Klétka: The Story of Jenő Gold

[translated prose]

From the spring of 1986 onwards, Vera’s abdomen, stomach, or something thereabouts, hurt. It didn’t hurt all the time. It hurt sometimes. It didn’t even always hurt in the same way. At times, it hurt more; at other times, it hurt less. They thought: it happens. One’s stomach hurts sometimes. It will go away.

But weeks passed and it didn’t go away.

Vera’s pain hurt Jenő, too.

When we love someone, their pain hurts us.

Jenő loved Vera.

Her pain hurt him.

He would ponder this later. When the pain grew. How it was. With someone else’s pain. He didn’t get far with it. And later still he had no time to ponder such things at all. He had to march on; whether in pain or not, he had to march on.

But they were only at the very beginning.

They had just sunk their teeth into it.

First, they saw the classmate of Vera’s previous husband, an excellent man, an excellent doctor. A sort of kinsman, an ally, who examined, surveyed, asked, and, of course, knew everything. He also knew that this pain was to be expected. Of course Vera’s stomach hurt. We have to pay, sooner or later, for everything we have done in the past. In fact, her little stomach pain was a very friendly price for the monstrous act of treason she had committed against her ex-husband, which had left Vera with pain in her heart and in her stomach, with pain inside her body.

Such pain doesn’t show itself immediately. This sort of pain is delayed. It rears its head when one calms down. Relaxes. Stops being constantly on guard. When one takes off the armor, the mask, puts down the sword and shield. This is when such pain attacks.

It will go away. Until then, the pain only needs to be managed. Drink milk when it hurts. Or a shot of cognac. A few nips of Almagel will heal the problem completely.

It stands to reason, one cannot stress enough, that the pain exists. No wonder. That’s the least. That it hurts.

It hurts now, but it will go away. When things straighten out completely and forever, it will go away.

But this one somehow refused to go away, this pain. Or only very slowly. Months went by and it still hurt.

And there was another bump in the road: that things also refused to straighten out—at least, not completely and not forever.

One couldn’t really relax.

Straightforward, clear and without doubts Jenő and Vera’s relationship might have been; around them, the world was chaotic, doubtful, turning into tragedy.

And Vera’s stomach continued to hurt.

She kept marching on, composed; she lived, taught, cooked, went out with Jenő, but in the midst of all this, her stomach hurt every day, or at least something inside her hurt nearly every day.

In the meantime, her doctor had moved to the US.

The Golds did have a doctor—wonderful, extraordinary, peerless. Erzsike. As for her origins, she was the sister of Mihály Gold’s secondary school classmate. But Vera refused to see the doctor who, as head of unit, also had a hospital background. “I’ll be damned if I ever see your stupid father’s doctor,” she would say.

In the end, they found a decent young man, a gastroenterologist, who prescribed all sorts of medicines. As Vera gulped them down, sometimes the pain seemed to ease. Sometimes it seemed so. And sometimes it didn’t.

Then one night before New Year’s Eve in 1986, Mihály went to the toilet, only to come back with an ashen face a quarter of an hour later. He didn’t drink a drop on New Year’s Eve and by the 3rd, he was already in the János Hospital. As inevitably happens, they found polyps inside him… And something else. The bleeding had been caused by the polyps that were later removed, but something else was only found accidentally as some sort of bonus. Perhaps if they hadn’t found it, Jenő’s father would have… But let’s not go there.

On 6 February, Mihály was operated on by Dr. Stern. There was no metastasis: a reprieve of more than five years was granted.

Vera’s stomach hurt nonetheless; it continued to hurt; it hurt all through 1987.

Unwavering, she carried on teaching.

At the end of the school year, she took her class to a Budapest canning factory for what was then known as “public contribution.” Having returned home afterwards, she reported back to Jenő.

“It was astonishing, Jenő, truly astonishing. Firstly, you’ve never seen that level of filth ever in your life. There was water, rubbish, muck, grime, slime, sludge everywhere. In the rooms: unbearable heat and unbearable drafts. Unbroken windows? Maybe none. Astonishing. There were the work leaders—three or four of them—well, they don’t do a thing. But they have their own toilet, cafeteria, shower, and telephone. They earn three times as much as those who actually work. They’re bossing the others around, and they’re smoking and drinking coffee. They receive their orders on the telephone from somewhere high up. Then there are the toilers. Nearly all of them from Acsa. That’s a village near Galgamácsa. That’s where they commute from every day. They work ten to twelve hours a day in the factory and commute four hours a day. Their pay is three to four thousand Forints. Loads of children among them, too. Same age as my pupils. Mine worked damned decently and they behaved damned decently with those people from Acsa. They were flipping decent and sweet. I’ve never had such a good class in my life, Jenő, ever…”

