From Paper to the Page

As a writer, I love the process of moving from image to word, collection of disparate sentences to themes, exposition to scene, draft to draft. When I give myself time, I begin this process on a physical, material sheet of paper. More often, I move too quickly. My fingers speed across the keyboard and lose contact with the page. I grow out of shape with my pen. Yet, it seems that the books I’ve been picking up lately are reminding me that if I want to write, really write, I have to do just that: sit down and write. I know I need to, but sometimes getting back in shape can hurt before it feels good again.

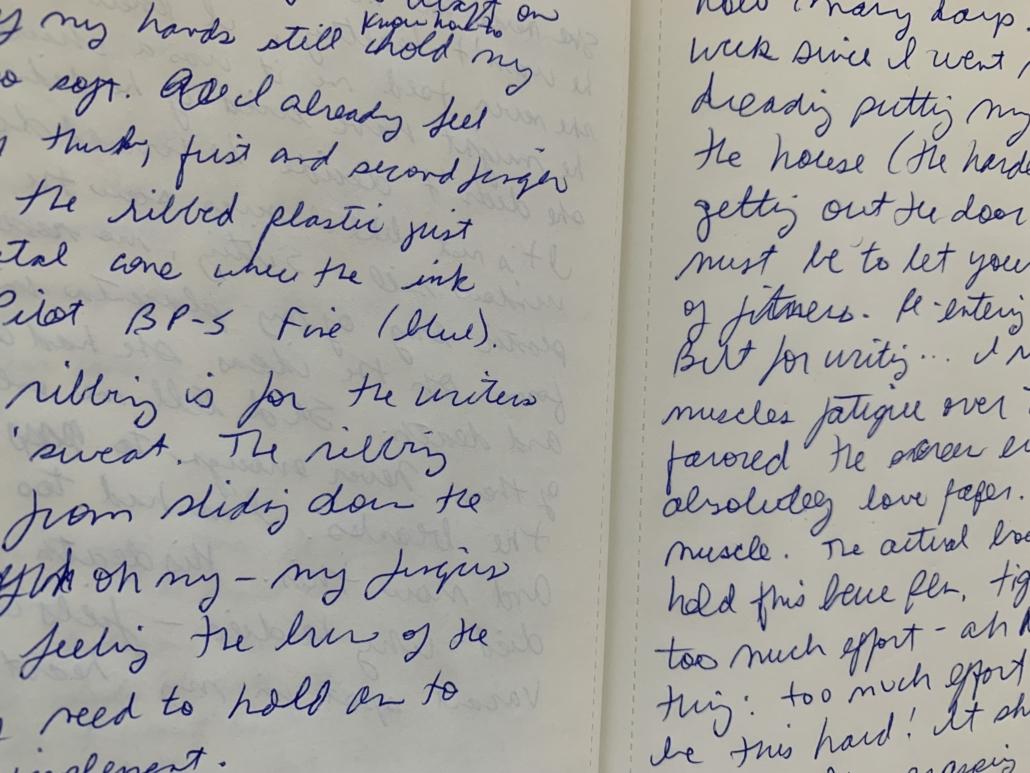

I decided to draft this blog post in my notebook as a low-risk venture. I wanted my hands to remember what it felt like to hold a pen. A blue Pilot ballpoint pen, 0.7 mm. I immediately noticed how soft my fingers were, how quickly they felt bruised from the plastic ribbing of the pen’s grip.

I wanted my nose to remember the smell of paper. Deliciously damp soil. Not the smell of the air molecules rising from the soil beneath the lawn before a rainstorm, rather the smell of the soil blown around during said rainstorm that settles in the cracks of the pavement on a northeastern fall afternoon.

I wanted my brain to remember what it was like to begin a new piece of writing from scratch. From the scratching of my pen across a blank piece of former organic matter. To remember how to pay attention to sensations before trying to type ideas.

