Judy Bolton, Girl Detective, Girl Thief

I was six years old the first time I saw a mystery novel on my older cousin’s bookshelf with my own name, Judy Bolton, on the spine. I couldn’t stop my finger from tracing the letters boldly printed across the front of that hardcover book. I like to think my father chose the name for me for a reason, and that the appellation Girl Detective inspired me to construct my own clue-imbedded world.

Judy was a fictional detective in the 1930s and ’40s. She spied for the good of her family and community. Four decades later I took a different approach. Mine was a darker brand of sleuthing: I stole and manipulated my way into creating and solving mysteries, in part to get closer to learning about the secrets that lurked in my own house.

I was persistent, though never quite successful. Fictional Judy’s cases had neat endings, while my work was more of a scavenger hunt during which I stole objects that didn’t cohere into a full story for me. I went through my father’s wallet, thick with dry-cleaning slips, receipts and dollar bills. I pretended to smoke his fat, unlit Dutch Masters cigars, and tamped down tobacco in his pipes. When I flash back to Dad’s rack of pipes, silent and stony atop his highboy, I think of the artist Magritte. “This is not a pipe,” the Belgian surrealist wrote below his painting of a pipe. He called the work The Treachery of Images.

There were some deceptive images connected to my father, like the photograph of him in flowing khakis and a pith helmet, labeled Guatemala 1952. There was also the heart-shaped box stitched in red and blue, curiously soft and feminine, that stood out on his dresser. The box was another souvenir from Guatemala in which he kept a silver ring, serious and dense, stamped with his initials KHB, for K. Harold Bolton. I loved to spin that ring around my middle finger. I loved to put it under my pillow at night—a talisman that fueled my own imagined adventures.

My role as the girl detective also masked my role as a thief, a part I began to play in earnest at Edward Morley Elementary School in West Hartford, Connecticut. This was a school heavily populated with pretty Nancy Drews. I planted red herrings in their fifth grade classrooms, full of glitter and glue, to indicate there was a Frito Bandito at large.

I was the clever thief who knew what mattered most to my shiny pony-tailed classmates and gladly took it away from them. I was the phantom thief who struck after yet another birthday party or sleepover from which the Nancy Drews excluded me. In reality, I was short and chubby; I was the Spic ‘n’ Span Baby whose mother with the Cuban accent didn’t allow to walk home alone from school.

I kept some of their sweet little change purses and hand knit scarves and returned the rest, triumphantly, as if I had recovered them. Magritte’s pipe was not a pipe, and I was not a thief. At best, I was an indispensable sleuth; at worst, a slippery suspect in the eyes of my teachers.

When I had stolen all I could in school, I moved on to the most portentous place of all for me as a girl detective: my parents’ bedroom, a place filled with the soundless noise of too much stuff in too small a space. The bedroom was a staging area where I could perfect my thieving skills. I pocketed fake pearl necklaces and matching clip-on earrings from my mother’s vanity—a rickety desk she had transformed with speckled contact paper, gold trim and crepe skirting. It was as fancy as she was when she went out with my father on a Saturday night.

I rummaged through my mother’s closet, even though she made it clear that playing dress up in her best clothes was akin to stealing them. But I couldn’t help raiding her walk-in closet for slender high heels, sequined dresses and my father’s sister’s hand-me-down cashmere sweaters. That closet was an island of eternal twilight and forbidden possibilities. In particular, the very adult possibilities of love and beauty were embodied in a dress my mother bought from the Siegel Shop, a tony store in West Hartford Center. She carefully hung the beautiful fuchsia sheath she intended to wear to my uncle’s wedding in plastic wrapping. The sheath was delicately embroidered with roses and went over a long slip dress in a slightly darker hue. There were pointy, satin shoes dyed to match.

A few days before the wedding I stumbled around my parents’ bedroom trailing fuchsia and turning my ankle in the dyed heels until I came face to face with my father. He stood in the doorway, brown-eyed like me, staring with wonder and dread.

“Don’t let your mother see you in that dress,” he whispered.

It was the same tone he had when he came home from work, his tie undone, his shirtsleeves rolled up. “What kind of mood is your mother in?”

On those occasions we were co-conspirators.

My mother always aspired to have more, to be more. When she was seventeen, she wanted to be the first in her family to attend college. She struggled with an alcoholic father and depressed mother as she waged a fierce battle that left her slapped and bruised. But she saved enough money for bus fare and a Coca Cola to get to the University of Havana. On the first day of classes she registered for only one course with money my seamstress grandmother had skimmed from the household budget. When my mother met my father a few years later in New York, he exuded the financial success and social class she so desperately wanted, though that pipe dream disappeared once they were married.

* * *

As I went through Dad’s crowded drawers, I unearthed things as disparate as shot glasses from his Yale 1940 graduating class, pieces of Dentyne gum, golf tees, dehydrated snow globes picked up on family vacations, and outdated calendars from insurance and fuel companies. I found a package of condoms and a well-thumbed paperback of Coffee, Tea or Me? The Uninhibited Memoirs of Two Airline Stewardesses.