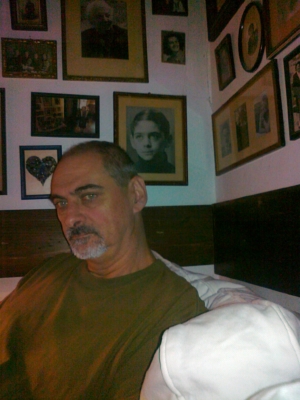

It was late in the afternoon on Tuesday, 24 November 1987. Taking stock of her day, Vera was lying on the bed, which Jenő had made with his own hands the previous summer, and which consisted of a double mattress placed upon a makeshift plywood platform; she was tired, but—right now—cheerful.

Vera had become head of a new class in September, the third in her teaching career. Those who know, know what it is like to be a class teacher. To be sure, those who know, also know that this business necessitates some degree of luck. Because—no matter how unjust such a generalization is on an individual level—there are good classes and there are not so good ones.

Vera had loved many of her pupils before, she had loved many of them greatly, but it was the first time that she had loved an entire class, her own, truly and without reservations.

Due to an extraordinary coincidence, this class purely consisted of intelligent, inquisitive, original pupils. They adored Vera, and she was equally passionate about them.

Talking about this class in a torrential river of words, she lay on the bed under the photo wall, smoking one cigarette after another. Taking her pupils one by one, she analyzed how each had behaved in the unfamiliar situation; how they had coped with the depressing atmosphere, with the task at hand, with the never-before-seen laborers. It was the twins she was talking about most: her secret favorites, the two handsome boys, who only she, among all the teachers, could tell apart, and who were a bit of an oddity in the well-heeled school in Budapest. Their father was a dyke keeper on Szentendre Island; the boys took the ferry to school every day.

Vera talked and talked.

And Jenő couldn’t help but admire Vera. He admired her because she was beautiful, stunningly beautiful, even after losing fifteen kilos, even with her larger than normal eyes, with cheeks ravaged, sunken with pain. Jenő admired Vera for being able to focus on her pupils to such an extreme degree, for still showing so much empathy, for harboring such a naturally deep, bottomless sense of social awareness.

“One of the tasks was sorting cucumbers, which was an unbelievably crazy job. There was this huge mountain of cucumbers and we had to sort out the good ones, and throw away those that were rotten, moldy or wormy. Imagine the foulest job ever, and you’ve got it. Still, the children did it without a word of complaint. And while we were at it, we chatted to these people from Acsa and I had a little group around me. I was getting on particularly well with a boy called Józsi. He was such an awfully sweet lad; only fifteen, but he works fourteen hours a day. Ouch, this pain. I had no idea such things existed, working fourteen hours on end. And a child, too. It was like something by Engels coming to life. Józsi asked where these beautiful girls went to school—of course, he didn’t dare to talk to them. I said, in Buda. He asked, where in Buda. I said, next to the Round Hotel. The Round Hotel? He had never heard of it. He was asking all the women laborers, but there was no one who knew what it was and where it might be. The Round Hotel. So I said, by the cogwheel railway. Still nobody knew. And what do their parents do, asked Józsi. What could I say to him? Foreign affairs, foreign trade? I looked at the twins, who by the way were working like carthorses. And I said, water works, for example. And where do they live? What do you mean, where? So, in a hostel or in rented rooms? I said… Ouch…”

“What is it?”

“I have this horrible stomach pain again. Let me just take an Algopyrin. Please bring me some water.”

Jenő went out, filled a glass with water and while he was in the kitchen, he made himself a spritzer and took the two glasses back to their corner room. Vera was lying on the bed with her shirt pulled up on her stomach, the top buttons of her jeans undone.

“What are you doing?”

“Give me your hand,” she said. Kneeling on the bed beside his wife, Jenő laid a hesitant hand on the stomach. Vera held the hand and pressed it firmly on the area just below the navel, to the right. Jenő could make out a hardening. A lump. A thing.

“What’s that?”

“Something. You must have eaten too much,” Jenő said nervously and left the room. Once outside, he discussed the matter with his mother, father, and sister, then took the telephone into his sister’s room and dialed. At seven the following morning, they were already in a queue in front of the first floor office of Gastrointestinal Unit 1.

