Never Enough: The Life and Trials of a Perfectionist

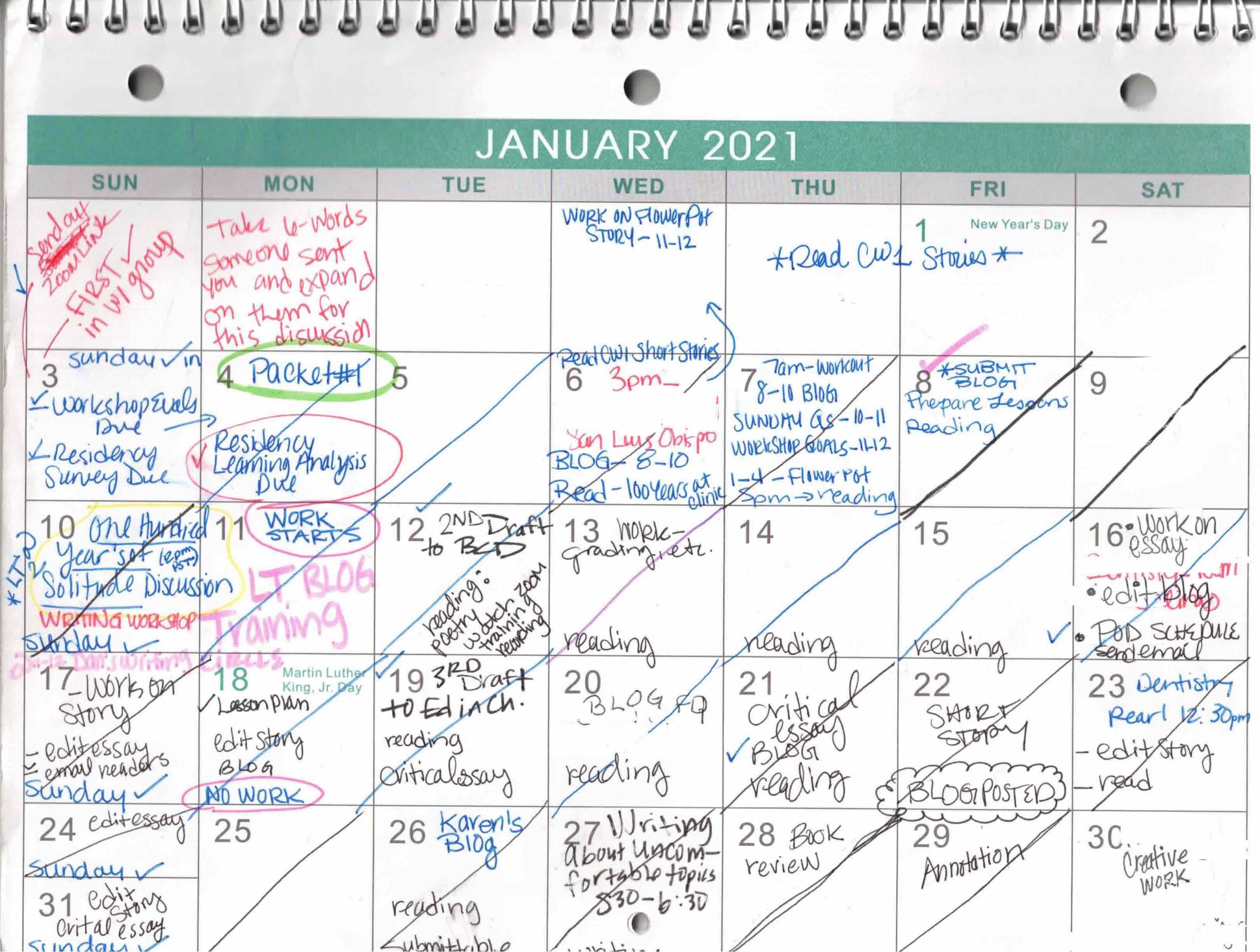

I gave myself a weekend to relax. From Friday night to Sunday morning, I would only spend time with my horses or watch TV. Sixty-hour work weeks had become the norm for the past six months; I needed a complete break. But restlessness quickly set in because I had nothing planned. So, I wrote out a to-do list.

