Five Poems by Murilo Mendes

FIRST COMMUNION

I never had such a summer day

boys flying kites

far-off sounds of flutes

brisk bells in the sun

the world head-over-heels

aspiring to joy:

And me shivering sadly

in my velvet clothes

feeling nothing of true presence.

PRÉ-HISTÓRIA

Mamãe vestida de rendas

Tocava piano no caos.

Uma noite abriu as asas

Cansada de tanto som,

Equilibrou-se no azul,

De tonta não mais olhou

Para mim, para ninguém:

Cai no álbum de retratos.

PREHISTORY

Mom dressed in lace

played piano in the chaos.

One night, weary of noise,

she spread her wings,

poised herself in the sky,

and in a daze lost sight

of me and everyone else:

she fell into my scrapbook.

ESTRELAS

Há estrelas brancas, azuis, verdes, vermelhas.

Há estrelas-peixes, estrelas-pianos, estrelas-meninas,

Estrelas-voadoras, estrelas-flores, estrelas-sabiás.

Há estrelas que veem, que ouvem,

Outras surdas e outras cegas.

Há muito mais estrelas que máquinas, burgueses e operários:

Quase que só há estrelas.

STARS

There are white, blue, green, and red stars.

There are fish stars, piano stars, girl stars,

whizzing stars, flower stars, thrush stars.

There are stars that see and hear,

some are deaf and others blind.

There are many more stars than machines, bourgeois and workers:

Almost all there is, is stars.

A MULHER DO DESERTO

A mulher de areia

Penteia os cabelos de folhas de palmeira,

Estende as mãos de cardo

Pedindo água,

Depois descansa as mãos de cardo

Na humildade da pedra.

A mulher do deserto

Pensa nos seus amores infelizes,

Pensa nos seus amores

Que se evaporam quando o sol nasceu.

Depois não pode mais pensar

Porque o tempo é pouco para pedir água.

THE DESERT WOMAN

The sand woman

combs her palm-leaf hair

stretching out her thistly hands

to beg for water,

then rests her thistly hands

on the poverty of a stone.

The desert woman

thinks of her unhappy loves,

she thinks of her loves

that evaporate with the sunrise.

Then she can’t think anymore

because time’s short when begging for water.

SALMO Nº 3

Eu te proclamo grande, admirável,

Não porque fizeste o sol para presidir o dia

E as estrelas para presidirem a noite;

Não porque fizeste a terra e tudo que se contém nela,

Frutos do campo, flores, cinemas e locomotivas;

Não porque fizeste o mar e tudo que se contém nele,

Seus animais, suas plantas, seus submarinos, suas sereias:

Eu te proclamo grande e admirável eternamente

Porque te fazes minúsculo na eucaristia,

Tanto assim que qualquer um, mesmo frágil, te contém.

PSALM No. 3

I proclaim you wonderful, admirable,

not because you made the sun to rule the day

and stars to rule the night;

not because you made the earth and everything in it,

the fruits of the field, flowers, cinemas and locomotives;

not because you made the sea and all it contains,

its animals, its plants, its submarines, and its mermaids:

I proclaim you wonderful and eternally admirable

because you make yourself tiny in the Eucharist,

so tiny that anyone, even a waif, can stomach you.

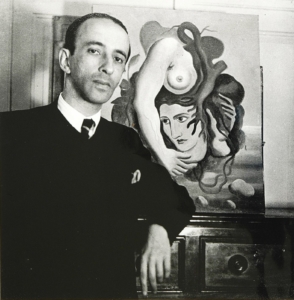

Translator’s Statement

Despite his popularity in Brazil and his immigration to Europe, Murilo Mendes has never found an English translator. His poetry has long been known in France, partly due to Mendes’ friendship with notable figures of the French avant-garde such as André Breton, Francis Picabia, Eugene Ionesco, as well as Nobel laureate, Albert Camus. But in the English-speaking world Murilo Mendes’ poetry is virtually unknown. The five poems translated here appear in English for the very first time.

These five poems were originally published between 1931 and 1941, before Mendes left Brazil. Mendes was at first influenced by modernism, an artistic movement inaugurated by Mário de Andrade in Brazil in 1922 (the centenary of which was just celebrated in São Paulo) but he was more attracted to surrealism, which is evident in these poems. Mendes loved to play with images, and nothing juxtaposes images in a more challenging way than surrealism. The difficulty in translating surrealist poetry is that the original language doesn’t always make sense. Take, for instance, André Breton’s infamous ‘soluble fish’. Neither in French nor English does a soluble fish make much sense, as soluble things tend to dissolve in water which is the very substance fish need to exist, but the image is striking. It forces us to stop and think. And that’s the point of surrealism. In Pré-História Mendes writes of his mother “playing piano in chaos” which doesn’t make much sense if we try and figure out how anyone can do anything in chaos, let alone play the piano. In Estrelas Mendes lists various species of stars such as fish stars and piano stars and blind stars, which will probably have astronomers and astrophysicists scowling in bafflement or annoyance, and A Mulher do Deserto depicts a thirsting woman whose hair and hands are made of palm leaves and thistles. None of this makes much sense, in Portuguese or English, but the images are striking, and that’s the point of surrealism.

It’s been said that a translator must choose between fidelity to the original or beauty in the target language, the “belles infidèles” of Gilles Ménage. In these translations I have sought to render, as faithfully and as beautifully as possible, the striking imagery of Mendes’ poetry so that readers can experience what it’s like to encounter Brazilian surrealism without needing to read Brazilian Portuguese.

Murilo Mendes was born in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais in 1901. In 1930 Mendes published his first collection, Poemas: 1925-1929. Mário de Andrade, the father of Brazilian modernism, celebrated the collection stating it was “historically the most important book of the year.” In the 1950s, Mendes emigrated to Europe meeting surrealists such as André Breton, Franics Picabia, René Magritte et al. Surrealism was, and would remain, a significant feature of Mendes’ mature work. Mendes settled for a time in Rome, teaching Brazilian literature, then retired to Lisbon, where he died in 1975 two years after completing his final collection, Retratos-relâmpago.

Baz Martin Gibbons’ critical essays on film have been published in the Directory of World Cinema and World Film Locations series published by Intellect Ltd. (UK) and University of Chicago Press (USA). His most recent publications include a chapter from his memoir I Sing the Mind Electric (Watershed Review) and translations of Brazilian poet Augusto dos Anjos in POETRY, published by the Poetry Foundation (USA). He currently divides his time between Brazil and England.