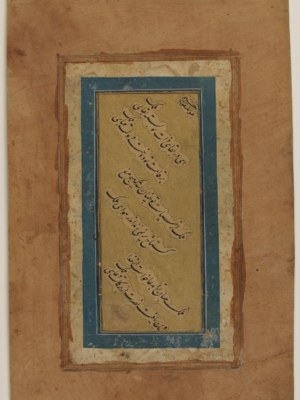

Ghazals of Jahan Malek Khatun

[translated text]

Ghazals of Jahan Malek Khatun (جهان ملک خاتون)

How are you? you ask. How am I without you, my love?

Until morning I swim in the blood of my eyes every night.

You abandoned me. You bloodied my heart.

Then you let me fall from your eyes like tears.

Carelessly, your eyebrows stole my heart.

I’m a captive in your charming eyes and tresses.

I wander in the streets of your absence, alone and hopeless.

Give me back my heart now that won’t unite with me.

Every moment without you is subtracted from my life;

every instant adds grief to the pain of your absence.

His hair draws the heart to desire; on his rubied

lips a kiss will pacify my madness.

He had stature in the world of grace like an aleph: ا;

His absence, though, has bent me like the nun (ن) of my name.

پرسی ز من که چونی ای دوست بی تو چونم

تا روز از دو دیده هر شب میان خونم

خونم ز هجر در دل افکندهای و آنگاه

داری مرا ز دیده چون اشک سرنگونم

ابروی تو به شوخی بربود دل ز دستم

وز چشم و زلف تا کی داری به صد فسونم

تا چند بی دل و یار در کوی هجر گردم

چون نیست وصل ممکن دل باز ده کنونم

هر لحظه بی وصالت از عمر میشود کم

هر دم ز درد هجران غم میشود فزونم

زلفش به سوی سودا دل میکشد ز لعلش

یک بوسه گر دهد یار ساکن شود جنونم

قدی الف صفت بود اندر جهان خوبی

ما را ولی فراقش کردهست همچو نونم

How long will you roll me round myself like a scroll?

How long will you twirl me in your hand like a pen?

How long will you deceive me by what you write and say?

I’m not that ignorant: you know me well.

The goshawk of my union had no place on your shoulder

since you trapped me so lightly to the earth.

How long will you surrender me like dust to the winds,

with my heart on fire, then drown me in my tears?

I knew from the first day that in your love

I’d reap only anguish.

I became the dust of the roads to sit on your robe.

When will you stop shaking me off your lap?

My pain is past patience, stay o my soul, o my world.

As you’re the cure for my pain, for me you’ll endure.

بر مثال نامه بر خود چند پیچانی مرا

چون قلم تا کی به فرق سر بگردانی مرا

چند بفریبی به تقریر و به تحریرم دگر

این چنین نادان نیم آخر تو میدانی مرا

شاهباز وصل ما در دست تو قدری نداشت

کز هوا در دامت آوردی به آسانی مرا

ز آتش دل همچو خاکم چند بر بادم دهی

وز دو دیده در میان آب بنشانی مرا

من هم اول روز دانستم که در سودای تو

حاصلی دیگر نباشد جز پریشانی مرا

خاک ره گشتم که آویزم مگر در دامنت

تا به کی جانا چو گرد از دامن افشانی مرا

دردم از حد رفت بنشین یک دم ای جان و جهان

کاندر این دردم تو درمانی تو درمانی م

Will my beloved be faithful to me? Nope.

Will he stop his cruelty? Nope.

Will he bring mercy upon miserable lovers

for God’s sake? Nope.

Will his cruel hands peacefully ungrasp

the fringe of my pleasure? Nope.

With a joyful remedy, will the saviour of union

redeem us from our pain? Nope.

Will his pearl-scattering lips sweeten

our mouths with his words? Nope.

His Hindu hair steals by profession:

will it forget its origin? Nope.

Will the morning breeze

ever share the beggar’s demand with the king? Nope.

Will the estranged lover kindly

reconcile me with myself? Nope.