I gave myself “art assignments” to accomplish by the end of the weekend. I grabbed a book, so I could “relax productively.” Fifteen minutes in, I had my Post-Its and was annotating my text. That night, and the two after, I worked on my writing until one in the morning. By the end of the weekend, I felt unrested, agitated, and resentful. And the subsequent weeks went much the same way.

For the past seven years, I’ve worked as an English and Creative Writing teacher. During that time, I’ve had positive performance reviews and been appreciated by my community. My work has earned me an award and a TV interview. I should be proud. Instead, I often feel nervous and restless. I’m indifferent to my accomplishments and itch for the next ones. Achieving one goal just means my subsequent measurement of success is moved further and further away.

What I experience goes beyond merely seeking excellence and having high standards. I compare myself to others and become easily discouraged when I can’t match their success. Individual events and conversations haunt me for days, and I ruminate on what was said, playing out alternate scenarios until I’m so upset, my heart races and my cheeks flush. Relinquishing control is difficult for me, so I will often volunteer to be the first to do a job. Even if I am already stretched thin with time, I will do it just to set the standard. The first blog and book review I wrote for Lunch Ticket are testaments to this. Accepting criticism is also difficult for me, so I avoid situations where I may fail. During my twenties, if I received negative comments on my performance reviews, I would often sulk and self-sabotage, sometimes for weeks. I frequently set unrealistic expectations, then judge myself harshly for not meeting them. The most damaging of it all is I lack self-compassion. When I fail, it’s not because failure is a part of life. It’s because I feel like a failure.

I am a perfectionist.