Vera didn’t set foot in the school for the rest of the year. In the following year, she taught a couple of hours, or at least she was there, but, needless to say, she couldn’t carry on as head of class any longer. The teacher who took over found the pupils troublesome; they had become unruly, difficult.

Jenő, too, went to school less frequently after this.

He went to the hospital. He did hospital.

Of course, going to the hospital is still better than being in hospital.

Not that you can call it a good thing, either. To do hospital. To go to the hospital.

From the end of 1987 until the autumn of 1993, he was essentially a professional hospital goer.

His father, mother, and wife had cancer all at once. How to measure the amount of time Jenő spent visiting them? More than once, and for considerable periods of time, he had to visit hospitals in two different directions. At other times, two of his loved ones happened to be staying in the same unit simultaneously. This spared Jenő an awfully lot of tram rides.

There was hardly a hospital in Budapest which Jenő and his sister, with whom he performed the task of doing hospital, didn’t visit at one time or another in the proceedings. As for the János Hospital, they came and went almost as if every unit were their home.

It so happened that Jenő did have time to do hospital; he had stopped teaching after winning a monthly literary stipend of 3,000 Forints. He wrote bits and pieces occasionally, but he mainly did hospital. He had become a stipended hospital goer.

He learned all too well what it meant: to do hospital.

First and foremost, it was a task that demanded all one’s energies.

To do hospital is to go to the hospital.

To other places, too, but only afterwards.

The life of someone who does hospital is determined, framed, enclosed by the daily experience of doing hospital.

To do hospital, at least in Hungary, is not child’s play and there is a great deal at stake.

To do hospital requires all one’s energies. All the energies of a strong, healthy person, one could add.

“We’ve won this battle,” Dr. Stern said without enthusiasm as he stepped out of the operating theatre, where he had operated on Vera for the first time.

The surgeon was right: doing hospital is war. There are battles and truces, peace treaties and ambushes, councils of war and rulings that cannot be challenged.

There are also the odd victories. Trouble is, these are very rare.

Those lying on hospital beds surrender themselves to their doctors and, chiefly, to their loved ones, if they have any. It is a rare thing, indeed, for patients to move things forward themselves, for them to make cardinal decisions about themselves.

That’s what the others are for, those who do hospital.

Doctors and nurses have more than enough on their shoulders—not much of their time or strength is left to sweat over the troubles of others.

Those who do hospital must always decide by themselves.

Left to our own devices, we must rely on ourselves at every turn; every important decision must be made by ourselves, too.

A doctor may very well be wonderful—perhaps a whole unit is run in an exemplary manner—but there’s no guarantee whatsoever that this will be the case at the next stage. Indeed, there is no guarantee that the patient will automatically proceed to the next stage. And even if they do, that they will go to the right place. All these details must be driven, controlled by those who do hospital.

Manual control over the procedure is imperative; nothing can be surrendered or allowed to proceed on its own way as nothing has its own way. For there is no order, no system, or where there is, it doesn’t work.

To do hospital demands unwavering vigilance.

Attention must be paid to everything; one must, with all one’s might, pay attention to all the details. Is there loo roll, medicine? Are there enough cotton pads, tampons? Has the infusion finished? Is the bedpan, the bag full? One must ensure that complications never strike on a Friday. An ugly mistake that would be, having complications on Friday. A grave problem. Monday? Not much better as there will be crowds of people waiting. It’s advisable to wait until Tuesday for bleeding, cramps, attacks.

One must be well versed in the local tricks of patient transport; able to deal with porters; familiarize oneself with the trials and tribulations of the children of key nurses. Reliable local knowledge is essential: every hospital teems with back doors, exit routes, and secret corridors.

Yes, one must devote time to do hospital. All one’s time.

The hospital doer can’t get away without standing, sitting, lying in queues. The same goes for the hospital doer who otherwise has good connections.

The time of the patient and that of the hospital doer becomes dislocated.

No one is to blame. That’s what the system is like. Timeless.

Those who lie in hospital beds will either come out one day or they won’t. But the hospital doer comes out daily. Yet outside he moves differently to those who do not go to the hospital day after day. The hospital doer carries the hospital inside him into the outside world.

Doing hospital for six years, not to mention the way the whole affair ended, determined the rest of Jenő’s life. Not that he lived differently afterwards, rather that he lived life differently.

It’s true, doing hospital has certain advantages.

No more headaches over how to spend free time. There is no need for the hospital doer to go on holiday; no need to go far, for the hospital doer it makes no difference whether it is spring or summer, autumn or winter.