Many of us look up to authors who stress the importance of starting first drafts with a writing instrument on a piece of paper. Stephen King, Annie Dillard, Jhumpa Lahiri, Verlyn Klinkenborg, and countless others have taken time out of their great literary careers to write about writing, the process of getting words on the page. We are told of sticky notes, journals, notebooks, margins, collections of scraps. Brilliant prize winning authors tell us their bestsellers wouldn’t exist without their words written on a piece of paper. Even the most recent Nobel Prize winner, Annie Ernaux, wrote in The Paris Review, “For me, words that are set down on paper to capture the thoughts and sensations of any given moment are as irreversible as time – are time itself.”

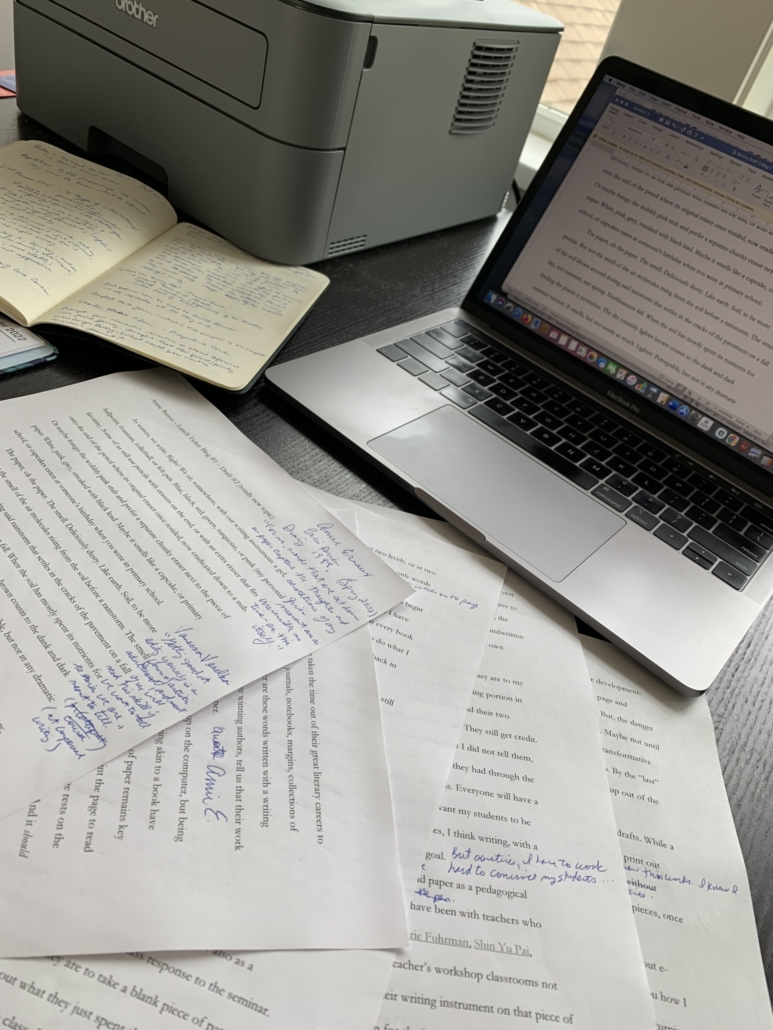

We rarely hear about how those words on the paper end up on the computer. But all words we read in a book (or something akin to one) have been imported in one way or another onto a computer. And yet, the role of paper remains a key component of many writers’ processes. Once these writers have a draft in the computer, they print the page to read it. They hold the printed-out paper in their hands, or on their lap, or maybe it rests on the desk or table or clipboard. Regardless, there is a physical object that can be touched. And it should be touched. No draft should be left untouched.

Lucy Corbin’s excellent chapter, “Material,” in Tin House’s “The Writer’s Notebook,” is one of the more explicitly paper-focused craft essays I have come across. In it, she refers to the page once the words have been imported into the computer and then printed onto a physical piece of paper.

“… your material (words placed variously on paper) can begin to show you what you are trying to say in the story materially (as in content) … The story, I like to say, is always smarter than you – there will be patterns of theme, image, and idea that are much savvier and more complex than you could have come up with on your own. Find them with your marking pens as they emerge in your drafts” (emphasis in original, p. 87).