Will the affluent one, enthroned on happiness,

remember every hapless wretch? Nope.

Will a man ever see devotion from wealth, pride,

blessing, and success in this world? Nope.

Will I be separated from my love

by the sword of absence in this world? Nope.

يار با ما وفا كند نكند

ترك جور و جفا كند نكند

رحم برعاشقان سرگردان

از براي خدا كند نكند

دست جورم ز دامن عشرت

بي جفايي رها كند نكند

بعلاج طرب طبيب وصال

درد ما را دوا كند نكند

لب گوهرفشان او به سخن

كام ما را روا كند نكند

پيشه زلف هندويش دزديست

اصلْ هرگز خطا كند نكند

حال درويش را نسيم صبا

عرض آن پادشا كند نكند

يارِ بيگانهخوي از سر مهر

با خودم آشنا كند نكند

محتشم بر سرِ سرير نوا

ياد هر بينوا كند نكند

مال و ناز و نعيم و جاه جهان

هيچ با كس وفا كند نكند

در جهان تا منم مرا از دوست

تيغ هجران جدا كند نكند

Jahan Malek Khatun on Women’s Writing

It is not unknown to the learned and to artists that those are wise who do everything they can to leave a trace of their being on the pages of times. Day by day, that trace is covered by the dust of oblivion and the duration of time eliminates its form from memories. Therefore, it is necessary to build a work—a monument—that causes the name to endure after the body decays. It is obvious to all who are wise that the foundation of speech will not be demolished by tempestuous events. Its trace will never disappear from the page of the days, and the purest gem is that which brings satisfaction to the creator and to creation and which expresses the real (haqiqa) and the unreal (majaz), as has been said [by Nezami Ganjevi]:

Speech came from the azure dome.

From the skies, speech descended.

If there were a better gem than speech,

then it would descend instead of speech.

Therefore, there is no monument superior to poetic composition or prosaic arrangement, which

when read someday by someone in love,

will quench the fire of pain with its freshness.

The reasonable take advice from it.

Their wise hearts are comforted by it.

Therefore, I, Jahan, daughter of King Masʿud, ravaged by the hands of time, contented myself with piety, turned my heart toward the Kaʿba of redemption, and acted according to this verse [by the 12th century poet Khaqani]:

Choose to be alone and don’t seek company of friends.

Live alone and don’t ask for intimacy from your acquaintances.

Everything that happened brought something to my mind. For myown sake, every now and then I composed a piece as frenzied as lovers, as distressed as the impatient, as broken as the heart of the clear-sighted, in vain like the passion of the infatuated, in the grip of the boredom of days and nights, in order to busy my mind: I covered truth in the guise of tropes, and quenched my sorrows with the tears of self-expression. However, some low-spirited people are arrested by the appearance of my writing. As untalented they are, they cannot unveil the meaning of my words and blame my wonderful work.

Not every eye is capable of looking into the sun.

Not all drops can join the sea.

To the meticulous experts and high-ranking scrutinizers, that apparent state and that uttered speech are suggestive and revealing. Speech aims not for manifest meanings but for the secrets of being in general. Detailed tropes lead to genuine states of mind. As it is said, “tropes are a bridge to truth.” It is clear to the masters of knowledge, reason and morals that if poetry were not a chosen virtue and a gift of the chosen, the greatest companions of the Prophet and the renowned scholars—may God be happy with them all––would not trouble themselves to acquire it and would not endeavour to excel in it.

However, because Iranian noblewomen and ladies have been rarely occupied with poetry so far, I submitted to the common belief that there is a certain fault with women and avoided it seriously. But it was known by repeated and successive examples that great noblewomen and distinguished ladies, among both Arabs and Iranians, have earned renown in this art. If poetry had been forbidden, the Prophet’s dear daughter, the sun-signed moon, the pearl of the casket of chastity, the Lady of Hereafter, Fatemeh Zahra––may God be happy with her––would not have recited poems. As this [Arabic] verse, attributed to her majesty, says:

Women are fragrant flowers created for you

and all of you crave to smell flowers.