The activity of doing hospital is known for its character-shaping and educating powers. It teaches one fastidiousness and discipline. And while doing it perfectly is next to impossible, doing hospital has the bonus of eroding all traces of self-conceit.

But here’s the glitch: doing hospital is a sad occupation. The hospital doer is saddened. Sadly does he go about his business, leave a clean set of clothes, bring back the dirty laundry, stock up on fruit juice; sadly does he set off, get in the car, get on the tram, greet the porter who now barely looks up to wave, the cleaner, the nurse, or the doctor, who’s always leaving when we arrive, God only knows where to.

The hospital doer sadly goes, sadly does; sadly does he come back along the road, under the giant sycamores…

And sadly does he go back to his life, sadly does he drink his hospital-insulating beer, sadly does he buy his life-sustaining bread, sadly does he arrive home, sadly does he cook, feed, eat, and drink, stumble and rise, come and go, live, hurt, love.

Trouble is, doing hospital makes one sad. And above all, while doing hospital will eventually come to an end—it might, just, come to an end—the sadness never will. It will never go away. It will stay. This is the problem when it comes to doing hospital. This. And many more besides.

![]()

KLÉTKA

1986 tavaszától Verának fájt a hasa, gyomra, valamije.

Nem mindig fájt. Néha fájt. Nem is mindig egyformán fájt. Hol jobban, hol kevésbé fájt. Gondolták, van ilyen. Az embernek fáj a gyomra néha. Majd elmúlik.

De teltek a hetek, és nem múlt el.

Jenőnek is fájt a fájás.

Akit szeretünk, annak fájása fáj.

Jenő nagyon szerette Verát.

Fájt a fájása tehát neki is.

Ezen később töprengett sokat. Amikor még jobban fájtak a dolgok. Hogy is van ez. A másik fájásával. De nem jutott sokra. Később pedig már ideje sem volt töprengeni ilyen dolgokon. Csinálni kellett, ha fájt, ha nem, csinálni.

De akkor még csak az elején tartottak.

Éppen csak hogy belekezdtek.

Először Vera volt férjének osztálytársához, nagyszerű emberhez, nagyszerű orvoshoz mentek el. Afféle testvér volt ő, szövetséges, aki vizsgált, nézett, kérdezett, és persze mindent tudott. Tudta azt is, hogy mi sem természetesebb e fájásnál. Még szép, hogy fáj a gyomra Verának. Mindenért fizetni kell, előbb vagy utóbb, mindenért. Ezzel a kis gyomorfájással még olcsón is van megszámítva egy akkora árulás, mint amekkora Vera lelkén, gyomrán vagy mijén száradt, ugye.

Az ilyen fájás nem rögtön jön elő. Az ilyen fájás késleltetett fájás. Akkor veszi kezdetét, amikor megnyugszik az ember. Kienged. Megszűnik résen lenni folyton. Amikor leveti a páncélt, a maszkot, leteszi a kardot, a pajzsot. Akkor támad az efféle fájás.

Majd elmúlik. Addig pedig karban kell tartani a fájást csupán. Tejet kell inni, ha fáj. Vagy egy stampedli konyakot. Pár nyelet almagél pedig végképp ír lesz a bajra.

Ami – nem lehet hangsúlyozni eléggé – magától értetődik. Még szép, hogy van. Az a legkevesebb. Hogy fáj.

Most fáj, de majd elmúlik. Ha a dolgok teljesen és végképp rendbe jönnek, elmúlik.

De ez valahogy nem akart elmúlni, ez a fájás. Vagy nagyon lassan. Teltek a hónapok, és továbbra is fájt.

És volt még egy bökkenő, hogy a dolgok sem igen akartak rendbe jönni, legalábbis nem teljesen és nem végképp.

Nemigen lehetett megnyugodni.

Mert hiába volt egyértelmű, tiszta, kétségtelen a kapcsolat kettejük között, ha köröttük zavaros, kétséges, bajba forduló volt szinte minden.

Verának pedig fájt a gyomra.

Csinálta a dolgokat, csinálta fegyelmezetten, élt, tanított, főzött, eljárt Jenővel, de közben fájt a gyomra, mindennap, vagy majdnem mindennap fájt a gyomra vagy mije.

Orvosa közben Amerikába helyezte át székhelyét.

