Lois Dodd, Painter

Lois Dodd was born in Montclair, New Jersey. She attended Cooper Union in New York City, where she started painting. She was part of the New York Tenth Street art scene in the 1950s and was one of the founders of the Tanager Gallery in 1952. Her works are found in many museums, including the Portland Museum of Art, Maine; the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri; and others. Her most recent exhibition “Day and Night” was at the Alexandre Gallery in New York City from February 25 through April 2, 2016.

Lois Dodd was born in Montclair, New Jersey. She attended Cooper Union in New York City, where she started painting. She was part of the New York Tenth Street art scene in the 1950s and was one of the founders of the Tanager Gallery in 1952. Her works are found in many museums, including the Portland Museum of Art, Maine; the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri; and others. Her most recent exhibition “Day and Night” was at the Alexandre Gallery in New York City from February 25 through April 2, 2016.

Ron Burch interviewed Lois Dodd by telephone on February 22, 2016.

* * *

Click the images below to enlarge.

History

Ron Burch: You have been part of one of the most exciting artistic periods: New York City in the 1950s and 60s. What was it like to be an artist then?

Lois Dodd: You see that’s what it looks like from here now. It wasn’t different than everyday existence now. Really. But, in retrospect, it was good. The art world was much smaller. That’s why it was what it became. It was so small. It was the uptown art world and the downtown art world, and you could know just about everybody in the downtown art world if that’s where you were. And that was probably true uptown as well. In that sense you felt very much part of a scene, which I’m sure artists have now, too. We all have our circles.

RB: What was it like to be a female artist at the time?

LD: (Laughs) Not being a male artist is hard enough. It was clear there were fewer female artists who were able to make a go of it than male artists. That seems pretty clear. In the group of friends that I had, it was not really a problem. Somehow, it didn’t come up.

RB: You were one of the founders of the Tanager Gallery, a collective that was part of the thriving New York City downtown art scene.

LD: I was the only woman of the five of us at the beginning. The gallery lasted about ten years from 1952-1962, but there were about 20 people over that period of time that became members of it. The other women were Sally Hazelet and Perle Fine. There were more men than women involved.

RB: Did the gallery help your artistic development or career or both?

LD: Oh, definitely. It did both. It provided a place to exhibit, and also, I was involved with running the place. Those of us involved went to see other artists’ work and made decisions about whom we would and wouldn’t show. We did a lot of visiting around to studios, and we saw what was going on at the time. It was very educational and informative and, again, was part of a community.

RB: I know Tanager and the other galleries on 10th Street had a strong community. Was it being able to exhibit or having a supportive artistic community that was more important to you?

LD: I think it was both. You can’t really separate them. It would be nice to have a community, but I also wanted the opportunity to show as well. That was equally important to me. That’s why we formed together to create the gallery, so that we could show our own work and the work of other people we found, thought were good, and needed a place to show. We were both providing a place for other people and showing our own work. And it was really very exciting doing that.

RB: Do you feel that, as an artist, having a community is essential?

LD: I do, yes. I think it’s very difficult, and maybe almost impossible, for an artist to be totally isolated. I think it’s very important to have a community.

RB: Have you had that community throughout your career? Did it change or dissipate after the Tanager closed?

LD: No, it really didn’t dissipate. There is an artist community here in the city and artists do keep in touch. If it isn’t just around the gallery, it’s all the friends that remained because of that association through the years. They go other places, but they’re still your friends. And you meet other artists and the other co-ops open and those have communities of artists. It’s a natural formation that happens.

RB: Did you critique each other’s works?

LD: No, that we did not do. We certainly discussed the work of people we chose to show with one another. I suppose that’s a critique in a way, but we weren’t busy critiquing each other’s work. We’d say, “It’s great.” That’s all your friends want to hear. (Laughs) They don’t want to hear what’s wrong with it. They can get enough of that in the outside world.

RB: Was there ever any pressure to meet the demands of the market?

LD: Not really. No. Somehow, that’s why we had the gallery. We didn’t want to feel that pressure. It wasn’t about that. Some people sold work, which was very nice, but it was kind of rare, actually, that in all the years of our existence we sold much of anything. It was not a place where we sold stuff.

Influences

RB: You were working in minimalist landscapes while those around you were producing abstract expressionism and pop art. Did your work go against the grain of fashion at that time?

