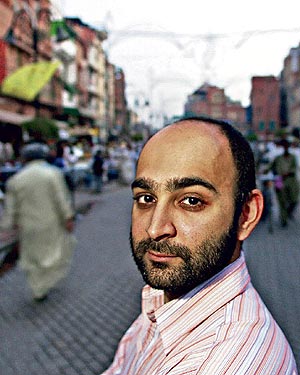

Litdish: Mohsin Hamid, Author

Mohsin Hamid is the author of three novels: Moth Smoke, a finalist for thePEN/Hemingway Award; The Reluctant Fundamentalist, a New York Times bestseller that was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and adapted for film; and, most recently, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia. He is also a columnist for The New York Times Bookends.

Zainab Shah: You write in English in a country where most of the population doesn’t speak it. How has your writing, which has garnered critical acclaim globally, been received in Pakistan?

Mohsin Hamid: Pakistani college students read English writing mainly to access the world. I also find they are currently looking for representations of a contemporary alternative reality that is not talked about or written about much, but does exist; this much was clear to me with Moth Smoke, my first novel, and more recently at Lahores’ first Literature Festival, where hundreds of people turned up for my talk. A most telling moment for me was when I received a letter from a religious young man telling me how much he loved reading Moth Smoke—which is about sex, drugs and crime.

ZS: How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia is a short novel written in second person. Why did you chose this form to tell the story of your unnamed protagonist?

MH: What interested me most while I was writing this novel is a changing aesthetic of compression, or how to express big ambitions in a small space. The story of my unnamed protagonist is an age old one, common in lengthy Bollywood films, I wanted to elevate this Bollywood film trope by way of compression. I also drew inspiration from ghazals which again tend to be quite lengthy and about transcendence and longing for an unknown loved one, something you can find in the unnamed protagonist of How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia. Again I was interested in the representation of those same emotions, but in compressing them without diluting their intensity on the page.

[In writing,] there are no rules. And if you want them to be, make your own. Pick your own constraints. Catalyze the imagination of a reader by putting the minimum out there. Leave space for a reader to do their thing and use their imagination.

ZS: Do you have a process? And if so, what is it?

MH: I do and I don’t. It depends really. I almost always throw away the first couple drafts. I tend to write with my eyes and edit with my ears, always reading aloud what I’ve written. It has to sound like somebody is speaking, the character of that somebody should be clear. In that sense sometimes I feel like being an actor is a big part of being a writer. My plan for this novel was originally to assemble a collage of different voices, at least that’s what I was thinking when I wrote ‘Terminator: Attack of the Drone,’ published in The Guardian in 2011.

ZS: What are your recommendations for writers?

MH: There are no rules. And if you want them to be, make your own. Pick your own constraints. Catalyze the imagination of a reader by putting the minimum out there. Leave space for a reader to do their thing and use their imagination.

ZS: What kind of research do you do before or while writing a novel?

MH: No research. I do rely a lot on my powers of observation and the conversations I have with people around me.

ZS: What are you interested in writing about next?

MH: Women. And women’s points of view.

ZS: Why?

MH: I think the oppression of women in the form of honor killings in Pakistan exists ultimately because people are afraid of the potential power of women, an idea I’d like to explore. Also because now I have a three-year-old daughter, Dina.

Perhaps it’ll be a children’s story for her about being a woman. Every night I tell her a bedtime story but she has such an amazing imagination, she’s actually the one that ends up telling me the story she wants to hear by questioning what I’m telling her. She keeps me on my toes. It’s good exercise for any storyteller.

ZS: Is it safe to say that’s what your next novel will be about?

MH: I don’t know. I hate talking about it. There’s something precious in having a secret, and the desperation to share the secret keeps you writing like a long-distance relationship keeps you yearning.

ZS: One book you wish you wrote?

MH: None really… actually, maybe Charlotte’s Web, since it casts death as a natural, cyclical process—it’s sad, but not frightening.

ZS: What’s your unwinding process like?

MH: Can’t say in an interview (with a chuckle). I had a misspent youth, and continue to misspend my leisure time.

ZS: Parting words?

MH: Life is very significantly chance. Love is the only real valuable technique to deal with life and chance.

ZS: Favorite dinosaur?

MH: Pterodactyl.

_____________

From How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia:

Look, unless you’re writing one, a self-help book is an oxymoron. You read a self-help book so someone who isn’t yourself can help you, that someone being the author. This is true of the whole self-help genre. It’s true of how-to books, for example. And it’s true of personal improvement books too. Some might even say it’s true of religion books. But some others might say that those who say that should be pinned to the ground and bled dry with the slow slice of a blade across their throats. So it’s wisest simply to note a divergence of views on that subcategory and move swiftly on.

None of the foregoing means self-help books are useless. On the contrary, they can be useful indeed. But it does mean that the idea of self in the land of self-help is a slippery one. And slippery can be good. Slippery can be pleasurable. Slippery can provide access to what would chafe if entered dry.

This book is a self-help book. Its objective, as it says on the cover, is to show you how to get filthy rich in rising Asia. And to do that it has to find you, huddled, shivering, on the packed earth under your mother’s cot one cold, dewy morning. Your anguish is the anguish of a boy whose chocolate has been thrown away, whose remote controls are out of batteries, whose scooter is busted, whose new sneakers have been stolen. This is all the more remarkable since you’ve never in your life seen any of these things.

The whites of your eyes are yellow, a consequence of spiking bilirubin levels in your blood. The virus afflicting you is called hepatitis E. Its typical mode of transmission is fecal-oral. Yum. It kills only about one in fifty, so you’re likely to recover. But right now you feel like you’re going to die.

Your mother has encountered this condition many times, or conditions like it anyway. So maybe she doesn’t think you’re going to die. Then again, maybe she does. Maybe she fears it. Everyone is going to die, and when a mother like yours sees in a third-born child like you the pain that makes you whimper under her cot the way you do, maybe she feels your death push forward a few decades, take off its dark, dusty headscarf, and settle with open-haired familiarity and a lascivious smile into this, the single mud-walled room she shares with all of her surviving offspring.

What she says is, “Don’t leave us here.”

Zainab Shah is a Pakistani writer completing her MFA at Antioch. She lives in New York and can most often be found in parks.

Support indie bookstores and find a copy of How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia near you with IndieBound, or order it through The Independent Online Booksellers Association!

Click here to buy Hamid’s How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia on Amazon!