hunter’s shot—

My dreams scatter in flight

when I open up my eyes…

My reveries, return to me,

I beg of you, I plead,

I command you!

But the empty distance echoes:

Who, who…

You—in the night,

with whom you persist

all alone.

You—the one who cannot hear, do you trust it?

Clearly whatever may come of you

is all the same to it.

Today that is the striking

of desperate fists

in its thicket:

“Why?” “Why?”

The Saucer in the Sky

The saucer in the sky,

that you promised me,

show me the stone,

where you smashed it into pieces.

And the mountains, the golden mountains,

which I forgave you,

where have they escaped to,

tell me, in which streams of smoke?

I have not broken

the saucer in the sky,

I have fallen and been beaten

down to my feet and through my bones,

And the mountains, the golden mountains,

they flew off in all directions,

when I only made the slightest try

to open wide my eyes.

Come to My Dream

No greeting, no sound,

of you I’ve had no dream…

Who then has been stationed

right at the entrance

to my sleep?

I’m sinking downwards like death

from fatigue, from the cold,

who then has been stationed

right at the threshold

of my fantasies?

A thought from somewhere

breaks forth from its chains,

makes a flash in the silence:

Make way to your dreams,

make way to your dreams!

But my nightly entreaty,

doesn’t succeed, it would seem,

so who has stood guard

at the edge of my dreams?

The KGB.

When My Love Goes to Sleep…

Sleep, my dearest,

go to sleep!

I will be rolling stones up peaks,

I will be bearing chains alone—

You, however, should blissful be,

my distant dearest,

my distant sweet…

Better that you not remember

those days and nights in ember,

when we were full of pleasure…

Sleep, my dearest,

go to sleep!

May you be cherished by your faithful lover,

may you be his only fire,

as once you were for only me!

Over me—the borealis.

Under me—the earth is darkness…

Still, my heart—no need to murmur—

Sleep my dearest,

go to sleep,

my distant dearest,

my distant sweet.

*

Polished in blood and flame,

washed in tears,

God willing, you might, my sweet,

just this once be clean!

The same fields mourn,

the same heavens freeze,

the same ears yearn,

the same—the uniforms.

And the eyes, too, bore

in from the other side,

and the terrors, too, lie in wait

on all your ways away.

But times, they say, do change—

the skies are now in tatters,

the faraway places are already others,

and different too—the distances.

And the Caucuses can no longer

help with all their hills and crevices

a poet find his shelter

from these ferocious police searches.

Spring (1956)

The sky and the forest

the people and the streets

are moving

in the wave-like whirl

of the water.

And the old truth

blooms anew in me

that every little thing—

grows smooth and clear in the current.

Through pain kept secret,

and through muffled weeping

I recite to myself

a prayer or a speech:

There is no joy to be found,

when water is still.

Flow, water, flow

in good health!

Emerging

I am emerging to a blinding evening—

Perhaps you were calling, or did it only seem?

I am departing on a rushing day—

Perhaps you caught wind of my weeping from so far away?

The cities are spinning and people are teeming

And the fiery cogs of time’s wheels are turning.

The millstones are milling, the cleaver is cleaving—

Day after night and night after day!

But let your voice at least be heard from afar,

let me feel your weight on my shoulders.

And stay—I will stay, this I alone know,

I am stronger than iron, I am harder than stone,

I burn up flame and freeze over frost

and as I sprout forth like the grass I split open rock.

From Afar

Better —if my tormented tears—

could fatten your fields,

better—if I could be the stone,

you could hurl me at your foes.

Better—if I could be the sand,

or the desert’s withered thorn,

better if I could be the venom,

your fury’s deadly curse—

Better than life, better than wandering far from home

and with a burning tongue in my mouth,

when longing arrives like a bear and digs in its claws

and buckles my knees…

August 12th, 1952 [Night of the Murdered Poets]

On this very day,

on this very day

the pain and the weeping

multiplied the prison bars.

The pain—in the heart,

the lament—through clenched teeth:

Bergelson, Markish, Kvitko, and Hofshteyn.