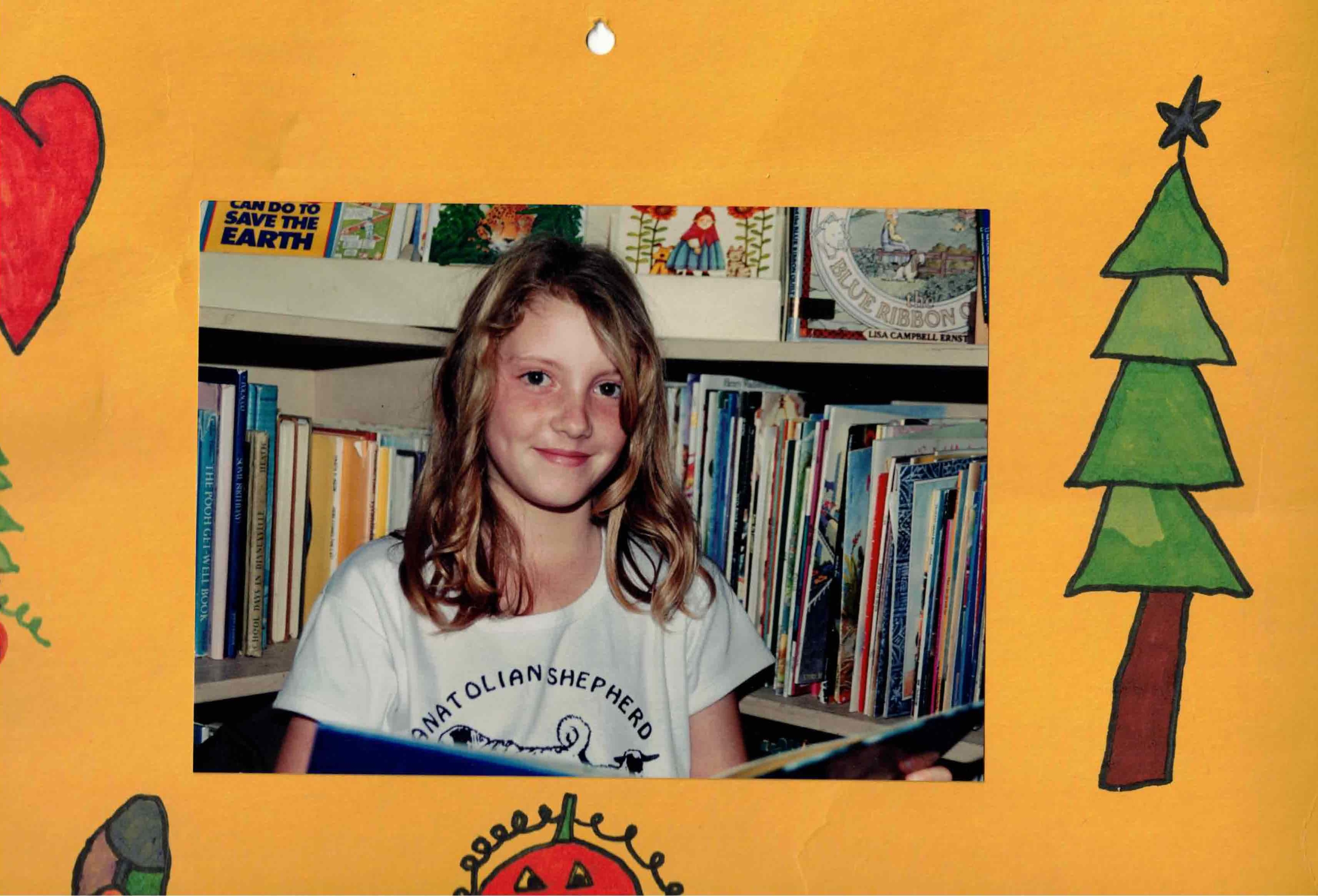

Perfectionism— “the need to be or appear perfect” —is something I’ve struggled with much of my life. As a teen, perfectionism manifested itself in my procrastination streak and self-consciousness; when you expect failure, fear immobilizes you from trying at all. But my anxiety and hyper-critical nature intensified over the years. As a young adult, I had few close friends, no co-workers I trusted, and a chronic need to be acknowledged. At first, I would spend months committed to perfecting my work, wherever I was currently employed. But I always worried about not impressing management and about losing my job. Ultimately, self-sabotaging would get me fired. And I got fired a lot.

When I first applied to grad school, I wasn’t accepted. When I received that rejection, I felt punched out, embarrassed, unworthy. I scrutinized one C+, my resume, my essay. My anxiety intensified until I talked myself out of applying to other schools. Like many perfectionists, I often avoid challenges and opportunities if there’s a chance they could yield disappointment.

Researchers and society have mixed feelings about perfectionism because this trait is often considered by many as necessary and valuable. Social media comparison culture and an increasingly competitive job market could partly explain why perfectionistic tendencies have been on the rise over the past thirty years. Being a perfectionist isn’t always viewed as a negative trait. While maladaptive perfectionists are often crippled by their failures, if you’re an adaptive perfectionist, you may have high standards without feeling the need to be perfect. This seems, then, like a positive quality. But some researchers believe distinguishing between adaptive and maladaptive perfectionists is a step in the wrong direction. And so do I.

While yes, my perfectionism has contributed, at least in part, to the drive of having to do well, I know how dangerous it can be if left unchecked. Perfectionists suffer greater from depression, anxiety, stress, and are at higher risk for having suicidal thoughts. Lacking self-compassion, the perfectionist finds recovering from failure difficult. Paul Hewitt, a clinical psychologist, and professor at the University of British Columbia, says perfectionists try to fix their flaws by being perfect, even though this is an unattainable goal.

Complicating it further, perfectionism can also manifest in different ways: “Self-oriented” perfectionists expect perfection from themselves; “Other-oriented” perfectionists expect it from others; and “socially prescribed” perfectionists need others to value them. I’ve experienced each of these, so I question whether the line between them is hard set (and to be honest, defining them may not help me combat their side effects, anyway).

