Jimmy Santiago Baca, Author

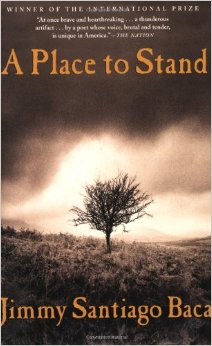

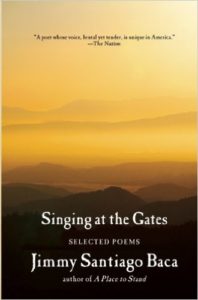

Jimmy Santiago Baca was born in New Mexico of Indio-Mexican descent. He is the author of numerous poetry collections, including Immigrants In Our Own Land, published in 1979, the same year Baca was released from prison. Other poetry titles include Healing Earthquakes (2001), C-Train & 13 Mexicans (2002), Winter Poems Along the Rio Grande (2004), and Spring Poems Along the Rio Grande (2007). In 2015, his retrospective collection Singing At the Gates was published and features over four decades of Baca’s work. He is the winner of the Pushcart Prize, the American Book Award, and the International Hispanic Heritage Award. He was awarded the 2006 Cornelius P. Turner Award for his memoir A Place to Stand, which has inspired a new documentary and educational initiative. Baca has devoted his post-prison life to writing and teaching others.

Jimmy Santiago Baca was born in New Mexico of Indio-Mexican descent. He is the author of numerous poetry collections, including Immigrants In Our Own Land, published in 1979, the same year Baca was released from prison. Other poetry titles include Healing Earthquakes (2001), C-Train & 13 Mexicans (2002), Winter Poems Along the Rio Grande (2004), and Spring Poems Along the Rio Grande (2007). In 2015, his retrospective collection Singing At the Gates was published and features over four decades of Baca’s work. He is the winner of the Pushcart Prize, the American Book Award, and the International Hispanic Heritage Award. He was awarded the 2006 Cornelius P. Turner Award for his memoir A Place to Stand, which has inspired a new documentary and educational initiative. Baca has devoted his post-prison life to writing and teaching others.

* * *

The first time I saw the name Jimmy Santiago Baca was in 1991, on the pink title page of a film script that read: Blood In. Blood Out. Screenplay by Jimmy Santiago Baca.

Directed by Academy Award winner Taylor Hackford (aka Helen Mirren’s husband), much of the film was shot on location in San Quentin. It was scheduled for release in the spring of ’92—that is, until the Los Angeles riots broke out. A scared studio, uncomfortable with gang and Mexican mafia themes, renamed it Bound By Honor and watched it tank at the box office. But Baca’s powerful work, based on his own life experiences, rose to unexpected heights. It went viral long before there was social media, sinking deep into the cultural consciousness of the Chicano community, while resonating with diverse audiences across the country and the globe. It enjoys cult classic status to this day.

In 2013, it was another film project that led me to discover Jimmy Santiago Baca, the poet. Daniel Glick, a young filmmaker was producing a documentary version of Baca’s award-winning memoir, A Place to Stand. A trailer for the film begins with prison images and supers that read: In 1973, Jimmy Santiago Baca was sentenced to Arizona State Prison. He was sentenced to a life without meaning or hope. Until he created his own.

Baca was 21 when he entered prison, sentenced to over five years on drug related charges. Abandoned by his parents, he had already spent much of his life living on the street, and was functionally illiterate. Against all odds, and in defiance of a prison board that rejected his request for education, Baca taught himself to read and write. He sent poems to respected literary journals, got them published, and began a dialogue with the world from his cell. His first chapbook was released before he was.

Baca was 21 when he entered prison, sentenced to over five years on drug related charges. Abandoned by his parents, he had already spent much of his life living on the street, and was functionally illiterate. Against all odds, and in defiance of a prison board that rejected his request for education, Baca taught himself to read and write. He sent poems to respected literary journals, got them published, and began a dialogue with the world from his cell. His first chapbook was released before he was.

A few years ago, inspired by Baca’s memoir and poetry, I arranged for a conversation* between Baca and my husband, Carlos Carrasco, the actor who played Blood In Blood Out’s quintessential bad guy, Popeye. Carlos asked Jimmy to recount his journey into writing. The specific question was: “How did you do it?” It wasn’t the first time Baca had been asked this question, and it wouldn’t be the last.

