Making Art from the Everyday

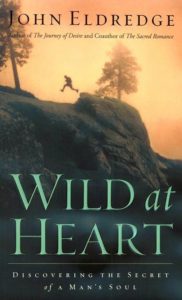

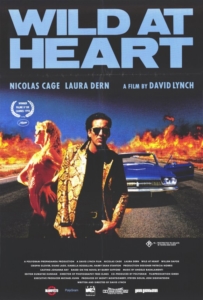

When I was sixteen I read a Christian men’s book called Wild At Heart: Discovering the Secret of a Man’s Soul. The book was about how to unleash the inner William Wallace (from the film Braveheart), and live a life of adventure and danger (within, of course, the bounds of traditional gender roles and conservative, evangelical Christianity). It pains me to remember reading this book. It is both embarrassing to remember what kind of person I was—an awkward teenager growing up within the church—and also achingly nostalgic, because I was a young man full of hopes, dreams, and ambitions. As a result of reading the book, I thought my life was supposed to resemble that of the male archetype hero from Hollywood movies. As I grew older, I became frustrated by the mismatch with reality. This Wild at Heart book set up a dichotomy for me that I spent the next twelve years of my life trying to understand: one, ultimately, about expectations.

What if your life isn’t like Mel Gibson’s William Wallace or Russell Crowe’s Maximus from Gladiator? What if, instead of stampeding down the green fields of Sterling or overthrowing the Roman Emperor, you were simply worried about pimples in the mirror and boners in math class? And what if, as you got older, you saw that life was not filled with epic battles or daring romances or high-speed car chases, but with trips to the grocery store and lines at the bank, and doing the dishes, and fighting with your partner?

What if your life isn’t like Mel Gibson’s William Wallace or Russell Crowe’s Maximus from Gladiator? What if, instead of stampeding down the green fields of Sterling or overthrowing the Roman Emperor, you were simply worried about pimples in the mirror and boners in math class? And what if, as you got older, you saw that life was not filled with epic battles or daring romances or high-speed car chases, but with trips to the grocery store and lines at the bank, and doing the dishes, and fighting with your partner?

What do you do with these two disparate visions of reality?

For Americans, around 30% of our lives are spent working, and another 33% sleeping. For the average person, that leaves only 37% left: for fun, leisure, art, exercise, social obligations, parenting obligations, yard work, and (if you’re William Wallace) fighting for independence from England.

The great tragedy of adulthood is in realizing that your once-imagined epic life is basically reduced to “making it” or “surviving.” Call it a fallout of the advertising of the American Dream.

The great tragedy of adulthood is in realizing that your once-imagined epic life is basically reduced to “making it” or “surviving.” Call it a fallout of the advertising of the American Dream.

The conceit of Wild at Heart is not unique. It’s not found only in the self-help or Christian-living sections of the bookstore; it exists all over our culture, from movies and magazines to TV and social media. We fantasize a sort of life that is nowhere near the reality. No one wants to think, post, or brag about what’s going in our lives in those moments of sleeping, working, emailing, driving, and so forth. If movies used to reflect reality, now reality seems more recognizable if it resembles the movies.

Perhaps this is an issue better worked out in a therapist’s office. Still, this whole thing has me really, really, bothered. Maybe it’s my lapsed religious upbringing, or what I didn’t learn as a young man that a young David Foster Wallace learns in his book, The Pale King:

. . . that life owes you nothing; that suffering takes many forms; that no one will ever care for you as your mother did; that the human heart is a chump . . . that the world of men as it exists today is a bureaucracy. This is an obvious truth, of course, though it is also one the ignorance of which causes great suffering.

I’ll always love epic adventures. I’ll be a Lord of the Rings fan and can watch Game of Thrones until The Mountain bursts my eyes out, but what interests me lately is art or writing that deals not with the fantastical, the projected, and pseudo-self-help, but with how to navigate the trenches of daily, monotonous, real life. The authors and artists I love now are ones who elevate the banal elements of life to something sublime and beautiful. One such author is Karl Ove Knausgaard.