LD: Well, I didn’t quite fit. I didn’t fit the abstract expressionists and I didn’t fit the realist painters either. But that seemed to be fine with my particular group of friends. I admired what the abstract expressionists were doing very much. And they were all around on 10th Street. [Willem] de Kooning had his studio there. Perle [Fine] had her studio there. A whole lot of them were right in that area. [Philip] Guston used to come by, and certainly, I admired all of their work.

At Cooper Union, the painting teacher that I had was very realistic himself, which he did not push on us in any way, shape, or form. And also the drawing teacher. They were both realists. I studied with them. I must have taken in what I learned from them. I never studied with anyone who was an abstract painter. So I think that had some effect.

RB: Were you ever influenced by the abstract or pop art?

LD: I was definitely influenced by the abstract painters because I really loved what they did. They definitely were an influence.

RB: But you kept to your style.

LD: I didn’t think of it as a style really. It’s just the way I painted. (Laughs) I was just trying to paint. Trying to look at the cows and get them down some way.

RB: Were you always confident about the way you painted? Did you ever have doubts?

LD: I suppose you always have doubts. But I don’t think you have a choice. The way you paint is the way you paint. I was not so facile that I could whip out different styles. There was never that choice.

RB: Over the years, have you noticed a shift in your work?

LD: I seemed to be better at being more realistic as I went along. In putting down more visibly recognizable things than back at the beginning.

RB: What do you think of this change?

LD: It seems to be an organic thing that happens. I don’t see it as myself making a conscious effort.

Process

RB: The ordinary, the commonplace, the everyday seem to be the bulk of your subject matter. What gets you started?

LD: I go outside. I drag my easel out there and I wander around and look for something that looks clear, something I can find, a composition that’s clear to me, and then I set myself up.

RB: Can you clarify what “clear” means?

LD: Something where there is some kind of geometric pattern or a light shadow, something that will fit onto a rectangle and break it up in a geometric way, basically underneath it all.

RB: Usually it’s the shape that gets your attention?

LD: Yes, yes, it is.

RB: The colors come after that?

LD: Yes, I’m out there pretty much using what I see. I’ve never been bold with a color to change what I see. I’m out there describing color-wise what’s in front of me.

RB: Once you find the shape, are you then working with what you see from nature?

LD: I’m trying to get it down before the light shifts so much, the shapes change. I’m in a battle with time and light and that’s why they’re pretty much two- to three-hour paintings, the ones that are on the panels, the panel paintings

RB: So everything you paint, it’s there. You don’t add to it?

LD: I don’t. I don’t know how to do that. I might leave something out. I’ve done that, but never added anything that I can think of.

RB: I read a quote from you that went: “It seems that once you really find what you want to paint, you can paint. Up to that point, you’re flailing around. It’s a very strange process, over the years. But once these things, subject matters, that attracted me presented themselves, it didn’t seem to be such a problem.” Would you speak more about that? Did your subject matter find you?

LD: (Laughs) No, but that’s an interesting thought. No, I find it. But it is from wandering around and looking at stuff. You know in the last so many years I’ve been working close to my place. I haven’t been getting in the car and driving to some location that I find exciting. I frequently would go to the Delaware Water Gap in New Jersey. But I felt like I used that up and I stopped going there. I’m pretty much right around my own place, both in Maine and the one in New Jersey. Here [in New York City] I’ve been painting out of the window this winter. I seem to be getting closer and closer to my own body.

The way you paint is the way you paint. I was not so facile that I could whip out different styles. There was never that choice.

RB: Has nature always been your primary subject matter?

LD: It’s funny. When I was in high school, I first went down to the railroad station, sat across the road and did a drawing, or it was a charcoal or pastel, of the building. So I did always like to work outside. It’s interesting. Not too keen on inside work. Although whenever I make a proclamation like that, the next thing I find is that I’m doing the reverse.

Clearly, I work from observation. That’s pretty clear. I can’t make anything up. I’ve never been totally abstract in that I could create on a blank canvas with absolutely nothing, just pulling it all out of my head. I’ve never been able to do that.