As I prepared for this Lunch Ticket interview, I thought about asking, “How did you do it?” yet again, but Baca’s original response, transcribed below, captures it all:

Jimmy Santiago Baca: Generally speaking, when someone speaks about how did you come into this craft?—they’re speaking institutional or systematic approaches. ‘Well my mom took me to my first poetry reading,’ or ‘my father got me signed up at Sarah Lawrence College for poetry classes’ or ‘my girlfriend gave me this book.’ Americans in a great many ways are spoiled. So if you ask a man who cannot read or write in a prison cell in Chile and you give him some charcoal and he doesn’t know how to write and he knows that he will die tomorrow—he’s under the duress of dying tomorrow—he will phonetically make out his sounds on the wall: Love. I Love you my daughter—However that might be spelled on the wall … it will be done. And people will say:

—How did you learn how to do that? I mean you only had a day?

—Well, I was going to die tomorrow and I had to send out a note to somebody that I loved them.

Like black people have soul or Europeans have the muse, Spanish people have duende—it’s that place that transforms you from a body being into a spiritual being.

In other words, the time frame is not adjudicated by pampering. It’s adjudicated by this will be my last time to speak. So how did I learn grammar in the space of three months from not knowing anything about English?—Except functional words like: Stop. Go. Food. Love. Hate. I couldn’t really understand putting together a sentence. How did I get that? I got it because of necessity. I was involved in situations where I was going to kill somebody and somebody was going to kill me. I don’t know how I got myself caught up in that. The second I stepped in the prison somebody tried to stab me I stabbed back. Next thing I know, there’s a death warrant for me and I wanted to tell my grandmother I love you but I don’t know how to write:

—I will learn how to tell you I love you by tomorrow noon. I will learn how to do this.

And I took the book and I took the dictionary and I looked at it and there was nothing between me and that—there was no world, there was no house, there was no payment—there was only [the dictionary and the book} and me. And combined [that] created a third principle of god and with that kind of triangle—any thing is possible. Anything. Anything. This idea that “how did you do it?” is basically saying that we are so pampered that it takes us four years to learn that. How did you do it? That is such a pampered question.

* * *

This past February, I caught up with Baca by phone and, over the course of a few days, he took time from his writing and other responsibilities to answer questions about his past and provide perspective on all of our futures.

Rochelle Newman-Carrasco: You learned to read and write in prison and that’s also where you found poetry. What do you consider your earliest influences? When do you first remember hearing poetry?

I was four years old and there was a certain balance to the water, to the weather, to the seasons, there was a certain balance to everything that gave me a sort of lyrical harmony … that was poetry. There was a sense that there was a divine balance in things.

JSB: The first reference I can remember, I guess I have to go all the way back to nature because, in nature, I responded immediately to the harmony. I instinctively understood that everything was in balance. I was living with my grandmother when I was four years old and there was a certain balance to the water, to the weather, to the seasons, there was a certain balance to everything that gave me a sort of lyrical harmony … that was poetry. There was a sense that there was a divine balance in things. I kind of knew that and participated in it, very, very early. I was blown away—by the waters, by the snows, and the wind. The wind had a certain charm to it. It had a certain voice and I would listen to the wind almost every single day on the prairie. It had a beautiful voice that spoke to me. If you contrast that to the sounds that came from my extended family—my aunts and uncles and such. Their sounds, of course, were—if they were drinking and fighting and stuff—their sounds were violent sounds. And I was very aware of those sounds. I was very aware of the sounds of sorrow. I was aware of the sounds of misery.

Then, of course, there was my grandmother. I would go to church with my grandmother when I was four and there was this beautiful sound of the bell in Mass, the sound of all these old people praying together in unison. […] The sounds in church mixed with the sounds in nature without forcing one upon the other, they sort of blended and merged into this chorus of divine welcome. I felt extremely welcome in those sounds when I was a child. Then there were also the sounds of silence. The sounds of silence were overwhelming. We spent long days that extended into weeks and extended into months and I became extremely familiar and intimate with silence. And silence had a sweet voice to it—it accommodated the leaves on trees, it accommodated the dust, it accommodated the dogs barking. Silence was this extraordinary piece of paper on which the world wrote its songs.

Then of course I went from there to the orphanage, and the orphanage had an orchestra of sounds that also blended into the sort of music that got me intoxicated. We had the choir that I sang in. We had the beautiful music of cows out in the fields. […] Everything seemed to have music to it when I was young….

RNC: Did you access that music in prison – was it stored in you?

RNC: Did you access that music in prison – was it stored in you?

JSB: Oh yeah—definitely the memories recalibrated themselves to become resources for me while I was in confinement. I knew love and I knew what friendship was and I knew what health was, through the ways that silence offered its music to me. I knew the world through its music, and its music was not fabricated in studios where musicians cut their albums, but more—it was the music of everyday common life. It was the music of animals and the music of nature—and I very much heard it and I metabolized it and it became part of my bodily organs. The music became a cellular package that I carried with me in my body as I grew.

RNC: You started reading poets like Byron and Coolidge in prison. In your memoir, A Place to Stand, you wrote about stealing your first book from someone, almost out of spite.

JSB: [The poetry books] belonged to the desk clerk. She was going to college. That was one of her classes. Once I got a grasp of grammar, I went searching for books. There were books laying everywhere, all over inside these prison cells in county jails. I got books wherever I could find them.

RNC: I won’t ask you how you did it, but I do want to understand what you think drives a person like you, maybe someone in prison today. Is the drive to read and write a primal urge?

JSB: You have to have a reason. People who become eloquent—there’s a drive behind their eloquence, there’s a reason behind it. And a lot of kids grow up to learn language and to learn grammar without having any experience built in them that gives them a reason to express themselves. Almost immediately, once you get out of pre-school, when you’re in 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th [grades] in school, there’s a big emphasis on reading books to kids. That happens, and kids are so interested in [books] because they want to use language to explore their experience. But at some point during your time in school, experience is diminished to mean nothing and soon language becomes an instrument—so that you can use it to get yourself a good job. You can use language to get yourself an A-plus. You can use language so that you can hide your secrets.

Nature taught me how to use language to balance myself.

In its orchestra of sounds there was such harmony and balance I guess I picked that up and I learned how to balance my sorrows with my joy. I learned how to balance my fear with my fearlessness. I learned how to balance my solitude with my silence. Language became an incredible tool for me to deal with balancing my world in a very, very imbalanced society.

You can use language so that you don’t express yourself—and people begin to use language for all the wrong reasons. They use language so they can close down their personal experience and [close down] expressing their dreams and their sorrows and their hurts and their disappointments. They begin to use language to cover up and conceal all those emotions—so it becomes aborted—so language doesn’t really have a drive in it anymore. Just like a tool, like a wrench or a screwdriver. When you use it, you’re using it for a purpose. […] Language is used to delineate logical occurrences during your day, but it’s no longer sacred. It’s no longer used to express your divine sentiments, your talking with God, your feelings that are embedded deep in your bones, that are going to help you spiritually find a place in the world that gives you balance. I think the language of nature came to me very early on and people keep asking me how did you do it? How did you do it? And I guess my response to that was that nature taught me how to use language to balance myself. In its orchestra of sounds there was such harmony and balance I guess I picked that up and I learned how to balance my sorrows with my joy. I learned how to balance my fear with my fearlessness. I learned how to balance my solitude with my silence. Language became an incredible tool for me to deal with balancing my world in a very, very imbalanced society.

RNC: You’re a world traveler. Is there a difference between the way poetry, or the poet, is valued in the U.S. versus in other countries?

JSB: It’s really simple. In America we value possessions. In other parts of the world they value experience. And experience translates into stories. People all over the world still value their stories. In America we value possessions. We would much rather talk about a new car than talk about a story that happened between grandfather and me. We’d much rather get on the computer and play video games and enact some cataclysmic epic than to talk about the epics in our own lives. People cling to their old traditions in other countries. They place a lot more value on their stories than we do in this country. […] Reading poetry in other countries is part of every day life. Reading poetry in America is only at the university level and in the classroom. It’s not part of life. It’s part of the lesson plan. Students really excel when they take poetry out of the classroom and apply it to their lives—they really excel when they have answers taken from poetry books to their problems. They become richer people, much richer and they’re a lot nicer to be around, you just want to be around them when you have somebody that can solve some dilemma that you’re experiencing by referring to a poem—poetry has a way of speaking to you that’s directly connected to your deepest recesses in your heart and in your memory, and those are very valuable places that we inhabit specifically to make us human beings. So the question to really ask is: When will you become a human being again? How long will it take you after school to become a human being? When did you leave your human beingness behind? What grade did you stop becoming a human being?

