Invitation / Memories

[translated poetry]

Invitation

Ida

Pierced the light

The air thick as fog

The black mirror full of moss

Is shatter-scattered now

In an empty airy room

Let’s be happy again

Back to seventeen

Cycling coupled together

We go down this road

Be happy

Don’t care about anything

Sweet delight

Let the rains come

We bathe ourselves sopping

Knowing for sure we’ll soon be dry again.

Ajakan

Ida

Menembus sudah caya

Udara tebal kabut

Kaca hitam lumut

Pecah pencar sekarang

Di ruang lepah lapang

Mari ria lagi

Tujuh belas tahun kembali

Bersepeda sama gandengan

Kita jalani ini jalan

Ria bahgia

Tak acuh apa-apa

Gembira-girang

Biar hujan datang

Kita mandi-basahkan diri

Tahu pasti sebentar kering lagi.

Februari 1943

Memories

to Karinah Moordjono

Sometimes

Between these familiar bars

They yield colours

Worn out things are forgotten

Ah! You feel yourself scatter

Soaring high above the present

A brief moment

Only. Finely fragile these interwoven memories

Break vanish before being held

Shocked

Back to the mundane

The soul asks: Must the fruit

of life fall so often to the ground?

Covered in choked regrets over the ever-wasted

Kenangan

untuk Karinah Moordjono

Kadang

Di antara jeriji itu-itu saja

Mereksmi memberi warna

Benda usang dilupa

Ah! tercebar rasanya diri

Membubung tinggi atas kini

Sejenak

Saja. Halus rapuh ini jalinan kenang

Hancur hilang belum dipegang

Terhentak

Kembali di itu-itu saja

Jiwa bertanya: Dari buah

Hidup kan banyakan jatuh ke tanah?

Menyelubung nyesak penyesalan pernah menyia-nyia

19 April 1943

TRANSLATORS’ NOTE

Chairil Anwar “Invitation” and “Memories” Translator’s Statement

Indonesian (or “Bahasa Indonesia,” literally “Indonesian language”) is the current official language of Indonesia. It started its life as a trade jargon, and until the early 1900’s few Indonesian writers used it for literary purposes, preferring instead the local languages like Javanese or Balinese. However, as a movement for pan-Indonesian national independence grew in the 1930’s and 1940’s, Indonesian seemed a fitting vehicle for communication across the large archipelago. Chairil Anwar is one of the first poets to work in modern Indonesian—a pathbreaker who helped show people the way.

Indonesian’s origin as a trade language has huge consequences for its use in poetry. Like most trade languages, it is very simple, creating a low barrier for new learners. There are no tenses and no singular vs plural divide, and any two nouns can be placed next to each other to create a sentence. The two words, “kucing samudra” can be interpreted as “The cat of the ocean,” “The cat is an ocean,” “The cat that belongs to the ocean,” “The cat, the ocean,” “The cat and the ocean,” and more.

In the two poems above, “Ajakan” (“Invitation”) and “Kenangan” (“Memories”), we have opted to interpret Anwar in a more jagged, fragmented way than we might have. For instance, for “Kenangan,” a previous translator (Burton Raffel) put the opening four lines this way:

Sometimes

On these same old bars

Something withered and forgotten

Bursts in full color. (The Complete Poetry and Prose of Chairil Anwar, 37)

Although this reads as closer to ordinary English, we felt that it ironed out some of the deep peculiarity of the original poem (such as the ambiguous “they”/“mereksmi”). On the other hand, we did opt to read grammatical connections into the poems that we could have left out, such as the “is” in line 5 of “Ajakan.” In Indonesian, “is” is rarely used; instead, subject and predicate are simply placed side by side. So it was up to us whether we wanted to make it explicit or leave it up to the reader. In this case we thought an explicit “is” would be a good idea.

These two poems are about experiences of breakage, moments where consciousness moves from one modality to another in a jumble of images and sensations. Anwar makes use of the specific linguistic resources of Indonesian to put the reader on the defensive, forcing us to stop at one line and go read the previous one in the light of the later one, always unsure if we are reading a disjointed phrase or a sentence. We hope we have communicated his particular style while keeping the poem an enjoyable and ultimately intelligible thing.

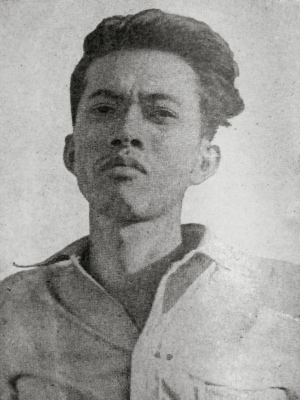

Chairil Anwar (1922-1949) has been called “Indonesia’s greatest literary figure.” Born in Medan, North Sumatra, he moved to Jakarta at the age of 19 where he mixed with the literary circles that would come to be known as the “Generation of ‘45.” From 1942 until his death in 1949 he wrote seventy-odd poems, along with some prose pieces, radio scripts, and translations. The anniversary of his death is celebrated in Indonesia as National Literature Day.

Harper Campbell currently lives in Calgary. He has published poetry in Salish Seas: An Anthology of Text + Image (2011), an essay in The Salt Chuck City Review (volume 1, 2019), translations of the Indonesian poet Chairil Anwar in ezra (forthcoming), and book reviews at the Ormsby Review. He has an honours degree in philosophy and Asian studies from the University of British Columbia.

Christoffer Dharma, born and raised in Jakarta, Indonesia, is a PhD student at the University of Toronto. He has published nearly 20 scientific articles in the field of epidemiology; his current research interests are in social isolation, sexuality, and mental health. Over the years, he has published a few Indonesian-language poems on his experiences growing up in Indonesia as well as some translations of Chairil Anwar in the Columbia Journal (2021).