Her Boldest Self

Last month, I visited my eighty-six year old mother, Geraldine, in New Jersey where she lives in a building for seniors. On the third morning, I woke to find that she had been up all night struggling to breathe. To my exasperation, she had waited out the terrifying night sitting up in a reclining chair alone because she did not want to disturb my sleep. I called an ambulance.

Last month, I visited my eighty-six year old mother, Geraldine, in New Jersey where she lives in a building for seniors. On the third morning, I woke to find that she had been up all night struggling to breathe. To my exasperation, she had waited out the terrifying night sitting up in a reclining chair alone because she did not want to disturb my sleep. I called an ambulance.

In the ER we learned that my mother had congestive heart failure—three leaky heart valves had caused a flood in her thoracic cavity and left her gasping for oxygen. The doctors told me that over the next weeks she would be assessed to see if she was strong enough to have a heart surgery that would save her life.

My mother could not move, could hardly talk, and needed to be on a BiPAP breathing machine which forced air into her lungs for long bouts. The BiPAP required that she remove her dentures and when she did, her mouth caved in. She looked one-hundred years old. We swept her thin hair back over her head to reveal that her hairline had receded to the crown. Some days she could only write on a board because she had no breath to talk. It was in this state, at her most vulnerable, not knowing how much time was left, when I saw a change come over my mother.

* * *

Geraldine grew up in the Bronx during the depression with her alcoholic mother and three younger siblings. As the oldest child of four in a single parent household, it was her job to keep the world out and to hide the mess—the bare refrigerator, the empty wine bottles, her mother’s weeks-long benders—from the world.

“Never answer the door,” her mother would tell her. “They will take you all away.”

Geraldine survived her mother, but always kept herself a little apart from the world, even long after her mother died.

* * *

My mother was a lion in so many ways. After the Bronx, she moved to Brooklyn, married, worked as a drill inspector in the war, cared for my father through Lou Gehrig’s disease, got a job back out in the world after twenty-five years of working at home, and helped all of her six kids through college (the first generation to do so). Despite all that, she was timid about connecting to people in the larger world. Her best friend was her sister, and she didn’t put herself out there to get to know peers, co-workers, or neighbors as friends. Our teachers and doctors were professionals that she viewed with deference and from whom she kept a distance. I believe some part of her always felt less-than and remained the ashamed, scared kid behind that door in a crappy apartment in the Bronx with a mother who was a boozer.

So it is no surprise that in my mother’s building for seniors, she has kept the other women at arm’s length. Though she’s lived there for fifteen years, she doesn’t invite women in for dinner, take them into her confidence, or have a best friend. They like her, and she will go with them to the market on the dial-a-ride, chat during mail call, and have a smoke with a couple of the women in front of the building, but that’s as far as she will let it go.

“I’m a loner,” she tells me.

This is hard for me to accept. She is the person who made me feel at home in the world. I grew up in her kitchen, where she made feasts of roiling pots of spaghetti sauce, with meatballs bobbing below the surface, for our sprawling family of eight. When I was a little kid in the big white tub, she would take time to show me how to blow bubbles from a bar of Ivory soap through a loop in her fingers, her long slow deliberate breaths creating an iridescent bubble on the water’s surface. She was the mother who embraced me as I was—shy, quiet, introverted—letting me hide behind her leg until I was ready to come out to greet the world. How many times had I stayed up all night talking with her when I brought my own kids home to savor her? I know what she has to offer.

In her apartment in the evenings, instead of letting anyone in, she preferred to blast MSNBC, keeping an eye on Trump so she’d know which representative to call to thwart his evil plans.

* * *

When I arrived in her hospital room after her first long night in the ER, my mother sat propped up on three pillows in her bed. Edith, a nurse, stood beside her to administer a breathing treatment. Her eyes looked happy to see me through the puffs of mist around her face. I noticed that my mother had reached her long thin hand into Edith’s. They stayed like that till my mother was done.

A man came with a white shih tzu therapy dog who climbed into my mother’s bed. The man was originally from Brooklyn, like my mother, and she talked to him for an hour about her old neighborhood, listening to his stories while she patted his dog sleeping beside her.

The nurses found reasons to come into my mother’s room to watch the news with her, share pictures of their kids at prom, or tell her stories. Edith came from El Salvador and was raising a pretty fifteen-year-old daughter alone. Annie’s son had to go to the Emergency Room in the night after an accident when he landed on his face. Lauren hung around long enough in my mother’s room to cheer beside her when Steve Bannon left the White House.

One morning my mother told me she’d called for Annie in the night because she had passed gas and worried that maybe she’d had a bowel movement.