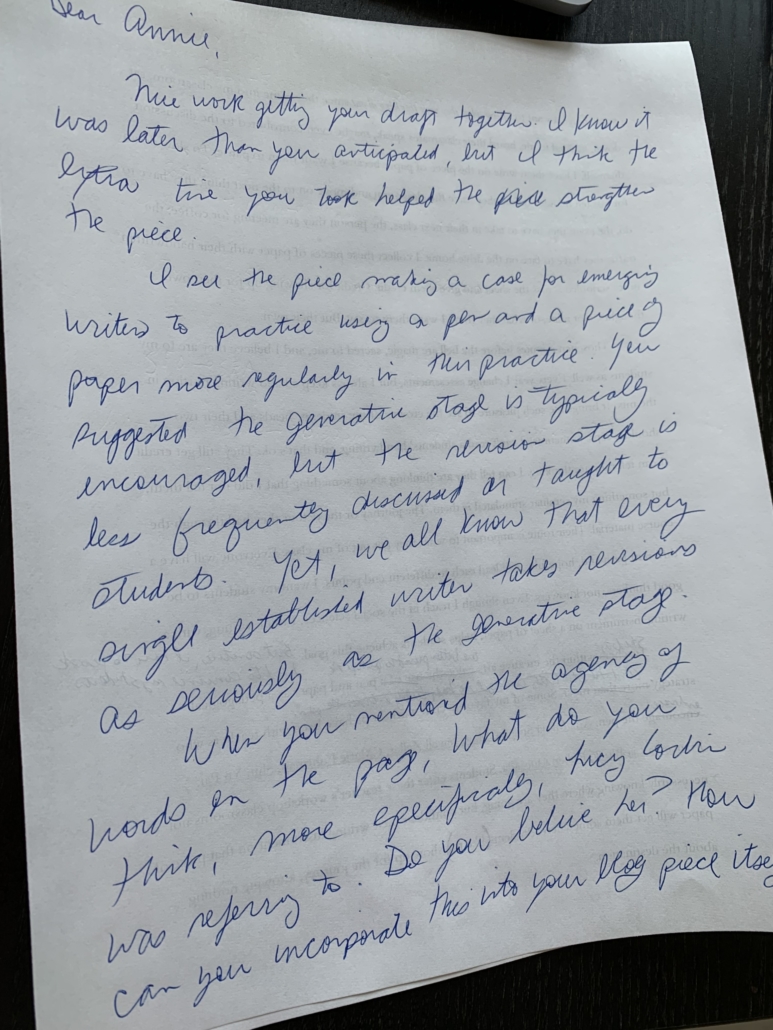

Corbin suggests that the words on the page, once printed and viewed and even altered with scissors, and then moved around, have agency. As if the writer’s words take up a role exclusive to the hand that put them there. As if, once printed out, your words have a chance to tell the story they want to.

I know the value of writing with a piece of paper not only as a writer, but also as a professor. One of the assessments for my graduate level Environmental Management class, “Social Change for Sustainability,” is an in-class response to my two-hour seminar. Ten minutes before the bell rings, students take a blank piece of paper and write (with their hand-held writing instrument). I don’t ask them for a summary of the class. I don’t want them to write their study notes. My only requirement is for them to pause, to slow down for just ten minutes before they leave the classroom and move on to the next thing – the exam in their next class, the person they are meeting for coffee, the traffic they have to face on the drive home. I collect these pieces of paper with their handwritten notes scribbled across the sheet and give them credit. Credit for their words. Not mine, theirs (even if I can’t read their handwriting).

Research suggests that the brain processes ideas and information in different ways when typing or handwriting. On the piece of paper, after class, students write about something my seminar stimulated in them, not something I told them, which is more common when students type notes during seminars. On the piece of paper, students write about their journey, or detour, they had through the course material. They make connections between the course material and the “…material (words placed variously on the page),” à la Corbin. Everyone will have a different path and, hopefully, lead each to different endpoints. Writing by hand helps students become better thinkers and also more proficient in the subject matter. I believe such intellectual diversity and rigor will help us find more creative solutions to entrenched social problems (Ross Gay shares a similar pedagogical philosophy in the November/December 2022 Poets & Writers).