A Goldoknak volt orvosuk, csodálatos, különleges, párja nincs. Erzsike. Eredetét tekintve Gold Mihály gimnáziumi osztálytársának húga. De az osztályvezető, tehát kórházi háttérrel is bíró doktornőhöz nem volt hajlandó elmenni Vera. „Hülye apátok orvosához én nem megyek” – mondta.

Találtak végül egy derék fiatalembert, gasztroenterológust, aki felírt mindenféle szert. Szedte, nyelte Vera azokat, és néha mintha a fájás enyhült volna. Néha úgy tűnt. De aztán máskor meg úgy tűnt, hogy nem enyhül.

1986 szilveszterének előestéjén aztán Mihály kiment a mellékhelyiségbe, és negyedóra múlva hamuszürke arccal tért vissza onnan. Szilveszterkor egy kortyot sem ivott, harmadikán befeküdt a Jánosba. Ahogy az már lenni szokott, mindenféle polipokat leltek benne… És még valamit. A vérzést a később eltávolított polipok okozták, a még valami csak afféle bonuszként került meg véletlenül. Lehet, hogy ha nem veszik észre, akkor… De hát ez fölös beszéd.

Február 5-én Stern doktor megoperálta. Nem volt áttét, több mint öt év haladék adatott.

De Verának ettől még fájt a gyomra, fájt továbbra is, fájt 1987-ben egész éven át.

De azért tanított még rendületlenül.

Év végén osztályát egy pesti konzervgyárba úgynevezett társadalmi munkára vitte. Hazatérve referált Jenőnek.

—Elképesztő volt, Jenő, elképesztő. Először is ilyen mocskot te még a büdös életben nem láttál. Mindenütt víz, szemét, trutyi, gané, lepedék, lucsok. A helyiségekben elviselhetetlen a meleg, és elviselhetetlen a huzat. Ablak, amelyik nincsen kitörve, olyan egy sincs talán. Elképesztő. Vannak a munkavezetők, hárman, négyen, ők nem csinálnak semmit. Viszont van külön vécéjük, külön kávézójuk, zuhanyozójuk, telefonjuk. Háromszor annyit keresnek, mint azok, akik dolgoznak. Ők csak dirigálnak, cigarettáznak és kávéznak. Telefonon kapják az utasításokat valahonnan odafentről. És vannak a melósok. Majdnem mind acsai. Az egy falu valahol Galgamácsa mellett. Onnan utaznak be naponta. Napi tíz-tizenkét órát dolgoznak a gyárban, és napi négy órát utaznak. Fizetésük három-négyezer forint. Van köztük egy csomó gyerek. Annyi idősek, mint az én gyerekeim. Akik baromi rendesen dolgoztak és baromi rendesek voltak ezekkel az acsaiakkal. Állati rendesek voltak, állati aranyosak voltak. Nekem még soha ilyen jó osztályom nem volt, Jenő, soha…

Így mesélt 1987. november 24-én kedden, késő délután. Az ágyon feküdt, amit Jenő enkézzel készített a nyáron, a furnérlapokból tákolt dobogóra helyezett kétszemélyes matracágyon feküdt, fáradtan, de kivételesen jókedvűen.

Verának szeptembertől új osztálya lett, pedagógiai pályája során a harmadik. Aki tudja, tudja, milyen hivatal az osztályfőnöké. És aki tudja, az tudja azt is, hogy ehhez a hivatalhoz szükséges bizony némi szerencse is. Mert – bármily igaztalan az efféle generalizálás az egyénre nézve – van jó osztály, és van kevésbé jó.

Sok tanítványát szerette Vera, sokat szeretett nagyon, de egy egész osztályt, sajátot, igazán, fenntartás nélkül, most szeretett először.

Ebbe az osztályba valami fatális véletlen folytán csupa értelmes, érdeklődő, eredeti gyerek került. Verát szerfelett szerették, és ő lelkesedett értük.

Róluk beszélt tehát, ömlött a szó belőle megállíthatatlanul, miközben feküdt az ágyon, a fényképfal alatt, és egyik cigarettát szívta a másik után. Tanítványait egyenként véve sorra, elemezte, melyik hogyan viselkedett a furcsa helyzetben; ki hogy bírta a nyomasztó miliőt, a munkát, a sosem látott kétkezi népet Különösen sokat mesélt titkos kedvenceiről, az ikrekről, a két helyes fiúról, akiket az összes tanár közül csak ő tudott biztosan megkülönböztetni egymástól, és akik kilógtak a budai iskolából kissé: apjuk gátőr volt a Szentendrei-szigeten, onnan is jártak be naponta, komppal.