Art often exists on a spectrum between imitation and imagination, between realism and idealism. For some, art is mimesis, the imitation of reality. A painting of a lake. A portrait of a person. But for others, art is a launching pad for the undiscovered: a distant planet, a magical world, the Marvel/DC Universe.

Most of what one might call traditional narrative structure involves a synthesis of imitation and imagination. Many films show improbable events played out in everyday life through largely manipulated and idealized scenarios, depicting only the most dramatic events of the narrative. This makes sense, because to be compelling, stories need drama, action, resolution, and so on. As writer and MFA mentor Peter Selgin recently said about plot, “You cannot dramatize the routine.” But my frustration remains, because the majority of life is routine. I believe Selgin would readily admit there are exceptions to his rule: Routine can be made compelling by those willing to take the plunge. But you have to dive deep.

Enter Karl Over Knausgaard. He’s the latest writer to plumb the minutiae of human experience. Comprised of six volumes, his book, My Struggle (Min Kamp, in the original Norwegian), is a novel with tremendous scope, almost as daunting as Marcel Proust’s classic seven-volume novel, In Search of Lost Time. What Knausgaard does very well is to observe and replicate the tension and anxiety in everyday events. His perspicacity for detail and ability to pay attention to the habitual or quotidian events unfolding around him, combined with an aptitude for creating suspense and anxiety, make him fascinating to read.

This is the central set-up: Knausgaard wants to do something heroic and has within him the “ambition to write something exceptional one day,” but finds himself too embroiled within the tasks of everyday (i.e., cleaning, cooking, taking care of his children, etc.) to do anything about it. But what keeps us reading is Knausgaard’s attention to detail, his ability to take us alongside him in his awareness.

The sentence structure and imagery of Knausgaard’s writing do not quite have the richness of Nabokov. He is not as elaborate as Proust or Woolf. However, he writes wonderful observations with astute detail choice. And the details are not few and far between: they are what constitute the entirety of My Struggle. You could call the work (or Knausgaard himself) self-involved, pretentious, and navel-gazing, however the writing itself is none of these things. It is simple, elegant, non-pretentious prose.

Because of the length of My Struggle and the overall tone and observations Knausgaard builds over pages, it’s difficult to quote passages. His observational detail, and slow, tense writing cannot be succinctly parsed. The mood and length lend extra gravitas. Multiple pages are spent on the quest to smuggle beer to a party in high school; nearly two hundred pages on the four to five days after his father’s death.

It is the job of the writer to pay attention. What sets Knausgaard apart is his eye for detail on the ordinary alongside the extraordinary. His writerly observations equally focus on the big themes of death, love, family, and anxiety, as on forests, crossing a street, riding in a car, or toilets. He pays as much meticulous attention to death and marriage as he does to cleaning, cooking, and walks through various landscapes.

It’s these observational details applied to crude, everyday, banal, adolescent actions that make My Struggle intriguing. For me, through Knausgaard, I’ve found this to be the solution to my question of how to make art out of the everyday: simple awareness. The catch? That true, empathetic, and lucid awareness is not really simple. It takes a lot of freaking effort.

I am older now and my expectations are lower. I’ve spent the last decade struggling to figure out how to appropriately set my own expectations of life. I often wonder how much of my earlier expectations were learned through my religious upbringing, or if they came naturally from my own sense of romanticism and ambition. Who knows. We humans are complex conglomerations of influence, personality, and upbringing. So this is what interests me now: exploring this complication inherent within all of us—and sometimes I am just as excited by this prospect of self-inquiry as I am by any kind of heroic battle.

Levi Rogers is a writer and coffee roaster out of Salt Lake City, UT. He lives with his wife Cat, his dog Amelie, and his many socks, all of which have holes. He’s currently an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles.