Mommy, What if It’s Terrorists?

Fireworks from the beach along the La Promenade des Anglais

French National Day commemorates the July 14, 1789 storming of the Bastille by a mob of enraged Parisians looking for ammunition in the fortress-prison that symbolized the tyrannical Bourbon monarchy. The Bastille’s fall marks the beginning of the French Revolution. On Bastille Day this year, Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel drove a nineteen-ton white Renault truck into crowds gathered for a fireworks display, killing more than eighty people and injuring, at least, another three hundred. It was the eighty-seventh terrorist attack world-wide since the beginning of the month.

Let that sink in. Eighty-seven counts of terrorism before mid-month. By the time Bouhlel breached barriers that were erected on the Promenade des Anglais to create a pedestrian-only area for viewing the celebratory fireworks and plowed into the throng, there had been more terrorist attacks than occurred in all of 2001, the year when President George W. Bush declared a global war on terror in response to the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

UA Flight #175 approaches the South Tower

My younger son, Parker, not yet six months old on 9/11, slept through the early morning hours as al-Qaeda militants hijacked American planes and piloted them toward the World Trade Center in New York City. He was still asleep as the sun rose in Southern California when Peter Hansen, a passenger on hijacked United Airlines flight #175, called his father.

“It’s getting bad, Dad. A stewardess was stabbed. They seem to have knives and Mace. They said they have a bomb…I don’t think the pilot is flying the plane. I think we are going down. I think they intend to go to Chicago or someplace and fly into a building. Don’t worry, Dad. If it happens, it’ll be very fast.”

Three minutes later, along with Hansen’s father and millions of others worldwide, I watched live on CNN as Los Angeles-bound United Airlines flight #175 crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center.

I prayed that day. Stunned, more grief-stricken than afraid, it was the only thing I could do.

* * *

What, if any role, do writers have as observers of and participants in diffuse wars like the War on Terror? In addition to military action, diffuse wars include guerrilla strategies and tactics, as well as a multiplicity of political measures, designed as much to placate as to protect the public. Think Cold War-era bomb shelters and civil defense training to contemporary airport security screening and domestic surveillance schemes.

The destruction and chaos of war has proved to be a potent catalyst for writing as a creative act that is culturally valuable because it helps us to understand the world. According to Kate McLoughlin, acclaimed for her study, Authoring War: The Literary Representation of War from the Iliad to Iraq, war writing “warns against pursuing armed conflict, exposes its atrocities, and argues for peace. It records the acts of war with as much accuracy as is possible, and it memorializes the dead. It is voyeuristic, exploitative, and sadistic; it is also tender, selfless, and comforting. It is gleeful and angry; inflammatory and cathartic; propagandist, passionate, and clinical. It is funny and sad.” Stephen Crane’s war novel Red Badge of Courage tells the story of Henry Fleming, a young Civil War soldier, who grapples with the choice between self-preservation or self-sacrifice in battle. Paul Bäumer, the protagonist in Erich Maria Remarque’s novel All Quiet on the Western Front, asks this question of his “lost” generation following World War I: What was worth the deaths of eight million men?

Regarding the current century, author and Iraq War veteran Matt Gallagher’s search for the “great novel about the War on Terror” yielded mostly memoirs, press accounts, and personal testimonies. Perhaps this result is appropriate. Author Graham Swift opined that today’s 24/7 media stream of news and commentary makes journalists and other nonfiction writers the best source of information and social support.

I’m not so sure.

* * *

Nearly a decade after the September 11 attacks, Parker found a tiny video card on the sidewalk outside of our local Rubio’s restaurant. He wanted to keep it. Before I could articulate my first thought, “Sure you can…,” his envious big brother yelled, “Drop it!”

“No!” Parker screamed. He wrapped his fingers around the tiny bit of 21st-century technology, and dug in for a fight.

“Take it into Rubio’s, in case someone comes looking for it,” I said. I hoped this suggestion would forestall a sibling brawl.