I intently studied the unpaid bills my father piled on his dresser. I fanned through canceled checks carefully bundled in their original bank envelopes. I liked my father’s neat, primary school print so much that I kept random checks to start another collection of things that didn’t belong to me. I coveted his elegant check registry as large as a coffee table book. Its brown leather was embossed in gold with KHB. I paged through lists of checks my father recorded, searching for signs of the bankruptcy towards which my mother screamed we were headed. My father, an accountant who organized other people’s finances, oddly enough had little success marshaling his own.

Stashed in his sock drawer, I found elaborate budgets he worked up with words like mortgage and heat floating between asterisks. On pieces of cardboard that came from the dry cleaner with his freshly pressed shirts, he printed the names of stores my mother frequented in red capital letters. It was as if he was symbolizing that her shopping was bleeding us dry.

“The doctor can prescribe something else for your nerves,” my father murmured.

But shopping was a balm for my mother and me. On Saturday afternoons we ended up in downtown Hartford. My mother went to get her eyebrows waxed at G. Fox & Co., a utilitarian, yet elegant department store. When the elevator opened onto the eleventh floor, everything smelled of beauty. Afterwards we rode down on the escalators, stopping to buy sale dresses and support hosiery for my mother. Shopping at G. Fox came with the distinct privilege of bringing home the store’s crisp navy blue shopping bags. Yet my mother always pleaded poverty when I asked her to buy me something. “Mamá no tiene dinero” was her constant refrain. In response, I surveyed the terrain and stashed forty-fives or jewelry in the bags.

J.J. Newberry, a five and dime store, was easier to steal from. Newberry—all linoleum floors and plastic bins—had a hectic array of lipsticks and eye shadows through which we sifted. By the time I was interested enough to pocket makeup for myself, few of us from the suburbs still ventured downtown. One Saturday, I watched a pair of Puerto Rican girls, slick and confident, shoplifting nail polish and lip gloss from Newberry. Their technique was flawless. Their next move? To filch my mother’s wallet.

“Mira esa vieja, que fea. Pero ella tiene plata.”

They didn’t expect a lady fresh off the A1 bus from West Hartford to understand them. As soon as my mother turned around, they knew they had underestimated her and her ire over being called old and ugly. My mother pulled the hair of the younger teenager, who was just a year or two older than I. The older one ran away.

“Say it again,” my mother said. “Dilo otra vez que yo soy vieja y fea,” she said, crazed and up close to the girl’s round face, “and I will take you to the policia, you ladrona.”

Though I never doubted my mother would turn me into the police, too, if she caught me stealing, I continued my petty larceny. I moved on to steal mostly drugstore makeup that I applied in the girls’ bathroom in junior high school. But as hard as I tried, I was not the effortless beauty my mother was. When I was little, I watched her put on her armor for a Saturday evening out. She began with a pointy bra and a heavy girdle with fasteners that snapped onto the reinforced tops of silky, shiny, shimmery stockings. She wore a glittery minidress and completed the ensemble with black boots that appeared as if they had been poured on her legs. She was the envy of my father’s friends with their plain older wives. And to me, she was simply the most beautiful woman in the world. “La mas linda della familia,” said my besotted father.

I often spied into my parents’ bedroom though the sliver of light and space between the door and doorjamb. There was a twenty-year difference between them—a gulf, a bay, maybe the Bay of Pigs— but the age divide always vanished when they danced a smoked, stoked cha-cha in the blue noir of cigar smoke and the stink of beer. Later that night as my father pulled off my mother’s boots, Mom on the bed, dreamy and sleepy, whispered, “Too much dancing.”

* * *

Forty years later, my father has been dead for a decade. I am once again in my mother’s closet. I am once again a detective, a thief. The clues I’ve been collecting for a lifetime have led me to the recent discovery that my father had been on the ground helping to engineer a coup in Guatemala in 1952.

The Treachery of Images. Nothing is a coincidence.

Treachery may be an extreme word for my father’s silence about his time in the CIA, a secret he took to his grave. I wish he had entrusted me with the lives he lived before I was born. But I was the all-too-curious kid who stole, and I think he knew that.

Although, officially, I am looking for papers I requested to prove my mother is eligible for Dad’s veterans’ benefits, I am also on the lookout for any evidence of my father’s presence in Guatemala. My mother does not know Dad was in the CIA. How can I tell her my father wed her on an assignment? His mission was to place himself in Cuba and marrying a Cuban national seemed a natural way to do that. But history went awry and my mother became pregnant with me on her wedding night. My father had to sit out the Bay of Pigs.