All Arab noblewomen have made poems, and in Iran, Aisha Mughriya who is unanimously one of the seekers of the path of faith and one of the birds of the way of certainty, has earned renown from her poetry. These two quatrains are hers:

If I enjoy your union, it’s sweet.

If I deserve your arrow, it’s sweet.

It’s impossible that I will be with you.

If I’m in your memory, it’s sweet.

All my life I have borne the sorrow of your absence.

I have made love with you away from you.

I have not talked about it with you,

as I don’t see myself worthy of you.

And other Iranian noblewomen like Padshah Khatun and Qotloghshah Khatun and others have ridden the steed of their talent in this field in whatever way they could. I imitated them and dared to compose poetry too, though it is said:

Not everyone can make verse.

Not everyone can bring poems.

Speech comes from virtue.

Speech does not come without knowledge.

I hope for the immense generosity and great kindness of all people of knowledge and letters, and all masters of reason and manners, that they may point out the faults in my talent and my limited capacity and scrutinize my work without ill intention and without prejudice. If they find anything good or bad, adequate or inadequate, in these words, they will gently make corrections and not blame me for my errors.

Excuse the mistakes, if any.

Masters do not blame disciples.

The above poems are taken from:

Jahān Malek Khātun, Divān-e kāmel, ed. Purandokht Kashani Rad and Kamel Ahmad Nejad (Tehran: Zavvar, 1995).

Javad Bashari, “Newly-found poems by Jahan Malek Khatun,” Payam-e Baharestan 1 (3): 740-766.

TRANSLATORS’ NOTE

Although Jahan Malek Khatun has not received the same attention as her contemporary Hafez, who was also from Shiraz, her ghazals, which mix witty sarcasm with provocative reflections on female desire, merit attention on their own terms. Jahan’s poetry was not published in Iran until 1995, when Purandokht Kashani Rad and Kamel Ahmad Nejad published the first edition of her work. More recently, Javad Bashari has added several newly found poems to her known output. Renowned Persian-English translator Dick Davis has translated a number of her poems in Faces of Love: Hafez and the Poets of Shiraz (2012) and The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women (2019), but many more remain untranslated.

This selection includes three ghazals by Jahan, as well as her prose preface to her collected poems, which is translated here for the first time into English. The latter is the only known preface by a premodern Persian female poet, and it revealingly locates her writing within a long tradition of female poets in Persian and Arabic. As an early manifesto of women’s writing, it offers insight into the position of the woman poet within medieval Persian culture.

The challenges of translating Jahan’s poems are similar to the challenges of translating any ghazal. How to capture the magic of the radif (refrain) in a foreign tongue? How to reproduce the lyric power of her voice without descending into mere repetition? We have aimed, as always in our translational practice, to keep faith with the poeticity of the original rather than with any precise word or syntactic order.

Jahan Malek Khatun (fl. 1324-1382) was an Iranian poet and princess at the Injuid court, which had its capital in Shiraz. She was a contemporary of Hafez, and is the only known premodern Persian poet to locate her writing within a tradition of female poets in a prose preface to her collected poems. She is best known for her ghazals.

Rebecca Ruth Gould is the author of the poetry collection Beautiful English (forthcoming in 2021) and the award-winning monograph Writers & Rebels (2016). She has translated many books from Persian and Georgian, including, with Kayvan Tahmasebian, High Tide of the Eyes: Poems of Bijan Elahi (2019). A two-time Pushcart Prize nominee, she was awarded the Creative Writing New Zealand Flash Fiction Competition prize in 2019.

Kayvan Tahmasebian is a poet, translator, literary critic, and the author of Isfahan’s Mold (2016) and Lecture on Fear and Other Poems (2019). His poetry has appeared in Notre Dame Review, the Hawai’i Review, Salt Hill, and Lunch Ticket, where it was a finalist for The Gabo Prize for Literature in Translation & Multilingual Texts in 2017. With Rebecca Ruth Gould, he is co-translator of High Tide of the Eyes: Poems by Bijan Elahi (The Operating System, 2019).