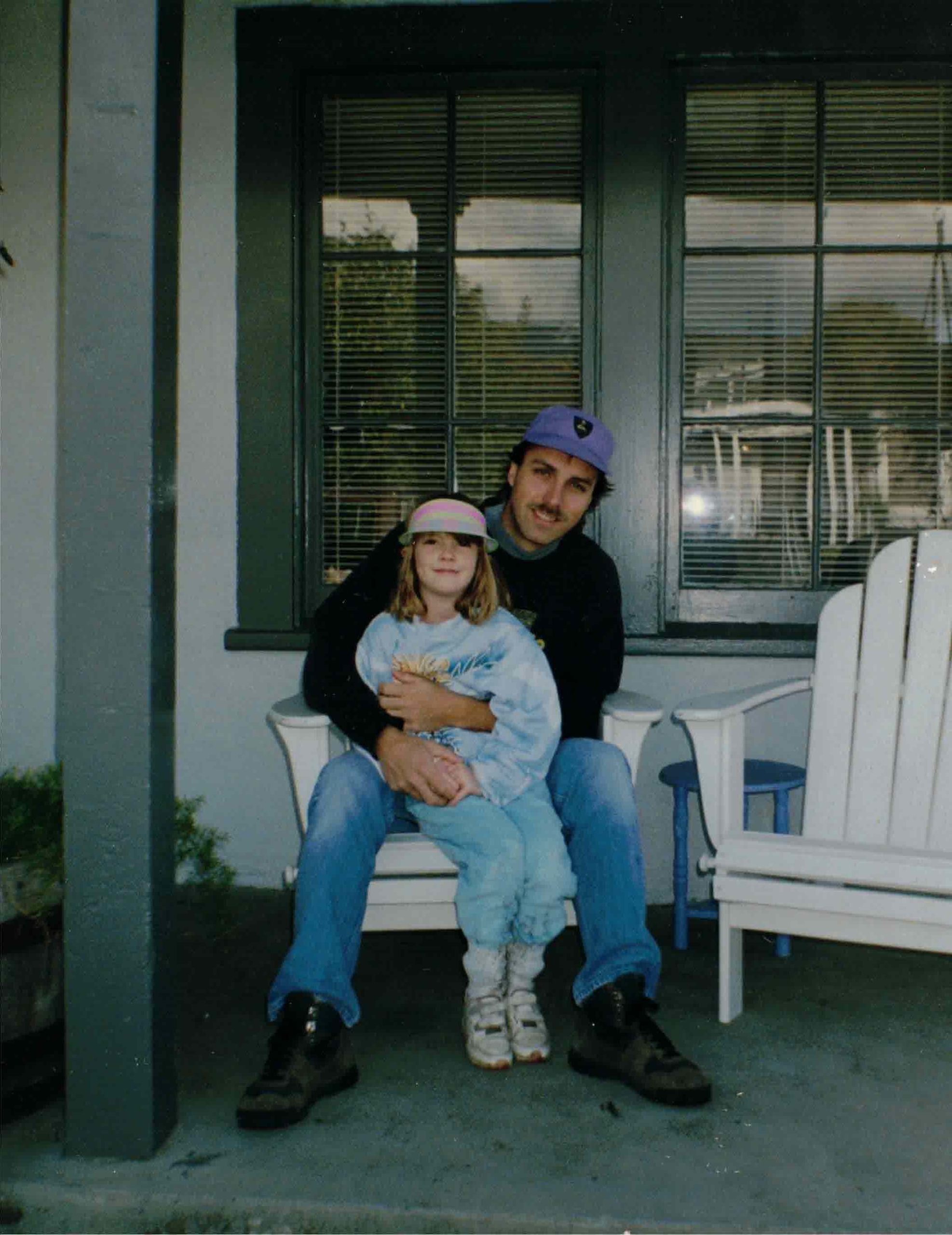

Perfectionism is difficult to eradicate because it usually has roots in “adverse childhood experiences.” For me, this is true. My parents’ separation when I was five and other childhood traumas led me to become a withdrawn and broody teenager.

A turbulent decade followed their separation. We moved around a lot and boarded friends and strangers in our home. I lacked structure and never developed a strong work ethic. But after persistent pleas, and a failed freshmen year, I finally got to live with my father.

Initially, I was elated, albeit apprehensive. When I had visited him on summer vacation, it was only ever us. His partner had always found somewhere else to be when I came to town. So, it was difficult to adjust to living with my father full-time and a woman who was virtually a stranger.