Students within the creative arts are primed to accept the pedagogical value of utilizing a pen and paper. We bring notebooks, journals and marbled composition books enthusiastically to our workshops. Some of my favorite craft seminars have been with teachers who embrace the pen: Ana Maria Spagna, Maya Jewell Zeller, CMarie Fuhrman, Shin Yu Pai, Francesca Lia Block, Ruben Quesada. Students enter these teachers’ classrooms not necessarily knowing where they are going, but confident their writing instrument on that piece of paper will take them somewhere. The power of the piece of paper for these teachers is often in the generation stage of creative writing. Astute students will take their initial ideas scribbled in their own handwriting and massage them into something they can transcribe eventually onto the computer. Yet, once the words are imported onto the screen, they often stay there. At least mine frequently do.

As a published academic author, I should know better. While academic writing is a very different genre from creative writing, they share some overlaps in process. I produce my best work when I give myself time to print it out and scribble and scratch all over the piece. Every article I have published is a result of at least a half-dozen full revisions on a sheet of paper. By that I mean: revising the beginning, middle, and end, at least several times each.

I might print my last creative writing draft onto a physical page, but by that time, the words have lost the transformative agency they might have had earlier in the process, as Corbin suggests they do. By the “last” draft, many of us are often so close to our story that we’re happy to polish, but find cutting it up out of the question. There can be many reasons for such reluctance. For me, my psyche plays with a combination of fear and impatience, which keeps my draft at arm’s length (or keyboard length). The result is that some of my stories’ potential are not fully realized. If I give myself time with my pen, especially in the more “final” stages of the writing process, my work and my outlook are better off.

Luckily, there are resources to help us get un-stuck behind the screen, particularly around editing and revising work you already have on a page. Workshops like Vanessa Veselka’s, offered through Corporeal Writing, helps writers develop self-editorial skills to not only produce better work, but inch closer towards “artistic adulthood.” Textbooks, like Peter Ho Davies’ “The Art of Revision,” offers students advice on getting to know your material, what he calls the “the journey of a story – the story of a story.” Or checkout Catapult’s supportive website for tips. Lyz Mancini, for example, suggests taking revisions a step further and imagining ourselves as readers, not only writers, of our own work. She recommends authors write themselves an editorial letter, such as one you might receive in response to a book proposal. The letter could offer the distance needed to see your work with fresh eyes, and therefore, see your words’ agency.

There are, of course, many other ways you can get back in shape with your pen, to feel less estranged from your page. But like anything you haven’t been practicing, it can be hard to get going again. Even after writing this blog post on the value of writing with a pen on a piece of paper throughout each stage of the writing process, I was tempted to submit it without printing it out one last time. Again, I should know better. So I did. I gave myself time. I printed it out. I scratched my blue Pilot ballpoint 0.7 mm pen all over the seven pages. My fingers are a little less soft this time. My nose picked up the smell of printer fumes more than the smell of organic matter. I see a handful of other ways to revise this blog post from the beginning, middle and end. It is clear that my material has other stories to tell. But those are topics for another time. Until then, this blog post is a gentle warm up to remind my muscles, senses, and brain what it can do. Just a gentle warm up before any heavy lifting.

Annie Bartos is an academic and a writer. She earned her PhD in Human Geography from the University of Washington and is working on her MFA in Creative Nonfiction at Antioch University. She has taught in Geography, Gender Studies, Environmental Management, Global Studies and Comparative History of Ideas at the University of Washington and the University of Auckland in Aotearoa New Zealand. Her work is published or forthcoming across a range of academic journals including Hypatia, Gender, Place and Culture, and Emotion, Space and Society and literary journals including The Sun, The Los Angeles Review, and Pleiades. You can find these and more at www.anniebartos.com