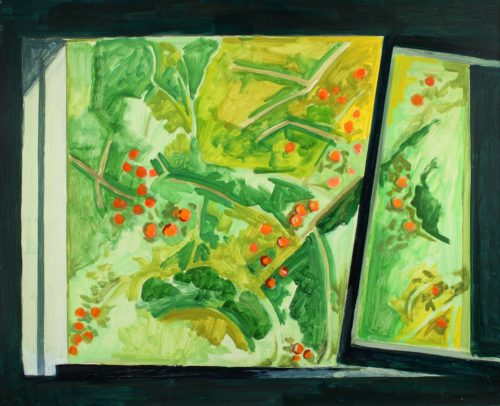

RB: Even though I know you do not consciously seek them out, most artists have themes that they are drawn to. Reflecting on your work, for example, it seems as if you keep returning to windows.

LD: Yes, I do. I seem to look up, and there’s an interesting thing out of the window so then I do another one. It’s often the same windows, but somehow I’m sitting at a different angle, or it’s a different time of day because I did all the windows at Second Street years ago but here I am looking out the window again but at night. It’s exactly the same windows, but they seem to provide more and more stuff to find.

RB: There is a lot of “framing” in your work: windows, tunnels, mirrors, even some of your hanging laundry paintings have that feel as we see in “Rainy Window NYC,” “Frosted Window,” “Pink Towel + Chicken House, June,” and the wonderful “Apple Tree through Barn Window, September.” What is it about this that appeals to you? What is it about closing off the frame or depicting frames within frames that appeals to you?

LD: I think it’s flatness. I think the one thing I got from the abstract painters was the idea of “flat.” I don’t want to create a huge depth. I like the idea that what I see there is flat. Close. Close space. Not distant space. Like the Delaware Water Gap because there are two overlapping mountains right in your face. And looking out the window is always good because there is always something right there that seems to be stuck to the window.

That’s the kind of thing I look for in nature. I don’t go to a mountaintop and look at a wonderful view. That does not appeal to me at all. I have to go someplace where it is overlapping and in my face, goes from top to bottom, and remains close and flat. I think I got that from the abstract painters. Everything had to be right on the surface. If you think of the abstract expressionists of the ’50s and ’60s, it was all flat. You can’t go into it and disappear miles away.

RB: It’s interesting to apply that to a landscape where there is depth.

LD: Yes, you pick and choose.

RB: So something else you just mentioned: time. You said you have to get a painting done before the sun moves and the light changes. How do you deal with the passage of time?

LD: As the hours go by, the shadows shift. I’m always aware that I’m trying to get the outline of any shadows or anything like that right away before it shifts because I was attracted to the way it looked at the moment I arrived. Not the way it will look by the time I leave. If things are moving too much, and shadows are shifting, I have to outline all that quickly in order to maintain the way it looked to me when I was first attracted to it.

RB: So you’re trying to capture that first moment you saw it?

LD: That’s right. It’s not that I’m there all month, painting it and incorporating a feeling of a long period of time. It’s the reverse.

RB: So even when you’re two hours in, you’re still trying to capture that original moment?

LD: Well, yes, I am. But I’m not in my head saying, Oh my God, I’ve got ten minutes. (Laughs) It’s not like that. It’s just that the light shifts, and it was the first light that I was attracted to. If it changes radically, I’m trying to remember what I originally saw at the beginning.

RB: And you are able to do that?

LD: Yes, I can do that in a two-to-three-hour period but more than that, no. I remember one time, I was painting the woods. And I was across the road from my house in Maine, and I set up large canvases because I discovered that I could not paint the woods on small panels. No way could I get the woods squeezed onto a small panel. It had to be fairly good-sized canvas. So I took them over there and at one point I had one set up for the morning light and another one set up in another location for the afternoon. I’d work in the morning on one of them, and in the afternoon, I’d go work on the other one because of the fact of the light moving so radically. You could kind of retain the information, maybe, two to three hours, but after that it’s so contrary to what you’re looking at, that you couldn’t keep working on the thing. So then, I’d go work on the other one.

It’s very difficult, and maybe almost impossible, for an artist to be totally isolated. It’s very important to have a community.

RB: Have you ever found another painting there after the light changes? Does one painting ever beget another?

LD: Yes, absolutely. I think that’s often the case. You realize there’s something new there. They move one into the other.

RB: I know that you have no narrative or social commentary associated with your paintings. What would you like the viewer to take away from a painting? An appreciation of form and color?

LD: Sure. Viewers bring their own sensibilities to it, so that’s their thing.

RB: So that’s something you don’t think about. You’re just trying to capture the moment.

LD: Right.

Day and Night

RB: In your latest exhibition at the Alexandre Gallery in New York, you have a new series called “Day and Night.” In it is a painting called “March Snowstorm.” I find the angle you chose to be really interesting. Did that just catch your eye?

LD: Yes, you have to move fast. Sometimes I feel like a reporter. Like the burning houses or snow coming down. You know it’s not going to keep doing that forever so you got to move and get going. Try to grab it while it’s happening. That’s exciting to me. I like to do that because something beautiful happens. Like a snowstorm.

RB: From the same show, “Night City Window” and “15 Night Windows” continue your interest with windows. How did you approach them? Did you paint each quadrant separately?

LD: I think so. I’m trying to remember. Did a blue look different in one quadrant than the other? (Laughs) Am I doing it one at a time? No, I’m drawing the thing first. Then I’m probably filling in the black of the buildings. But you’re right. Each quadrant you can think of as a separate unit and work on that. But it needs to be unified so it can’t get too separated in my head.

RB: There’s such symmetry to the windows. Is this how it happened?

LD: It’s a lie. It’s not like that out there. I left some out. I think one painting might be more accurate than the other. You can see that they’re the same building but they’re quite different. The window arrangement is not the same. And the one where they’re spaced further apart is probably more accurate. At night they only light certain windows, so you get this weird pattern. But then, on the other painting, I just made it a regular pattern.

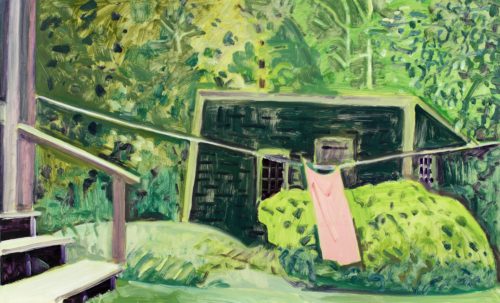

RB: When you did “Pink Towel + Chicken House” do you remember how that came about? Did the pink towel catch your eye?

LD: It was the pink towel. I might have hung it out on purpose. Because there was a point where I noticed the laundry and started painting it. Then I began to be self-conscious about it and hanging it out and I thought, “Gee, I want to have something red,” so I got my red curtains from upstairs and hung those out, and then maybe that towel was interesting to paint. Arranging the clothesline was like setting up a still life for me.

RB: Do you start with the towel or is it all drawn in at first?

LD: It’s all drawn in first, so it moves together, pulls together after it’s drawn in. But the thing that I liked about the towel was, again, that rectangular shape. It blocks out the whole middle and it squeezes the landscape around the edges. It’s right in your face. And it’s a flat rectangle, but you do get a little space around the edges, which I found intriguing to work with. The color is important, too.

RB: I’ve noticed in some of the recent paintings “Yellow Sun, Bare Trees” or “Sky Through Trees,” by filling the frame with trees, it seems that you are using the landscape itself as a frame. In a way, that which you’ve framed in the past is now part of the frame?

LD: Well, those are just tiny. You’re looking at the step flashings. Those I race out when I see something happening, and since they’re very tiny, it only takes fifteen or twenty minutes to get something down. And so, if the sun is doing something interesting, or the moon is doing something interesting, I can race out there and try to put it down.

RB: It’s the same kind of framing that you’re doing with your other work.

LD: It’s true, yes.

RB: You’re using the trees to fill the frame and squeeze that landscape again.

LD: Right.

RB: How do you know when you’re finished?

LD: When I start thinking that I’ll fix things, that’s when you know, “Stop it. Don’t do that.” You can’t fix anything. You’re done. When you start thinking “Okay, now I’ll just improve it . . .” It really doesn’t work for me. So, whatever I’ve had to say, when it’s done, it’s done. There’s nothing more to say about it.

RB: Do ever look at any of the older paintings and think, “I wish I had done this to it instead”?

LD: You know, I do that, and they don’t look any better. They look worse. It doesn’t really work trying to fix things. It just doesn’t work. Somehow, the initial impulse has to be fresh and right or else it’s just dead.

* * *

*Referenced Paintings:

1) Rainy Window NYC

2) Frosted Window

3) Pink Towel + Chicken House, June

4) Apple Tree through Barn Window, September

5) March Snowstorm

6) Night City Window

7) Night Windows

8) Yellow Sun, Bare Trees

9) Sky Through Trees

10) Cherry Blossom – Grey Sky