“No!”

“Parker, just put it down,” I said. “Why do you want it so badly, anyway?”

“I have to see what’s on it.”

“Who cares? It’s not yours…”

“Mommy, what if it’s terrorists? What if they left it for someone? What if they’re planning an attack?”

Whoa! I thought. Dumbstruck silent rather than wise, I did not laugh.

“Parker, just put it down. I don’t think the card has anything to do with terrorists. Someone just dropped it.”

Makeshift Memorial, San Bernardino, CA

The idea of terrorists targeting anywhere in Inland Southern California seemed ludicrous at the time. The region does have plenty of hotels, shopping centers, places of worship, transportation hubs and corridors, and schools, all of which make prime targets due to their potential for large numbers of people to congregate. But locations in Riverside and San Bernardino counties are nowhere near as likely as those in Los Angeles or San Diego to draw the media’s attention and the sizable audience that terrorists desire.

Yet, in December 2015, Syed Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik attacked an office holiday party at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino, where Farook worked. They killed fourteen people, and injured twenty-two.

* * *

Mommy, what if it’s terrorists?

* * *

Fear is chief among children’s psychosocial responses to terrorist activity—whether that exposure is due to media, overheard adult conversations, or physical proximity. Any assurance that terrorism is not an existential threat to the nation simply cannot trump fear of attack and a deep-seated desire for protection. Yet, results of a recent Wall Street Journal poll indicate it’s Americans over thirty-five, those who were children during the Cold War, that fear terrorist attacks most. The way adults experience vulnerability to terrorism today is arguably related to how well they managed war-related distress as children. In contrast to the unpredictability of terrorists’ behavior, the social construction of the Cold War in books and films, as well as in the news media and history texts, contained the Soviets within clearly-defined and heavily armed borders.

Children during the first decades of the Cold War could rely on Captain America, Ironman and other heroes for protection. When novelist and nature writer Brenda Peterson ducked and covered under her school desk in Virginia during the 1960s-era civil defense drills, for instance, she imagined R. Tyranno would grab the bomb and “hold it high until he could defuse it with his amazingly agile hands”; Brontosaurus would bend over her, “a gentle bodyguard against shattering glass”; and Iki would “offer her dorsal fin and speed off to safety” (118).

By the Cold War’s final decade, the size, location, and targets of U.S. and Soviet nuclear arsenals were common knowledge and Americans were optimistic about superpower cooperation to reduce nuclear arsenals and support democratic elections in Eastern Europe. As a result, children generally understood that nuclear war was more likely to result from some accident than from rational action, though fiction and films marketed in the 1980s made it clear that life for those who survived a nuclear attack would be perilous. Journalist Chris Lites characterized The Day After, the top-ranked film about two Midwestern towns following a nuclear war, as “terrifying.”

Jennifer Gray in Red Dawn

It never occurred to me as a child that the USSR might attack my Southern California “backyard.” With the exception of the Soviets’ invasion of Colorado in Red Dawn, a violent cult film based on Kevin Reynolds’ Ten Soldiers, the era’s bad guys stayed conveniently outside of the United States, and would be easily identified anyway–by their bulky coats, Russian fur hats, and heavy accents. In contrast, Millennials, and members of the so-called “Homeland” generation that follows, never experienced an environment over which they felt control. As adults, they are inured to the anxiety associated with the unpredictability of attacks by organized terrorists and “lone wolf” radicals.

* * *

Responding to the dearth of literature about the War on Terror, young adult novelist Alan Gibbons suggested that it’s just too soon. Literature about the world’s great conflicts—from A Tale of Two Cities and War and Peace to Oscar and Lucinda, March, and All the Light We Cannot See—has been written long after they occurred. Alternatively, it’s possible that too few people have been directly involved in the War on Terror compared with conventional wars of comparable scale. World War II involved nearly two billion combatants and was responsible for as many as eighty million deaths, including soldiers, civilians, and those who died from disease or starvation. Though data on the War on Terror remain incomplete, we do know that more than two and a half million U.S. and British troops served in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq; including casualties from terrorist attacks, at least two million people worldwide have died. Surely millions are enough.

