My Lover is Killing Me: Trauma and Writing

I lost my mind again. I lose it frequently, to varying degrees, but it generally returns quickly. Lately, though, my mind has taken longer trips, leaving me alone with my body for weeks at a time. In its place, there is rage. I have stared blankly at the ceiling, contemplating suicide. I have pulled my hair, scratched my arms, and slapped myself repeatedly in the face. I have isolated myself. I don’t want to be seen like this.

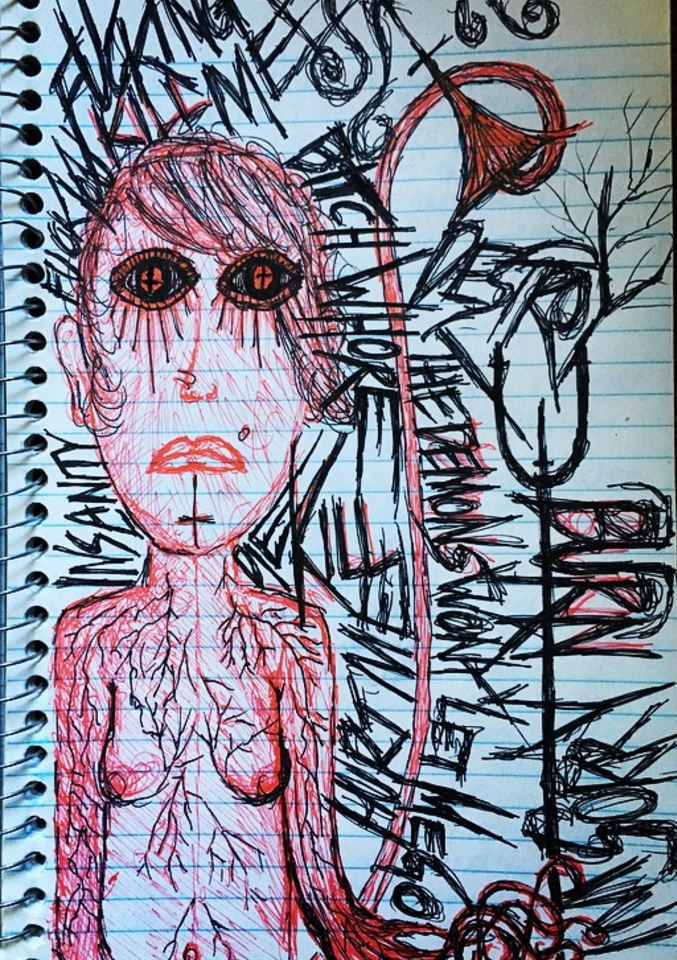

I lost my mind a month ago because I started writing my memoir. I thought enough time had passed— that I was finally strong enough to open my jar of teenage trauma and consume its contents. I read through my old journals, pieced together an outline, and started writing the first draft in a big purple notebook. A few weeks ago, I sat down with that draft and started revising. Every day, the memories intensified. Every day, they pulled me further away from 2017 and closer to 2010, when my body was being touched in dirty motel rooms by dirtier old men. The memories penetrated my dreams, my emotions, and my perception of reality. I began mentally oscillating between my current age and my late teens.

Meanwhile, Trump was gaining momentum in making his devastating promises a reality. Protests broke out across the country. I wanted to rage with my friends, but my internal collapse combined with widespread panic left me petrified and helpless to do anything.

I have post traumatic stress disorder. I’ve felt its effects since I was young, starting with a deadly car accident and then a fire that burnt my childhood house to the ground. It got worse when I was sexually assaulted at 13. It became unbearable when I was robbed and kidnapped five years later. During middle and high school, my pain stayed internal, evident only in my isolation and severe anorexia. After I started drinking and using drugs, though, my approach changed. I turned into the other kind of PTSD sufferer—the kind who acts out instead of caving in. My life past the age of 18 is dotted with extreme incidents of retraumatization in the form of more car wrecks, more rape, and a few years of prostitution.

I play with danger because I’m addicted to adrenaline. Because I don’t know any better. Because chaos is my baseline, my “normal.”

