Middle School is for Monsters

all names and identifying data have been changed to protect privacy

My friend Rebecca and I, both writers, have been invited to lead a creative writing and empowerment group for girls at a local middle school. Our own adolescence is a distant country, but we both remember discovering our writing, our creative process, at that age. Since then, writing has been a life raft. We’re excited to have the chance to pass it on.

“I can’t remember,” Rebecca says while we are brainstorming and preparing for the group, “do eighth grade girls want to be children or adults?”

“Both,” I say. “That’s the problem.”

We plan to use creative writing to give the girls a place to work through this middle space between childhood and adulthood. Our hope is to create a comfortable space where they can explore identity through play; where they can connect rather than perform. During the middle school years, the tectonic plates of identity shift, and like the earth after a quake, the girls will find themselves changed on the other side. If they’re lucky, they’ll come out of it with a solid sense of themselves. The luckiest will also land with a real friend or two who can still see them beneath the armor of adulthood. Connection equals sanity.

We arrive on our first day armed to teach with the words of Lynda Barry and Climbing PoeTree to inspire us, and with composition books and cheese sticks. We are ready.

* * *

The group meets during the girls’ lunch period in a large, fluorescent-lit classroom that we shrink by pulling metal folding chairs into the center of the room. We place a pile of decorated composition books in the middle, for the girls to choose from. And, of course, we provide food: cheese and crackers, strawberries, juice boxes. On the first day, the girls file in one by one. I wouldn’t be able to guess their age if I saw them on the street. They could be sixteen; they could be twelve. We anticipated that it might be challenging for them to feel comfortable at first, but we were wrong—there’s no easing into the hard stuff with these girls. It’s as if they’ve been waiting for the release valve.

On day one, as an icebreaker, we ask the girls to tell us a story about themselves that we might not have guessed. Elena, who recently transferred from a different school, describes a time when her previous school was put on lockdown due to a threat of violence. Her eyes are downcast as she tells us her story; her voice is hushed. She tells us the kids weren’t allowed to leave their classrooms and no one explained what was going on. They were told to be quiet and work on their homework, but Elena says that she felt confused, and scared. Meanwhile, Dani, on the other side of the circle, folds her arms across her chest and sinks a little deeper into her chair. She wouldn’t be upset if that happened to her, she says. She wouldn’t be scared at all. Several of the other girls nod. None of them would be scared. Apparently, in middle school, being scared is not an option.

The girls in our group claim a diverse array of identities, but by virtue of living in female-identified bodies, they are all charged with similar developmental/psychological tasks. In one way or another, they are asking themselves and each other: How do I learn to trust others and accept myself? How can I comfortably and proudly express my identity? How do I live strong in a female body in this world?

* * *

“Is this good? Does this suck?” — Lynda Barry, What It Is

Lynda Barry, graphic artist, writer, and all around creativity goddess, reminds us that we are born to create and play. But somewhere along the way, we forget how. We begin to want to tell the correct stories, to draw well. We strive to produce what we imagine other people want to see. Performance nudges out creativity. If play is our birthright and our communion, the space where we share our innermost, mysterious, unspoken selves with our fellow humans, then we’re at a loss from a very young age.

Where do we get the idea that we aren’t supposed to play anymore? Should we blame middle school? Or can we use this developmental precipice as a place to create connection and empower? As writers, Rebecca and I know that play is essential to our humanity, to our psychological survival. Can we use play, creativity, to arm these girls for the travails of early adolescence in this particular moment in our history?

* * *

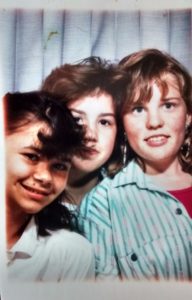

The author and friends in eighth grade

When I was in seventh grade, I spent hours playing dolls with my best friend Jenny. Our Barbies were untamed. We intentionally wilded up their hair and they frequently went topless. When Ken kidnapped Skipper and whisked her under the dining room table in a plastic sports car, my old Wonder Woman doll, a head taller than the rest, led the rescue wearing nothing but a belt of Christmas bells around her waist. As we played with our Barbies, a secret and powerful space unfolded, a space where we could use play to grapple with the mysterious changes that were unfolding within our own bodies. Hair. Blood. Mounds of rising flesh. Sensations we didn’t understand. The ogling eyes and odd comments from men and high school boys. The Barbies gave us a place to work it out.

Until we realized we weren’t supposed to play anymore. Of course I don’t play with Barbies! I heard myself saying at school. That was in eighth grade. Later that year, I was called up in front of the entire middle and high school at an assembly. I overheard a group of high school boys talking about me as I walked up to the stage. Is that Melissa? When did she grow tits?