Beszélt Vera, beszélt és beszélt.

Jenő csak csodálta Verát, csodálta, mert szép volt, nagyon szép, még tizenöt kilónyit fogyva is szép, megnőtt szemmel, a fájdalomtól megviselt, beesett arccal is. Csodálta Jenő Verát, hogy így képes figyelni tanítványaira, hogy ennyi empátiával bír még mindig, hogy ilyen természetes, mélységesen mély szociális érzék munkál benne.

—Uborkaválogatás volt az egyik munka, hát az valami eszelős, hatalmas hegynyi uborkából kellett válogatni a jót, és szétdobálni a rothadtat, penészest, kukacost, ha láttál már ótvar munkát, no hát ez az volt, és a gyerekek csinálták zokszó nélkül, közben diskuráltunk az acsaiakkal, egész kis cercle képződött körém, különösen egy Józsival barátkoztam össze, állati helyes kölyök volt, tizenöt éves, napi tizennégy órát dolgozik. Jaj, de fáj. Nem is tudtam, hogy van ilyen. Tizennégy órát dolgozni egyvégtében. Egy gyerek. Mintha egy Engels-passzus elevenedett volna meg. Kérdezte, hová járnak iskolába ezek a gyönyörű lányok, akikhez persze nem mert szólni. Mondtam, Budára. Kérdezte, azon belül hova. Mondtam, a körszálló mellé. Körszálló, sose hallott róla. Kérdezte az asszonyoktól, de nem volt senki, aki tudta volna, mi az, és hol lehet. Körszálló. Mondtam, hogy a fogasnál. Úgy sem tudta senki. És mivel foglalkoznak ezeknek a szülei, kérdezte Józsi. Most mit mondjak neki? Hogy külügy, külker? Ránéztem az ikrekre, akik mellesleg úgy dolgoztak, mint az állat. Mondtam, hogy például: vízügy. És hol laknak? Hogyhogy hol? Hát szállón vagy albérletben? Hát mondtam… Jaj…

—Mi van, Vera?

—Nagyon fáj a hasam. Beveszek egy Algopyrint. Kérlek, hozz vizet.

Jenő kiment, töltött vizet, ha már kinn volt, készített magának egy fröccsöt is, úgy ment vissza a sarokszobába a két pohárral. Vera az ágyon feküdt, inge felhúzva hasáról, farmerja ki volt gombolva felül.

—Mit csinálsz?

—Add csak ide a kezedet – mondta. Jenő odatérdelt felesége mellé az ágyra, és kezét a hasra tette bizonytalanul. Vera megfogta a kezet, és odanyomta a köldöktől kicsit lejjebb, jobbra, jó erősen. Jenő valami keményedést érzett. Dudort. Valamit.

—Mi ez?

—Valami. Biztos sokat ettél – mondta Jenő idegesen, és kiment. Odakinn egy kicsit konzultált anyjával, apjával, húgával, aztán bevitte a telefont a húga szobájába, és tárcsázott. Másnap reggel hétkor ott sorakoztak az egyes bel első emeleti irodája előtt.

Vera az évben többet nem tette be lábát az iskolába. A következő évben pár hónapot tanított még, legalábbis bejárt, de osztályát persze már nem kaphatta vissza. Aki átvette azt, nem boldogult vele; zűrös osztály lett, bajos.

Jenő is egyre kevesebbet járt már iskolába eztán.

Kórházba járt. Kórházazott.

Persze kórházba járni még mindig jobb, mint kórházban lenni.

De azért jónak az se jó. Kórházazni. Kórházba járni.

1987 végétől 1993 őszéig lényegében hivatásos kórházba járó volt.

Apja, anyja, felesége egyszerre lett rákos. Lehetett kórházba járni, képzelhető. Adódott úgy, nemegyszer, és nem is rövid ideig, hogy egyszerre kétfele kellett vizitálni. Adódott úgy is, hogy egyazon osztályon övéi közül egyszerre ketten is időztek. Nem kellett annyit villamosozni legalább.

Alig van olyan székesfővárosi kórház, ahol Jenő és húga, akivel együtt csinálták végig a processzust, meg ne fordultak volna. A János-kórháznak meg szinte valamennyi osztályán otthonos lett a mozgás.

Jenőnek éppen lett is ideje a kórházazásra – abbahagyta a tanítást; elnyert egy havi háromezer forintos irodalmi ösztöndíjat, néha írogatott is, de főleg kórházazott, ösztöndíjas kórházba járó volt.