Finally, perhaps the War on Terror, which includes distinct military actions in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as many hundreds of terrorists acts and related conflicts globally, is too big for a single voice to capture. The trickle of fiction and literary nonfiction amid the tide of more immediate, informational prose supports this explanation.

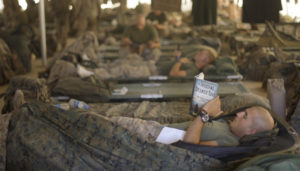

Reading in Iraq

Notable literature on the War on Terror includes Roy Scranton’s “War and the City” series in The New York Times, short story collections such as Fire and Forget: Short Stories from the Long War, Redeployment, and The Corpse Exhibition: And other Stories of Iraq, Jonathan Foer’s experimental Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, and the The Yellow Birds, Kevin Powers’ haunting war parable. Much of the work that appears on recent lists of contemporary war writing is less well known and does not yet capture the enormity our individual and collective experiences of the War on Terror. Those who endeavor to remedy this situation might begin by reading the literature that does exist, as well as the broader body of work on terrorism, which includes Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent and Don Delillo’s Mao II.

This relatively small yet wide-ranging body of work provides exemplars of what writers of war and terror ideally strive to achieve: historical accuracy and truthful interpretation. Beyond that, they approach narrative, characters, and relevant historical contexts in their own ways. The September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center are central to Extremely Close and Incredibly Loud, much as the “Luddites are important part to the backdrop for Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley. The war in Afghanistan provides context for Trent Reedy’s young adult novel, Words in the Dust, like the Napoleonic Wars inform the milieu of Jane Austen’s novels.

* * *

Flight #175 crashing into the World Trade Center felt like an unexpected punch to the gut. Breathless and unable to speak, my mind sought comfort in long forgotten verse. Do not fear, for I am with you. I felt there was nothing more I could do. Terrorist attacks have ceased to shock me. I was saddened by the appearance of Bouhlel’s attack in Facebook newsfeed, disgusted even, but not speechless. I remembered Parker asking, “Mommy, what if it’s terrorists?” and I began to write.

Reading List:

Blasim, Hassan. 2014. The Corpse Exhibition: And other Stories of Iraq. Penguin.

Brooks, Geraldine. 2006. March. Penguin.

Brontë, Charlotte. 2006. Shirley. Penguin.

Carey, Peter. 1997. Oscar and Lucinda. Knopf Doubleday.

Crane, Stephen. 2007. Red Badge of Courage. Norton.

Conrad, Joseph. 2007. The Secret Agent. Barnes and Noble.

Dickens, Charles. 1998. A Tale of Two Cities. Dover.

Delillo, Don. 1992. Mao II. Penguin.

Doerr, Anthony. 2014. All the Light We Cannot See. Scribner.

Foer, Jonathan. Extremely Close and Incredibly Loud.

Klay, Phil. 2014. Redeployment. Penguin.

McLoughlin,Kate. 2014. Authoring War: The Literary Representation of War from the Iliad to Iraq. Cambridge.

Peterson, Brenda. 1991. Nature and Other Mothers. Ballantine.

Powers, Kevin. 2014. The Yellow Birds. Back Bay Books.

Reedy, Trent. 2013. Words in the Dust. Scholastic.

Remarque, Erich Maria. 1987. All Quiet on the Western Front. Ballantine.

Scranton, Roy. 2013. Fire and Forget: Short Stories from the Long War. Da Capo.

Tolstoy, Leo. 2008. War and Peace. Vintage.

Juliann Allison is a feminist scholar, environmentalist, homeschool advocate, yogini, runner, rockclimber, mate, and mother of four with a passion for the outdoors. She is Associate Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies and Public Policy at UC Riverside, and an MFA student at Antioch University Los Angeles.