JSB: It’s really simple. In America we value possessions. In other parts of the world they value experience. And experience translates into stories. People all over the world still value their stories. In America we value possessions. We would much rather talk about a new car than talk about a story that happened between grandfather and me. We’d much rather get on the computer and play video games and enact some cataclysmic epic than to talk about the epics in our own lives. People cling to their old traditions in other countries. They place a lot more value on their stories than we do in this country. […] Reading poetry in other countries is part of every day life. Reading poetry in America is only at the university level and in the classroom. It’s not part of life. It’s part of the lesson plan. Students really excel when they take poetry out of the classroom and apply it to their lives—they really excel when they have answers taken from poetry books to their problems. They become richer people, much richer and they’re a lot nicer to be around, you just want to be around them when you have somebody that can solve some dilemma that you’re experiencing by referring to a poem—poetry has a way of speaking to you that’s directly connected to your deepest recesses in your heart and in your memory, and those are very valuable places that we inhabit specifically to make us human beings. So the question to really ask is: When will you become a human being again? How long will it take you after school to become a human being? When did you leave your human beingness behind? What grade did you stop becoming a human being?

RNC: What about Latino poets? Does culture impact craft?

JSB: Chicano people in particular have a gift called “corazon”—they have this thing called corazon and it’s extremely hard to define. It’s like it would be kind of difficult to define “black soul”—like black people have soul or Europeans have the muse, Spanish people have duende—it’s that place that transforms you from a body being into a spiritual being. I think that Chicano people are more apt and readily prepared to understand and experience poetry. I think they’re more willing to cross that line of fear because fear comes to different people in different ways. There are as many fears, types of fears, textures of fears, as there are snowflakes. And I think that Chicano people in particular have never given away their corazon. They’ve never given away that beautiful lesson that they’ve been given. […] All of our experience is imbued with a certain poetic essence and I think we come born prepared to embrace that poetic essence.

RNC: Writers of color engaged in MFA programs and other learning scenarios are often subjected to microagressions and other non-productive styles of communication and feedback from students and teachers. How do you believe this can be addressed?

JSB: Teachers have to be trained. They don’t have enough training in the make up of what America is and they’re taught to fear anything that’s different. Their knowledge is so limited to the book, and most books don’t embrace the experience of people of color. That becomes a real problem, because when a teacher comes in and teaches a group of kids to open their hearts up to their own lives and their own experiences and to learn to express what they have been fearful of expressing before—I mean when you create a classroom, you’re supposed to create a classroom where it becomes a community of people who trust each other, not tease each other, not jeer at each other, not mock each other, not make fun of each other, as is the case today. If some kid in a classroom today gets a failing grade, the rest of the students will look down on that particular student and make fun of that student as being stupid or dumb. When, in fact, that kid has to go home and there’s no food at home, his mother’s shooting up meth, his father’s doing heroin and drinking alcohol. There are some very serious problems and what we are basically teaching the students in class is you just have to stop caring about those kids and move on—and the teacher is the one who fosters that sort of indifference.

What we have to do is get teachers to foster empathy and through empathy we can open experiences that have not heretofore been allowed in the classroom. […] Enlightenment is what we need—young, brave teachers who are enlightened. So many teachers are coming to the classroom so ill prepared it has basically destroyed the educational system—because students don’t want to become robots. They inherently want to take what’s good about them and develop it into something they can contribute to society—and that’s the very thing that ill prepared teachers close down. […]

Enlightenment is what we need — young, brave teachers who are enlightened.

So many teachers are coming to the classroom so ill prepared it has basically destroyed the educational system—because students don’t want to become robots. They inherently want to take what’s good about them and develop it into something they can contribute to society—and that’s the very thing that ill prepared teachers close down.