Jól meg is tanulta, milyen az: kórházazni.

Mindenekelőtt: egész embert kívánó.

A kórházazó az kórházba jár.

Máshova is. De csak aztán.

A kórházazó életét meghatározza, keretezi, átfogja a napi kórházazás. A kórházazás, legalábbis Magyarországon, nem gyerekjáték és nem is babra megy.

A kórházazás teljes embert kíván. Mondhatnánk, erős, egészséges embert.

Ezt az ütközetet megnyertük – mondta minden lelkesedés nélkül Stern doktor, mikor kilépett a műtőből, ahol először operálták Verát.

Jól mondta a sebész: a kórházazás háború. Csaták vannak és fegyverszünetek, békekötések és orvtámadások, haditanácsok és fellebbezhetetlen ítéletek.

Győzelem is van. Csak nagyon ritkán, az a baj.

A kórházban fekvő megadja magát orvosainak, és mindenekelőtt: övéinek, ha vannak. Ritka az a beteg, aki maga veszi kezébe a maga ügyét, aki a kardinális döntéseket maga felett maga hozza meg.

Az a kórházazó dolga.

Az orvosnak, ápolónak van baja épp elég – ritkán jut idő, erő a máséval is bajmolódni.

A kórházazónak mindig magának kell döntenie.

Mindenben magunkra vagyunk utalva, hagyva, minden fontosabb döntést nekünk kell meghozni.

Lehet, hogy egy orvos nagyszerű, lehet, hogy egy osztály példamutatón működik; de a következő stációnál már egyáltalán nem biztos, hogy ez lesz a helyzet. És egyáltalán nem biztos az sem, hogy automatikusan továbbkerül a beteg. És ha kerül, az éppen megfelelő helyre kerül. Ezt mind-mind a kórházazónak kell tudnia vezérelnie, kontrollálnia.

Kézi vezérelni kell az ügymenetet, semmit sem szabad elengedni, hagyni menni a maga útján; mert nincsen maga útja semminek. Mert nincsen rend, nincsen rendszer, és ha van, az akkor nem működik.

A kórházazás lankadatlan figyelmet követel.

Ügyelni kell mindenre, mindenre magamagának kell az embernek ügyelni. Van-e klozetpapír, vatta, tampon, gyógyszer éppen. Nem csepegett-e az infúzió le. Megtelt-e az ágytál, a zacskó. Ügyelni kell rá, hogy soha ne üssön be baj pénteken. Az csúnya hiba, pénteken bajba kerülni. Az nagy baj. Még a hétfő sem az igazi, mert akkor rengetegen vannak. Kedden tanácsos kapni vérzést, görcsöt, rohamot.

Ismerni keli a betegszállítás honi fortélyait, tudni kell bánni a portástársadalommal, tisztába kell jönni a fontosabb ápolónők gyermekeinek gondjával, bajával. Fontos a jó helyismeret is; minden kórház teli van hátsó bejáratokkal, menekülő-útvonalakkal, titkos folyosókkal.

És a kórházazásra rá kell szánni az időt. Az egészet.

A kórházazó sorban állás, sorban ülés, sorban fekvés nélkül nem úszhatja meg. Még a protekciós kórházazó sem.

A beteg és a kórházazó ideje kizökken.

Nem tehet senki erről. Ilyen a rendszer. Időtlen.

Aki kórházban van, vagy kijön ormán egyszer, vagy nem. De a kórházazó mindennap kijön. De másként mozog odakinn, mint aki nem jár be naponta. Magában hordja a kórházat odakint is.

A hatévnyi kórházazás, no meg az, ami az egésznek a vége lett, meghatározta Jenő hátralévő életét is. Nem másként élt aztán, hanem másként élte meg az életet.

A kórházazásnak persze vannak jó oldalai is.

Nem kell többé spekulálni, mit kezdjen magával az ember. A kórházazónak nem kell mennie nyaralni, nem kell messzire menni, a kórházazónak egyre megy: tavasz van- e, vagy nyár, ősz-e, avagy tél.

A kórházazás alakítja, neveli az embert. Pontosságra, fegyelemre szoktat. És mivel tökéletesen csinálni bajos, gyorsan koptat mindenféle önteltséget is.

A bökkenő csupán az, hogy a kórházazás szomorú dolog. A kórházazó elszomorodik. Szomorúan végzi dolgát, tesz be tisztát, visz haza szennyest, táraz be üdítőt, szomorúan kél útra, ül kocsiba, száll villamosra, köszönget a portásnak, aki már csak éppen int, takarítónak, ápolónőnek, orvosnak, aki fene se tudja, hol szolgál amúgy, de mindig olyankor megy el, amikor mi éppen érkezünk.