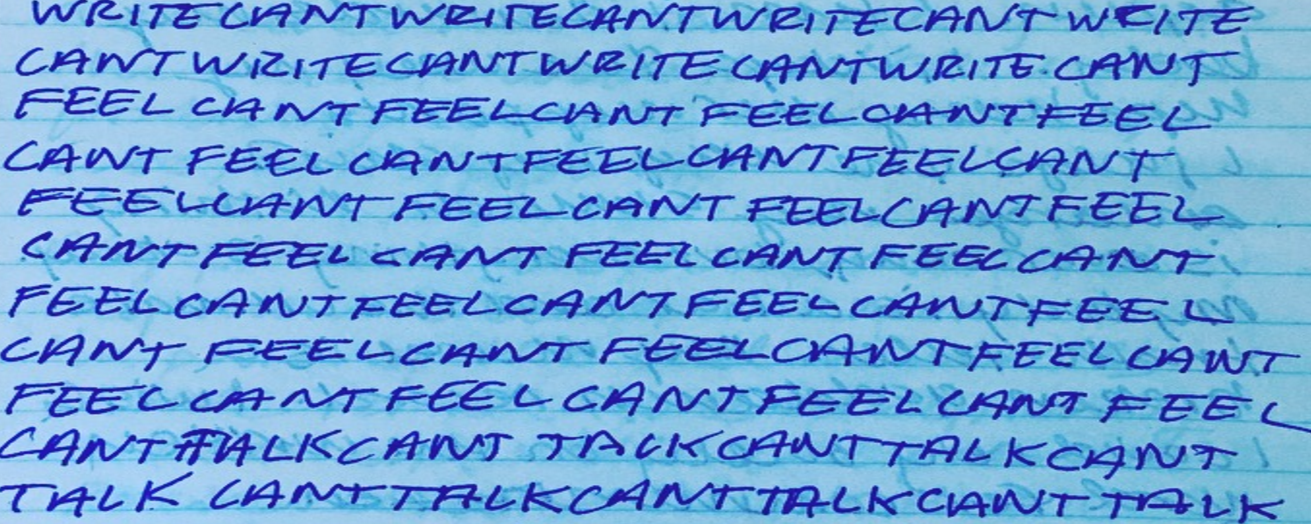

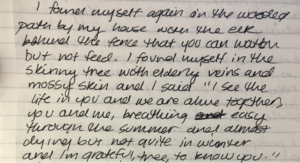

I’ve been writing trauma for almost as long as I’ve lived it. When, at age 12, I was sent to a behavioral health hospital, I started recording my thoughts in a brown journal. It wasn’t my first journal, but it was the first time I admitted to my despair in writing. That journal (as well as two milk crates full of journals that followed) sits beside me now. One entry reads:

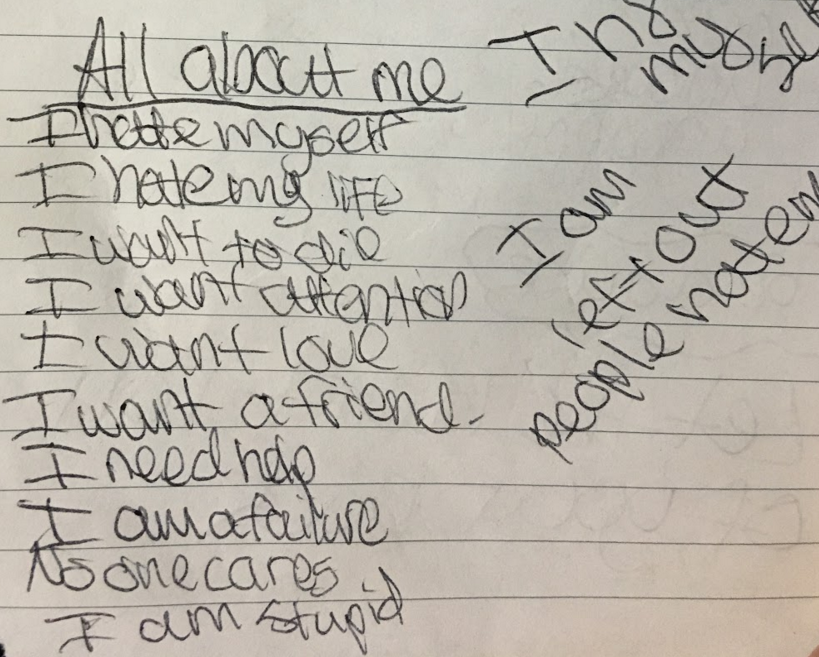

In high school, I turned to another means of expression and started writing lyric-heavy music about insanity, eating disorders, and abuse. My songs were threads connecting the disparate parts of myself. They chipped away the “sane” voice I’d adopted to save face with friends, revealing the self-hatred, terror, and loneliness beneath. By playing these songs publicly, I learned that people could relate. That I wasn’t alone. That my words brought life to experiences that some could not articulate. My playing was sloppy, but when people found solace in my insanity, I found solace in the fact that they felt the same.

