In and Out

I learned to breathe in Virginia Beach, at the age of thirty-six. We arrived there in April of 1999―the cusp of a new century. Our little family of four: my husband, Bob, and our two young daughters, Kiran and Priya. Three thousand miles of water became the bulwark against our previous lives in London, England.

I learned to breathe in Virginia Beach, at the age of thirty-six. We arrived there in April of 1999―the cusp of a new century. Our little family of four: my husband, Bob, and our two young daughters, Kiran and Priya. Three thousand miles of water became the bulwark against our previous lives in London, England.

Bob’s new position was with the same employer, but his commute was now twenty minutes to Norfolk, Virginia, home of the world’s largest naval station. We were often asked, “Are you military?” We weren’t. And also: “Which church do you go to?” We didn’t.

After twelve years of marriage, Virginia Beach offered us the freedom to become a family of only four, far away from the interference of peripheral members― the root cause of our frequent, heated arguments. I had to decide if I wanted another child. And consider the repercussions of giving birth to another not-boy baby. I didn’t know how important it was to Bob that he have a son; it seemed to be the only thing that mattered to his mum. Stuck in the borderland between his mum and me, Bob had found an escape route, across the Atlantic.

Priya was a beautiful bundle at three-and-half years old: shiny long curls; symmetrical face; a loud, smart, free spirit; irresistible. She turned heads wherever she went. Nine-year-old Kiran had had to leave her diverse clutch of school friends behind; the bonds that had been developing since their first day together at the attached public preschool, around six years prior. They were bold, confident, imaginative, and always had such fun together. Kiran didn’t complain, though the move was probably hardest on her.

In the summers we rode the Elizabeth River Ferry between Downtown Norfolk and Old Towne Portsmouth, warm breezes caressing our faces, water droplets baptizing. The girls giggled with incredulous delight at the huge bubbles they could create at the Children’s Museum, bubbles that rose up in a cylinder around them as they pulled on a rope. We spent hours at the beach, where the ocean sighed as the girls played in the sand, the city-employed entertainers amused residents and tourists alike, then the fireworks crackled and twinkled and exploded, releasing color into the darkness.

Bob and I visited the Chrysler Museum of Art while the girls were at school. In equal measure, both the exhibits of M. C. Escher’s impossible constructions and the enormous slices of cake served on dinner plates in the café helped me to fall in love with America.

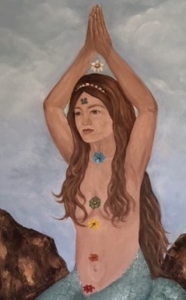

Para and Maitreyi, two ostensibly white, devout, American yogis, in their mid to late twenties, taught me how to breathe. They had traveled to India―the country of my birth―in search of something they had not been able to find in America. Upon their return home, they established Community Yoga―a donation-based yoga studio that would not turn people away because of a lack of finances.

At Community Yoga I was invited to just be. To breathe. Not the shallow type of breathing that was the only possibility when constantly working to hold my belly in, but the kind that requires an expansion of the belly, that rises slowly upwards, lungs filling, to rest in the throat area, where the chakra― or energy center―associated with communication is located. It is at the resting point that the tension begins to dissolve for me. Then the wind of exhalation reverses course, belly contracting to help expel the breeze outwards. In and out. Something we do without thinking, yet when performed consciously, can usher in a serenity that was quietly waiting to be invited in.

I discovered Community Yoga while searching for an alternative to kick boxing, which had resulted in a knee injury. The spiritual side of yoga was an unexpected gift. The studio was newly founded so classes were often small. Although it wasn’t good for business, I was pleased when I was the only student, because I received one-on-one teaching. I learned quickly under their devoted, expert guidance, with their soothing, meditative music in the background, and the warm, playful flickering of the candles. I began to spend more and more time there, helping out with cleaning and providing items they needed but could not afford.

For the first time in our married lives we could manage on Bob’s salary alone. I didn’t want to return to teaching high school mathematics, but I was unable to consider any alternative employment without a work permit. So I enrolled at Old Dominion University. Feminist Thought gave me the language to think about my subordinate position as a woman in my culture, and more widely in Western society. Among the books I read in the Women Writers class was Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, George Elliot’s The Mill on the Floss, Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, and Claire De Duras’s Ourika (translated by John Fowles). I identified with Elliot’s protagonist, Maggie, who was suffocated by the rules she was supposed to live by. As I read Ourika, the uncontrollable deluge of tears I released surprised me. It’s based on the true story of a rescued Senegalese slave girl, raised by an aristocratic French family during the French Revolution; she exists in the liminal space between two cultures, belonging to neither. The tides of time had brought the waves of words written by women so long ago, to wash over me, and connected me to myself and to them.

I learned about Reiki, a healing modality based on energy centers within the body while in conversation with one of my mathematics professors in London. She was someone I had a great deal of respect for, so I knew that if she held it in high regard, it was something I could trust. When I found a Reiki teacher I studied with her until I achieved master level proficiency. In combination with the deep breathing I had learned, I began to ask the healing energy of the universe to heal me and others in my life. Reiki sessions always left me with a profound sense of peace, even when I was working on other people. I felt a connection to something that was both a part of me and much greater than me. I’ve been asking the healing energy of the universe for guidance ever since.

Virginia Beach turned out to be a stepping-stone for us. The company Bob worked for was bought out by another, so three years after we first uprooted, we moved again―this time to California. Six thousand miles between us and our families of origin. I hadn’t found the instruction manual for my life that I’d naively always wanted, but in Virginia Beach I learned how to create an inner calm, that allowed for contemplation without the fog of self-doubt, of confusion. Bob and I both decided we didn’t want to have any more children. It felt as though the fissures in our marriage were beginning to close up, that our marriage may survive.

Sarita Sidhu is a nonfiction writer and an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. She has worked as a teacher and an advocate of Fair Trade for many years.

Sarita Sidhu is a nonfiction writer and an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. She has worked as a teacher and an advocate of Fair Trade for many years.