I felt almost mournful for my mother when she told me this. She took pride in her appearance, always dressing for the day with lipstick, clean clothes, and her bun neatly placed on the top of her head. In the hospital, she had to use a commode, but I imagined this accident would humiliate her.

She told me what Annie had said while she was cleaning her: “Oh yeah. That’s more than gas. This thing is so big you could name it.”

She told me what Annie had said while she was cleaning her: “Oh yeah. That’s more than gas. This thing is so big you could name it.”

Instead of being embarrassed, my mother offered up a name, “Brownie.”

Annie and my mother laughed so hard they had to put the BiPAP machine back on my mother. Who was this woman chillaxing with the nurses?

After a procedure one day, I soothed my mother by putting a cold washcloth over her head while she was intubated. I asked Sue the nurse to please hurry with anesthetic so my mother could go back to sleep because the tube was so uncomfortable. Sue squeezed through doctors doing tests and rushed in to give my mother the anesthetic.

“You’ll be sleeping soon,” Sue assured her.

As the panic receded, my mother had something she urgently needed to communicate. She kept putting her hand to the side of her breathing mask. Finally, I gave her a pen and paper. “Kisses to Sue for helping me,” she wrote.

When there is an eclipse, it is my mother’s room where nurses, doctors, and respiratory therapists stream through to look at the rare celestial celebration in the sky.

The surgeon, Dr. McGovern, comes to talk to my mother about the possibility of going forward with the surgery. He is six-foot-five and seems imposing over my mother who lies in the bed, barely making a dent. In the past, this person would have intimidated my mother.

“Most hospitals would not do the procedure on someone as frail as you. The recovery will be tough. You will have to learn to walk again. Would you work hard to walk again?” he asks her.

She doesn’t miss a beat. “Damn right,” she says, holding his gaze.

He does a double take.

An hour later, after conferring with the team, they decide to go forward with surgery. Her determination and bravado win her a chance at life.

* * *

Although my mother is pretty, she is famous in our family for looking uncomfortable in photographs. Her eyes are usually closed, her mouth is a self-conscious, tight smile, and her posture is tense. Here in the hospital, in every photo, she is relaxed and radiating love.

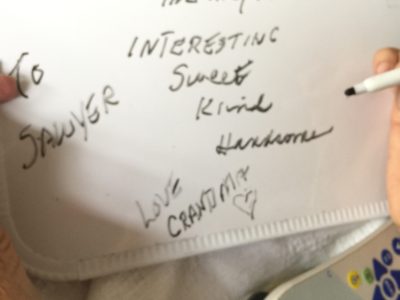

Each day she writes words of love to us and our children on her white board. “Sawyer—interesting, sweet, kind, handsome.”

Each evening she kicks us, her daughters, out. “Go have dinner, be together. Be with each other.”

The next day we show her selfies from dinner, hugging each other, hanging out.

“Makes me happy,” she writes on her board.

The day before her operation, she sends me to get thank you cards for three nurses. She can hardly talk from all the fluid in her lungs. Her sentences are key words strung together.

The day before her operation, she sends me to get thank you cards for three nurses. She can hardly talk from all the fluid in her lungs. Her sentences are key words strung together.

I buy the cards and I imagine that I will write them out for her. But when I get back in the room, she is determined to write them herself. I hand each card off to her.

To Annie: “Big loving arms, kind heart, thoughtful.” To Myrna she writes, “Huge wide smile, comforting words, soft hands.” And to Edith, “Kind presence, loving hands, makes me laugh.”

She has a few words left, and this is how she will spend them. In her darkest moment, I feel her standing out from behind the door, at the center of her life, comfortable in the world. Finally, she shares the person I know—funny, wise, strong, loving—with the world outside that door.

I don’t know what will happen with my mother, whether the surgery will be successful or if she will regain her quality of life. But in these days, when time is running out, she forgot to stay hidden. The world is getting to enjoy the light that is her and she is getting to know that the world wants what she’s got. In these days, she has taught me that it is never too late to open the door, reach for a hand, and step through.

Kathleen Katims is a candidate for an MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University. She writes fiction and creative nonfiction. Her work has been published in Verdad Magazine, Switchback, and The Penman Review. She is working on a book called Second Acts, interviewing, researching, and writing about people who had interesting journeys out of being stuck and moved in the direction of their dreams. She lives in Los Angeles, California with her awesome husband, two cool cat kids, and big brown dog.

Kathleen Katims is a candidate for an MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University. She writes fiction and creative nonfiction. Her work has been published in Verdad Magazine, Switchback, and The Penman Review. She is working on a book called Second Acts, interviewing, researching, and writing about people who had interesting journeys out of being stuck and moved in the direction of their dreams. She lives in Los Angeles, California with her awesome husband, two cool cat kids, and big brown dog.