As it is today, when you have a teacher walk into a classroom, her job, his job is to throw the student out of her own story—eject the student out of their own narrative—and that’s to say: your particular experience does not matter. What matters is that we all pass this test together and we move on to the next grade. But you have to pass the test. So, I’m going to have to throw you out of your story, because your story is insignificant compared to the story I’m about to tell you. The story of your success means you have to get A’s, you have to graduate, you have to go to college, you have to become somebody without ethics or morality and join some business, some institution where your experience still is not needed. So consequently what happens is we grow a population of people who are only really educated in taking orders from their bosses. They’ll do anything they have to do in order to please the boss because it is the same thing as pleasing the teacher. You won’t be betrayed if you do a good job of it. You’ll be praised, and you’ll go to any expense to get that praise. If that means creating a Holocaust situation where guards don’t question their superiors: ‘… are you seriously going to kill these people? And you want me to go ahead and do this?’ And they say yes. That’s exactly the kind of person they cultivated in Germany. The kind of student they cultivated in Germany was one who only took orders and obeyed them. And today, no matter where you look in society, you hear the same replay over and over and over …. No matter where you go that there’s inequity you hear, “I’m only doing my job,” and that’s to say: I’m only doing what my superiors tell me to do—and that’s learned early in the classroom.

RNC: What does success look like for Jimmy Santiago Baca?

JSB: The success I think I have is that my kids are capable of loving, and capable of having great confidence and self esteem, and they’re capable of empathy and compassion—that’s success as a father.

We go to these infinitesimally small altars and we pray before the spark and we hope to carry that spark in the fiercest storms and keep it lit. And that’s really what the poet’s journey is—it’s to keep the spark lit. Carry it like an Olympic torch.

Success as a writer is that I have purposely gone out of my way to shy away from letting these major celebrity machines take over and package me as something to the country that I’m not. What’s happened is that, when I say no to something, most of the people around me say you made a terrible mistake saying no: saying no to being on national TV, saying no to being on National Public Radio, saying no to all these major media outlets that could really send my name out into the world and up book sales by hundreds of thousands. They say you’re not taking advantage of the media and the power that they have. And I say, no. Maybe I made a mistake, but maybe I didn’t. I’m just not going that way. I have faith in people’s word of mouth— they read a book and they tell someone else about it—and as of this date, not one of my books has gone out of print. All 26 books, or however many I have, they all continue to be published,[…] more and more people talk about them, more and more teachers. It’s taken an awful long time for teachers to come around, but it seems like teachers are really getting it now. A Place to Stand is in the top 50 memoirs and biographies—it’s above Whitman, it’s above Angela’s Ashes. It’s one of the best selling memoirs in the U.S. for the last two years now. It inspired an award winning documentary that just got released nationally. But it took time for the teachers to get it. The way the machine runs, it’s their job not only to promote certain writers but also to exclude others. If they want to get someone that’s more palatable to the populist they’ll get someone like Solzhenitsyn,[…] or some imprisoned writer in China and say, look they imprisoned this writer in Russia or in China. […] Accept it to say that we have writers in America that should be read. But they’re not, because we don’t want to admit that we put political writers in prison. It’s a whole other ball game and the publishers are not quite ready to engage.

RNC: Is there a path to poetry, let’s say a path for aspiring poets today?

JSB: The path to poetry has always been the same. You simply wash away all the clutter in your life, just wash it all away and get down [to business]. Poetry is all about the basics of breathing and eating, loving, being trustworthy. It’s all about the same basic things that happened to people two million years ago or whenever. It’s all about the creative spark that has to exist between you and your own God, you and your own mind, and between you and other people. It has to be about your nurturing that creative spark in you and keeping it going and then from there it will take you on your own unique journey.

It’s not about the awards and the accolades and the ten best books of the year. It’s not about exoticizing—everybody wants to make this exotic—Oh, so and so’s in Italy today and Oh, so and so is translating a new book. It has nothing to do with that and it has everything to do with honoring and nurturing the spark that inhabits words. We go to these infinitesimally small altars and we pray before the spark and we hope to carry that spark in the fiercest storms and keep it lit. And that’s really what the poet’s journey is—it’s to keep the spark lit. Carry it like an Olympic torch. Except, you’re not going to carry it to these big events. You’re going to carry it to the smallest, smallest, smallest occurrences in your life—and there it will illuminate some secret truth that’s so necessary for people to enjoy life—and it seems like almost everything that we encounter on a daily basis takes away from that spark.

*For the entire conversation between Jimmy Santiago Baca and Carlos Carrasco, click here.