They were felled

in the middle of the night

and no one brought them any solace

before death.

And the only light

that anointed them at the end

came right at the flash

of the murderous volley…

On this day,

on this very day,

I raise up

and I carry

my song spattered with blood—

My poem—a gravestone

my heart— like a candle

but I will not now—

it turns out

fulfill my duty—

There is nowhere to place

any candle nor stone—

Bergelson, Markish, Kvitko, and Hofshteyn.

The Third Day a Bit of Bread

*

On the third day a bit of bread,

surrender the shirt off your back

flay away your own skin,

but don’t remain in foreign lands.

Every smallest shrub will beg you: stay!

Every stone will groan.

Your childhood—with her thin wail

will tear your flesh to pieces.

The local lullaby from your cradle

will turn old and gray,

but go and do not look back

and may it be an auspicious day!

TRANSLATORS’ STATEMENT

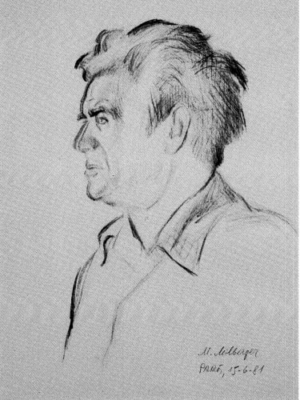

Yoysef Kerler was an important post-war Soviet Yiddish poet. Born in Ukraine in 1918, he published poetry as a young man and studied acting at the Moscow State Yiddish Theater. During WWII, he served with the Red Army, and his first book of poetry consisted of poems written during the war. This would also be the last book of Yiddish poetry Kerler would publish in the Soviet Union. Within a few years, all Yiddish publications were banned and, in 1949, Kerler was arrested. He spent the next six years in the Vorkuta Gulag, north of the Arctic Circle. Upon his release in 1955, he became one of the first prominent refuseniks, Jews trying to leave the Soviet Union for Israel.

The following poems were written in the gulag, as well as likely just before and after Kerler’s release. A number of Kerler’s gulag poems were initially published in Russian translation, disguised as poems about a Nazi ghetto. They were finally published in Yiddish in Israel, after Kerler arrived in the 1970s.

Ironically, Kerler was lucky to have been sentenced to the gulag, as he avoided the fate of many other Yiddish writers who were murdered by Stalin on the infamous “Night of the Murdered Poets” in 1952. He eulogizes them here. The poems from Singing Through Clenched Teeth also document his growing alienation from the Soviet Union—what he called his cradleland—and his increasing longing for Israel, which he began to refer to as his homeland.

Kerler often worked as a lyricist and many of his poems have a strong songlike quality. I find these to be his easiest to translate, though sometimes I wonder if that ease is simply a result of my enjoying them the most. There are terms, such as “saucer in the sky” that conjure up associations in English that are different from those in Yiddish. In English, “saucer in the sky” may sound like a UFO. In Yiddish, to “ask for the saucer in the sky” means to reach for the moon, for the impossible. In context, I have faith that English readers can figure it out.

Eastern European poetry often employs significantly different grammatical norms, with greater use of dashes. These differences are the trickiest aspect of Kerler’s poetry to translate, made more difficult still by the absence of capital letters in the Hebrew alphabet. I try to keep the artful use of dashes by smoothing out the grammar elsewhere, when I can.

Maia Evrona is a poet, memoirist, and translator of Yiddish literature. Her translations of Yoysef Kerler were awarded a fellowship from the Yiddish Book Center, while her translations of Avrom Sutzkever have received fellowships from the NEA and ALTA. In 2019, she was the inaugural recipient of the joint Spain-Greece Fulbright Scholar Award, though her time in Europe would be ill-fated due to COVID-19.

Yoysef Kerler was an important post-war Yiddish poet. Born in Ukraine in 1918, he served with the Red Army during WWII. He would later serve five years in the Vorkuta Gulag for so-called “anti-Soviet nationalist activity.” Following his release, he became one of the first prominent refuseniks.