A kórházazó szomorúan megy, szomorúan csinál, szomorúan jön vissza is végig az úton, a hatalmas platánok alatt…

És szomorúan megy az életbe vissza, szomorúan issza meg kórházszigetelő sörét, szomorúan veszi meg az életkenyerét, szomorúan érkezik haza, szomorúan főz, etet, étkezik, vétkezik, tesz-vesz, jön-megy, él, bánt, szeret.

Elszomorítja az embert a kórházazás, ez a baj. És az mindenekelőtt, hogy míg a kórházazás elmúlik, elmúlhat, esetleg, a szomorúság már soha. Az többé nem múlik el. Az marad. Ez a bökkenő, ami a kórházazást illeti. Ez. Ez is.

TRANSLATOR’S STATEMENT

“I found she took up residence in my life with such intensity that it was impossible to forget her breath-altering sentences,” writes Idra Novey in her Preface to Clarice: The Visitor (London: Sylph Editions, 2014) about the profound and at times disturbing effect Clarice Lispector’s voice had on her while Novey was translating The Passion According to G.H. I have been visited by the voice of Iván Bächer with similar intensity since I first read one of his mesmerizing collections of feuilletons on loss, absence, and want in a god-forgotten Hungarian village back in 2004. Just as Novey had done with Lispector, I have also read virtually everything Bächer had published, with some passages indelibly imprinted in my memory. The most mundane, everyday happening will bring his feuilletons to my mind. Listening to my gourmet of a husband talk about sausage making will inevitably lead me to recite bits of “Home electrocution,” a hilarious romp of DIY-sy pig slaughter. Hearing the loudspeaker at Keleti Railway Station in Budapest will make me think of Bächer’s train stories; while nursing a sick child, Bächer’s assertion, “when we love someone, their pain hurts us,” will ring achingly true.

It is “[a] true beholding” when Jenő Gold, the protagonist of the semi-autobiographical serial novel Klétka, sees his future wife for the first time. For me, the phrase has become a metaphor for translating the novel. This ostentatiously archaic and “odd” phrase sums up my twofold translation aim. First, I wanted to produce a translation that allowed the reader to “behold truthfully” my reading of Klétka, a deadpan story of heart-wrenching loss. “Truthfully” here does not refer to the problematic concept of word-for-word translation. Rather, it points to a reflection of my own reading of the novel. Indeed, it is the complex and deep affinity I have for Bächer and his book that fueled my translation, and I aimed to recreate in English the effects the original had had on me.

Secondly, I aimed to explore the extent to which a Bächeresque novel could be reproduced in a language and culture that do not know Bächer. The winding, at times contorted sentences, adverbs appearing in the least unexpected positions, the multitude of archaic and dialectal words and expressions add to a vibrant, ironic, movingly candid, albeit detached and aloof, but always sweepingly powerful style that is unmistakeably Bächer’s. I strove to keep this style, the pain seeping through the deadpan language, through neologisms, irony, a strategic use of repetitions, and the retention of the jagged sentence structure, where long sentences are punctuated by short, rapid ones.

Translating Bächer has been an intensely emotional exercise that in the not-too-distant past also involved exhilarating conversations with the author. Since Bächer’s death in 2013, I’ve been making do with his voice for companion.

Iván Bächer (1957-2013): Hungarian newspaper columnist and writer, he followed the tradition of the continental feuilleton or essay. He wrote about a variety of topics: history, politics, artists, scientists, musicians, food, and everyday life in the capital and in the countryside. His deadpan language laced with irony and his trademark black humor was cherished by a vast readership. Bächer’s most acclaimed works include his “family histories:” a series of four novels following the lives of his bohemian ancestors throughout the 20th century, offering a historical, social, and political panorama, as well as the minutiae of everyday life.

Veronika Haacker-Lukacs (b. 1977) is a Budapest-born literary translator interested in contemporary Hungarian prose and children’s literature. Her English translations of several of Iván Bächer’s feuilletons appeared in Budapest Tales (2009) and Hungarian Literature Online (2019), and a chapter from Judit Berg’s witty Two Tiny Dinos and the Magic Volcano also in Hungarian Literature Online (2020). She completed an MA in literary translation at the University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK, in 2019. She lives in Oxford, UK, with her husband and two young sons.