Jenny and I soon tucked the Barbies away in their little plastic boxes, stuffed them in the back of the closet. Wonder Woman too. Girls were being shoved into the wall in the hallway of our middle school, taunted if they hadn’t started shaving. Shave your legs or become a social pariah. Playtime was over. It was time to perform.

* * *

A few weeks in, Rebecca and I introduce Lynda Barry’s “Monster Jam,” a cartooning activity, to the girls in our writing group. In this activity, participants have five minutes to turn a shape into a monster. The exercise is timed, so there’s not much room for perfectionism and self-critique. At first we have to re-direct the girls as they sigh and cross things out.

Sample Monster Jam

“Keep going,” we say. “It doesn’t have to be pretty. It doesn’t have to be perfect. It’s a monster.” The fact that we are making monsters gives everyone permission to be wild, to be silly, to play. Soon, the giggling and the muttered critiquing subside and the circle of girls becomes seven points of distilled concentration, each face flickering with quiet delight as we give them additional prompts, challenging them to give the monsters parents, siblings, favorite toys, true loves, and best friends. The act of cartooning and creating, once fraught with perfectionism, becomes delightful. In the weeks that follow, the girls draw several cartoons of their monsters, write stories about them, discuss their dilemmas in impassioned detail, turning over possible solutions to their problems.

Once the impulse to critique is stripped away, the monsters become the proxy, the self, living in a space of play. Like my old Barbies, they are a half-space removed from reality. They give the girls the space they need, the me/not me, to find clarity and connection, just as Rebecca and I, in adulthood, have learned to use writing to make sense of our lives and our world. The psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott described play, creativity, as a potential space: “…it is play that is the universal, and that belongs to health: playing facilitates growth and therefore health.”

* * *

Three of the girls in our writing group recently transferred from other schools. It’s week five when Cora tears up during the closing ritual at the end of the hour we spend together. “I feel so homesick,” she says, a tear sliding down the side of her nose. “I don’t know if I’ll ever find a place where I belong.”

Dani, who at the beginning of our group spent much of her time with her arms folded across her chest defensively, speaks up. “This is a safe space,” she says. “That’s why we’re here together. You can be anything you want to be. You won’t be judged.”

Rebecca and I catch each other’s eyes. The monsters are working their magic. Play spills into reality, opens space for community, creates a shift, a connection, a change.

* * *

The last day the group meets happens to be the Thursday after Election Day. The man about to ascend to the United States presidency is the adult embodiment of the boys who pushed us to the wall, the men and boys who have scrutinized our bodies with forensic efficiency for most of our lives. One by one, the girls file in. Rebecca and I have dimmed the fluorescent lights and made our circle of chairs, but today, the air in the room feels flat, deflated. The girls take their seats, and Amy, who has only recently begun to eat lunch in front of the group, puts her feet up on a second chair, then pulls back, apologizing for taking up so much space.

“Wait a minute,” says Rebecca. “Let’s all take up as much space as we can.”

Several of the girls laugh. Typically, they’re not supposed to put their feet up on chairs during school. But in this moment, spreading out, greedily taking up as much space as we can, feels necessary, important. Rebecca and I join the girls in pulling second chairs into the center of the room. During our last group, we all use two chairs. We put our feet up. We drape our arms dramatically over the seat backs. We talk about power poses, stand up and make triangles with our elbows, hands on our hips. In my heart, my Wonder Woman doll climbs back out of her box and, surrounded by powerful young women and a dear friend, I invite her back into my body. As the session comes to a close, several of the girls want to make a circle together. We come together at the center of the room, stand shoulder to shoulder. The girls tell us they’ve taken their monster books home; they’re still writing in them. A few say they wish the group could go on. We remind them that they’ll still be together in school, every day, that the connection we’ve made here leaves the room with them. Then we separate, go back out into the rest of our lives—a creative, imperfect, empowered community of women, bringing our wonder out into the world where, whether you like it or not, we will take up lots of space. We will be seen. We will be heard. And Rebecca and I, just like the girls, are different now. The part of us that was pushed against the wall many years ago pushes back.

“You

who replants today despite unwelcoming soil

so tomorrow can be worthy of the roots;

Your children will grow up to be oak trees”

Alixa Garcia

Melissa Benton Barker is an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. A Navy brat and native of nowhere, she currently lives in a small Midwestern town where she spends her time imagining stories, wandering in the woods, and raising children-sometimes simultaneously! Her work appears or is forthcoming in the Manifest-station, Smokelong Quarterly, and Literary Mama. She serves as Lead Fiction Editor at Lunch Ticket.

Melissa Benton Barker is an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles. A Navy brat and native of nowhere, she currently lives in a small Midwestern town where she spends her time imagining stories, wandering in the woods, and raising children-sometimes simultaneously! Her work appears or is forthcoming in the Manifest-station, Smokelong Quarterly, and Literary Mama. She serves as Lead Fiction Editor at Lunch Ticket.