I have a compulsive need to be understood—for people to see what I feel so they won’t think I’m crazy. Over the years, I’ve turned to every available means to achieve this. I have thrown fits. I have run from home. I have carved words into my flesh, as though blood were clearer than pen. I have made myself too fat. I have made myself too thin. I’ve used drugs and alcohol to make big messes, desperate for someone to tell me to clean up my act. These approaches have only succeeded in scaring people away from me.

Writing is the single most effective way for me to communicate. It’s the one way I can explain the full extent of my pain without seeming like I need to be institutionalized.

When I was 21, I went to my third treatment center, where I was supposed to get help for PTSD and addiction. I stayed for three months, until the day my roommate hung herself in her closet. I started drinking again. Heavily. I made it two months before hitting another rock bottom and moving back to Minneapolis, where I enrolled in my first memoir class at the University of Minnesota. The professor, a grad student, assigned Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water. It was the only book I read all the way through that semester. Yuknavitch’s candor and fearlessness inspired me to adopt memoir as a primary means of expression.

Our professor gave us a ten-page essay assignment at the end of the semester. I wrote about sex, starting with my early experiences and then tackling the traumatic. Once the pen started moving, it didn’t stop. It took on a life of it’s own. I woke up early every morning and wrote for hours. When it came time to turn in our ten pages, I turned in sixty.

And then I went fucking crazy.

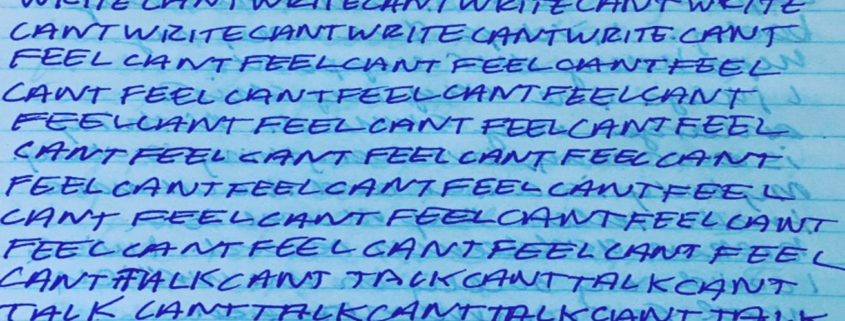

I walked to school every day when I lived in Minneapolis, a two-and-a-half mile trek each way. Each time I crossed the Franklin Avenue Bridge from the West Bank to the East, I thought about jumping into the Mississippi River. I was stuck inside my trauma—not just one of them, but all of my traumas at once. I was walking through a constant flashback that wouldn’t turn off. I started self-harming again, partially in an attempt to bring myself back to reality, but also to apply punishment for being “dirty.” I dissociated almost every night, usually to the point that I couldn’t talk. I would try, but my lips wouldn’t open. My mouth was stitched shut. The words got stuck in the back of my throat and wouldn’t budge.

Meanwhile, the people who loved me and knew what was going on begged me to stop writing. I insisted that I couldn’t. I had a mystery to solve and misery to wallow in, so I kept going, kept pushing, kept forcing the memories that wanted to stay hidden onto the page. And I went too far. My body and brain shut down on me. I collapsed into months of midday naps and zero writing. The unavoidable recovery period was long and painful. I missed my toxic lover. I missed my writing.

This is my constant battle: Should I write this thing? Should I stop? Is this doing me harm or good? I’ve come back to the same answer again and again: It’s helping and it’s hurting, but, for better or worse, I’m stuck with it. No matter where or how well I hide, writing always finds me.

* * *

I retraumatize myself with my writing all the time, especially when I share it publicly. It’s like compulsively stripping naked in front of fully-dressed crowds on a daily basis. Writing is one-sided: you’re the vulnerable party and everyone else is free to dismiss or scold or piss on your words. People often read my writing (my personal blog especially) and decide they know me intimately, that they can describe me succinctly and tell me how to deal with myself. Other people read my writing and call me a slut, a crazy bitch, a liar.

So if writing about trauma is traumatizing and sharing it is traumatizing, why the hell do I do it?

Because writing is multifaceted. Every time I try to find its fundamental purpose, I come up with something different. I write for every reason. I write for no reason. I write because it’s compulsive, addictive, automatic. I write for the chemicals—to trigger action in my amygdala. I write to heal and self-harm. I write to build connective tissue between my separate selves. I write because I don’t understand. I write because I do. I write as proof and testimony. Writing mends, writing breaks, writing is a daily cycle of shattering myself and rearranging the pieces. Writing makes manifest my inner world. Writing is my child—my little girl. And she has different moods on different days. Sometimes she throws tantrums. Sometimes she enlists as a keyboard warrior. Sometimes she types vicious things to old friends turned enemies. She’s an unruly child, but her heart is good.

I have to listen to my body when it comes to writing—to accept that when I’m ready to write something, it will emerge (mostly) organically. I know it’s not time to write when my body and mind and memories scream, “No, not now. This fire is too hot.”

I do write most days, but I don’t fault myself if I skip a few. Five years after my first attempt at memoir, I’m finally attending to my limitations, figuring out where I need to draw the line before I fall too far. If my body says, “Get the fuck away from this essay,” I listen. I put down the pen and take a walk or watch funny monkey compilations on YouTube. Sometimes I need a week away from trauma writing, sometimes a month. When I pace myself, I don’t need nearly as much recovery time.

Last summer, Antioch professor Christine Hale suggested that I begin recording positive memories that can anchor me throughout my writing process, so that the traumas don’t swallow me whole. I’ve tried to make a habit of this, jotting down notes about my dog, black-eyed Susans, Christmas ornaments, and a seagull friend I made by the Atlantic Ocean. It helps, even though positivity is still mostly foreign to me.

When I get to a point where my body says, “Step back from this,” I try to spend a week writing only these light-filled memories. When enough time has passed and I feel ready to return to the trauma writing, I weave some of the positive memories I’ve accumulated throughout whatever I’m working on. The goal is to give myself—and my readers—a few seconds to breathe.

When I get to a point where my body says, “Step back from this,” I try to spend a week writing only these light-filled memories. When enough time has passed and I feel ready to return to the trauma writing, I weave some of the positive memories I’ve accumulated throughout whatever I’m working on. The goal is to give myself—and my readers—a few seconds to breathe.

* * *

But what can I do now, in the midst of this collective political trauma? This is trauma I can’t avoid unless I turn off the news, throw out my phone, and delete my social media accounts. Even then, it’s inescapable. Trump’s rise has encouraged men like that 30-something white guy in the BMW to call my boyfriend a “faggot” and a “homeless piece of shit.” It’s why a Trump supporter at the gym felt entitled to say, “Just lie back and spread your legs,” to my mother. Now we have the trauma of watching and reading about deportations, blatant racism, and the promise of a border wall. There’s the trauma of knowing that my friends are being targeted, that my body is being targeted, that many more will be targeted, too. I’m on edge. I feel it in my stomach, my limbs, and my chest.

How do I balance self-care with care for my fellow humans? How do I participate without compromising my safety and mental health? How do I make space for myself when so many people around me are suffering?

My current solution is to stay close to home and take care of those around me—my friends, my partner, my dogs, my family, and anyone who happens to cross my path. Beyond that, I’m still doing what I know how to do, which is to write about insanity, addiction, prostitution, and PTSD. Those are the things I’ve lived and areas in which I have something to give. Right now, I can write for my fellow trauma survivors, reminding them they’re never alone and creating a platform for them to be vulnerable.

If I push past my limits and live in a constant state of hyperarousal—which many of us are right now—I will eventually collapse. The fight will be stripped from me. I have to listen to my limits. I know that I am not my strongest self right now and that I can’t participate in the same ways that other people do. I haven’t been to a protest. I had to remove myself from Facebook. I can’t watch much news. It’s embarrassing to admit, but it’s my truth.

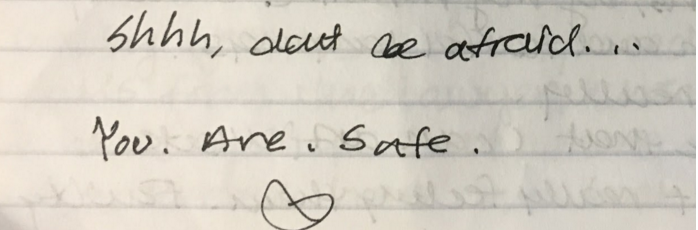

To stay in fighting shape, I take time to disconnect and breathe. I hike deep in the forest and talk to the trees. I sit by the tracks and watch freight trains pass. I collect rocks and feathers and fox teeth.

I write the light, write the pain, and return to the light again.

Emily Eveland a.k.a. Leif E. Greenz, is an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in xoJane, Narratively, City Pages, The Minnesota Daily, and Entropy. She shares far too much information about her mental health and sex life on her blog, Big Mouth.

Emily Eveland a.k.a. Leif E. Greenz, is an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in xoJane, Narratively, City Pages, The Minnesota Daily, and Entropy. She shares far too much information about her mental health and sex life on her blog, Big Mouth.