Their home is beautiful—three stories nestled between redwoods with wall-to-ceiling windows and enough rooms for me to have my own bedroom and bathroom—yet I felt uncomfortable and out of place. The house echoed like a cavern and was cold. It sat under the umbrella shade of the redwood trees for all but an hour or two a day, so I spent most of my time wearing wool socks and a sweater. Unlike life at my mother’s house, there weren’t screaming siblings, skipping school days to ride horses, clothes piled like ant hills on couches, or fights followed by hugs. My dad and his girlfriend watched plays and visited museums, shopped at farmer’s markets, and went on holiday in France. She’s a successful business writer and he owns a drywall business. Moving there felt like I had stepped into other people’s lives. I didn’t fit right. Even the paint color I chose for my bedroom—a stormy blue-grey—was unacceptable. (They chose a sunflower yellow instead.) It was a month before I went to the fridge without asking permission. And my discomfort persisted.

First semester grades showed I was failing, again. To remain living with them, I had to sign a 15-page contract agreeing to a study, chore, and cooking schedule (so I could contribute to the household). This contract also established his girlfriend as my permanent tutor. I rebelled. For the next year, the three of us constantly fought about my grades, schedule, and general demeanor.

Toward the end, we co-existed in separate spaces—my dad and I in one, he and she in another. I cried most nights and looked for ways to stay out of the house. I was so angry, and hurt, that I stopped saying goodbye to him when he dropped me off at school. My father and I had always been friends, but in one school year, we had become strangers. The truth is, neither of us knew how to express what we felt. How could I tell him that I thought he was embarrassed of me? And how could he break through the ice that had encapsulated us both?

At the start of my senior year, he got me my own apartment. He explained he wanted to teach me responsibility and how to live independently. I suspected I was not welcome to live with the two of them any longer. I viewed, and in some ways still do, this action as a second abandonment. Though maybe this is unfair.

During my third year of college, I began therapy. Eventually, my father and I spoke, and we let some old hurts go, which helped a little. Sometimes I wonder whether we would have a stronger relationship now, had I not lived with them then. But that’s a what if I try especially hard not to ruminate on. Despite my work done in therapy, I never actually eradicated the roots of my perfectionism. So, my internal demons continued to grow.

***

After I received my teaching credential, I landed a good job and found a supportive partner. On the outside, I appeared put-together, successful, and well established. But inside, I still struggled.

I took on unnecessary responsibilities, ruminated constantly, and lacked self-compassion. I sought validation from others because I hadn’t learned how to value and be proud of myself. I was always worried about disappointing someone. I kept these feelings mostly under wraps, but when I initially applied to grad school and was rejected, I triggered that old trauma of feeling unworthy.

But the mind is pliant and can be rewired. Living under the restrictions of Covid-19 this past year has given me the time to think and reevaluate the direction of my life and work toward change. I applied to an MFA and was accepted. I’m doing well so far and feeling accomplished. I started a writer’s group, so I can make friends. I’ve asked for help with school when I’ve needed it and forgiven myself when I haven’t met deadlines. I’ve also set clear boundaries at work to protect myself from burning out, a constant occurrence in the past. I now try to pace myself and balance my responsibilities. I challenge myself and forgive myself. I try to be my own ally.

I read an interesting article while researching perfectionism. One woman gave her inner perfectionist voice a name. She said it helped her identify when that voice was speaking and to treat it with compassion. In this same spirit, I, too, named my inner perfectionist. When I feel a surge of negativity, I ask her why she wants to be heard. I say her concerns are valid, but instead of getting hurt, I ask her if we can go about things another way. I tell her she’s worthy and loved. I tell her she’s not a failure. I tell her I am proud.

Though my worries are still with me—I still experience aggressive bouts of self-doubt and anxiety, especially in stressful times—I am trying. And though I’m nowhere near the end of my journey, I’m on my way.

Ashley Russ is a current MFA candidate at Antioch University. She received her BFA in Creative Writing from UC Riverside. Her work has appeared in UC Riverside’s Mosaic Art and Literary Journal and in Endurance News. She resides in California where she teaches, rides horses, and is working on her first novel. Twitter: @TheWritingRuss