* * *

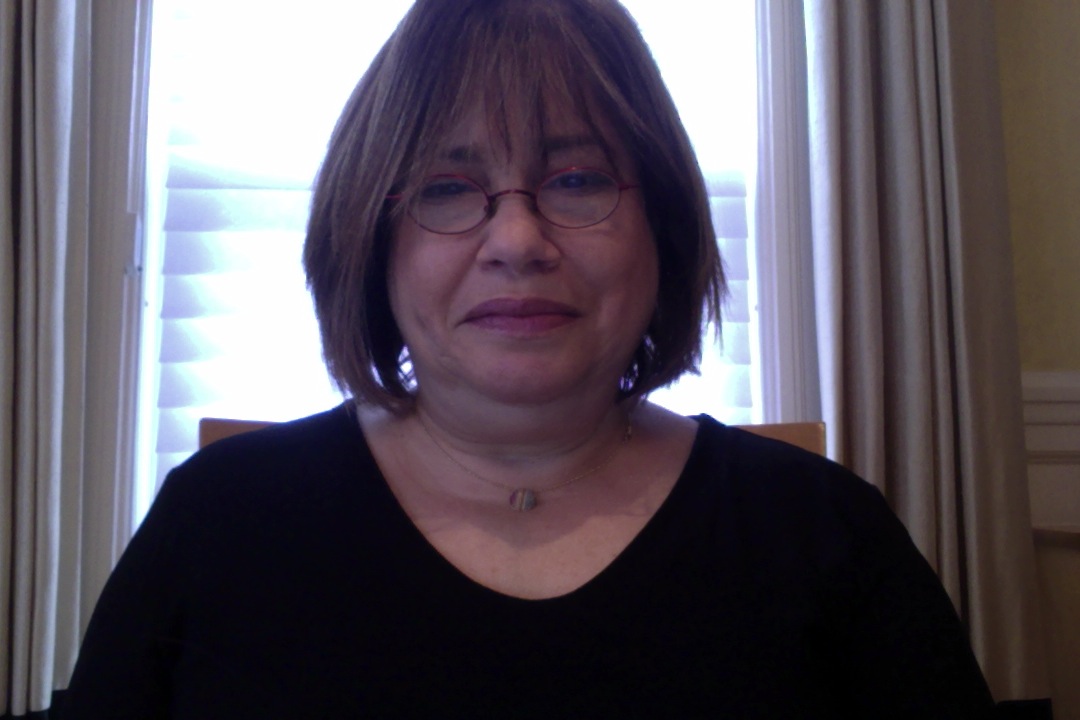

My mother has on contact lenses. Her frameless face reflects her desire to capture her once-upon-a-time beauty. But her green eyes now float among broken blood vessels. She wears black flats and leans on a cane. She stares at me sprawled on the floor and I am instantly reduced to the little outlaw girl playing dress up in her mother’s closet. The little girl who appeared so much smaller when she wore her mother’s heels or glimpsed herself in the reflection in her father’s aviator sunglasses.

“Que carajo—what the hell are you looking to take this time, Judy Bolton?” My mother uses my full, original name—my detective name—when she’s furious with me.

“I’m not sure.” All I know is I need to piece together a paper trail to prove she was married to Lieutenant Commander K. Harold Bolton. I’ve already written away for their marriage license the same way I filed a Freedom of Information Act for my father. But the CIA would neither confirm nor deny his affiliation with the agency.

I rifle through yellowed tax returns in brown accordion folders, financial information conveyed in Dad’s straightforward green-inked print. I sort through the uncharacteristically sugary, fancy long-ago birthday cards he liked to send us. I examine the credit card bills my mother accumulated from stores that are now shuttered. I hear my father’s echo: “The doctor can prescribe something for your nerves”

I steal a black and brown tweed shawl with a matching skirt. It’s a mid-century relic from my aunt, but Mom always wore it with verve and youth. I continue to rummage through the glamorous wreckage of clothes and the dust sends me on a coughing jag. This closet has become all past, with no touchstone to present or future.

I find the fuchsia sheath, tattered and streaked with neglect. The matching shoes are now stained; one of them has a broken heel. I can’t get the ragged slip over my chest, but I try anyway. My mother once starved to maintain her figure, never setting a place for herself at the kitchen table. Instead, she’d stand at the sink and eat scraps off our plates.

J.J. Newberry is gone, but the makeup we bought from its bins, now dried out and flaky, still crowds my mother’s ancient vanity. As a kid, I sat at that vanity, brushing circles of rouge on my cheeks and applying dark red lipstick until it looked like a scar slashed across my mouth.

The leather checkbook registry, stashed deep in my mother’s closet, is cracked. KHB—the initials once so stately and regal on its cover—are faded into near oblivion. It looks like time and condensation have blurred my father’s meticulous entries.

Just as Magritte declared his picture was not a pipe, this house is not the one in which I grew up. And yet the embroidered roses on my mother’s sheath—though wilted—are beautiful to me in the same way that a man who has loved a woman for decades stills sees her as young and pretty.

I fold the sheath and pack it with the shawl and skirt in a creased G. Fox bag. I grab some of the papers and cards, just to have my father’s inimitable handwriting near me again.

I still sleuth, I still steal.

I am, after all, Judy Bolton, girl detective and thief.