No Other Loss Can Occur So Quietly

I used to pray a God was listening

I used to make my parents proud

I was the glue that kept my friends together

Now they don’t talk and we don’t go out

I used to know the name of every person I kissed

Now I made this bed and I can’t fall asleep in it.

– Brand New, “Millstone”

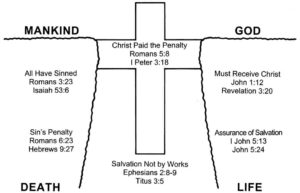

Album artwork from Brand New’s “The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me.”

My younger sister thought I hated her in high school. Every morning I’d drive her to school in my white 1986 Honda Civic, saying absolutely nothing. We’d wind down Crow Hill on Highway 285, past the crumbling granite and pine trees, through the town of Bailey, alongside the South Platte River, till we made it to our school, Platte Canyon High. I was a junior, then a senior. She was a freshman, then a sophomore. The ride would take fifteen to twenty minutes and, according to my sister, I would say absolutely nothing.

I have no memory of this, but my sister swears it true. Knowing the 4.0 GPA / school council member / star volleyball player that she was, I am inclined to believe her. I don’t think I talked to many people in high school. I always seemed to be lost somewhere deep inside my head.

Picture this: Me, a passionate teenager full of faith driving to high school in my white Honda Civic that burned through a quart of oil every other time I filled up for gas. Me, unsure about myself, but ambitious. Me, full of doubts and insecurities, but confident that as soon as I graduate, the world will open itself.

Do you see it? Me, with my idealism and passion listening to Christian-ish hardcore bands like Thrice, Underoath, and Norma Jean? Unsure how to put all this energy to use, I wondered where I could make a difference, confront the injustices and ills of the world, how I could show all those cynical, disillusioned adults that change was possible, how would I make something of myself, fall in love, finish school and start living in the real world.

Picture me in my Civic, disappearing in a cloud of leaking-engine-oil-smoke, as I start my car up. Look at me; look at yourself. Do you remember what it was like to feel like the whole, beautiful world was ahead of you, wide-open and full of possibility? Full of love, poetry, art, but, most importantly, hope that change was possible, even if your situation was not the best?

* * *

In high school I was an intern for our church youth group. I led small groups and helped the youth pastor, Jay, with various administrative duties. I then went to Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado where I was youth pastor for a semester and involved in para-church ministries like Campus Crusade and Young Life. I moved to Denver to help some friends start a church, and then to Portland where I went to a church called Imago Dei and was involved in ministries to the homeless, led a college group, and attended a house church. I moved to Salt Lake City, Utah to start another church because I believed in church. I went to Africa and Haiti on mission trips. I read books on religion and took theology classes. I practiced simple living and participated in community. I protested wars, the detainment of immigrants, and the greed of Wall Street. I got multiple Jesus tattoos. I very nearly went to seminary.

Yet, I was also hibernating in some ether-world. Like my brain was underwater or down some deep pit, where sight and sound took longer to reach. I was somewhat depressed, as I am still today, although then I had no words, no vocabulary for it. My depression worsened over time, from the melancholy of my youth to a full on clinical diagnosis and 40 mg of fluoxetine a day for the last decade. If my sister had spoken to me while we’d been driving to school, it’s likely I wouldn’t have heard her. My head was filled with stuffing. I might have muttered noncommittal responses, but my mind would have been on a distant planet, on a rogue-tangled mission to discover abstract secrets of the universe.

Did my depression worsen as I grew to adulthood because I was losing my faith in the church? Or did depression itself sap the feeling of anything in my life, including my faith, over the years?

Depression does not have a set time-span. While you’re in it you feel totally untethered to anything around you. For some, stabilization comes via meditation, exercise, anti-depressants, therapy, or faith. Music, love, art, or writing provides solace for others. Writing, as a practice of putting things into context, offers the same end as therapy. Writing allows me to examine my personal history, the harmful coping mechanisms I employ, and my hopes of trading them in for more positive ones, perhaps, writing a better story for my future.

At its core though, what writing or therapy or meditation gives is agency. A regain of control. A manipulation of life’s narrative. This feels incredibly potent after living as if I were merely a piece of debris floating in the ocean, flung this way and that, battered by storms, with no real say in the matter. Though depression doesn’t need to have any reason, external factors can exacerbate the condition. The biggest factors that fueled my depression were my struggles with faith, compressed realities of adulthood, and crutches I used to cope with both. Faced with suicides and miscarriages, I shredded my stomach lining with booze, cigarettes, and coffee.

I felt that the Christian God I had built my life around, moved states for, and served devoutly, seemed to slowly vanish when I needed Him the most. I didn’t feel God at all. God for sure as hell didn’t talk to me. I was in a dry desert for a decade with no end in sight. If there was a God, I was pretty sure God hated me. The God of my Fathers had failed me.

* * *

By adulthood, I had spent years teetering on the thin edge between doubt and faith, between belief and non-belief. From high school to college to now, I spent years navigating the tensions of culture and politics, liberalism vs. conservatism, depression vs. feelings, trying to reconcile with my faith. I became a Christian liberal. Then one of those Pharisaical New-Calvinists. Then a Christian anarchist. An anti-war Christian. An anti-consumerist Christian. I found churches that on their surface seemed to be different from what I grew up in, only to realize they were, at the core, the same strain of fundamentalism, merely covered with tattoos and rock music and a slightly more liberal approach to politics. When it came to women in leadership, the LGBTQ community, the blind support of Right Wing Politics, the chokehold of dogmatic “truth,” nothing was different. I felt that even the “fundamentals” from Jesus, such as the Sermon on the Mount or the command to “love one’s enemies,” were grossly overlooked in favor of sin management (particularly with regards to sex), church politics, and individual purity. I watched as close friends left church. But I stuck around. I wanted to believe. I was the Roman Centurion who proclaimed to Jesus, “Lord, I do believe, help my unbelief.” But by my mid-twenties I was a tired Christian.

I wanted to make it work. But the church, that entire world, seemed framed by what contemplative Franciscan Richard Rohr calls “dualistic thinking.” And I could no longer look at things as either/or, as dual. Scripture was too haunting and complex to me. The world was too complex.

* * *

Growing up I often-heard salvation described as a bridge. In the analogy, the bridge stretched from this world into heaven, the substance of which was made by the upper horizontal line of the cross. It was often shown as a diagram. Man walked over the arm of the cross from sin and death to salvation. While perhaps theologically simplistic, the imagery worked for its accessibility. For many years the three were one for me—the world, the bridge, and the hope of salvation (in this case, through Jesus). I existed in a united system of ideas I called Faith. I may not have been across the bridge in heaven yet, but I was on the bridge of salvation. Over time, however, the bridge seemed to disappear, and I found myself looking across a chasm to the other side. The faith that had brought the two ends together vanished. I found myself unable to muster the magic of faith to form the bridge. I could see my friends and family across from me, but I could no longer make the actual journey.

* * *

Kierkegaard

Kierkegaard (the great existentialist of faith) once said: “The greatest hazard of all, losing one’s self, can occur very quietly in the world, as if it were nothing at all. No other loss can occur so quietly; any other loss – an arm, a leg, five dollars, a wife, etc. – is sure to be noticed.”

I was done and yet not done. If I was to keep living, I knew I must find something else to replace my lost faith in the church. Art had complexity; writing had complexity; music had complexity. Engaging in these, I felt the sort of transcendence I had been looking for in religion. What bothered me then was that no one else seemed to appreciate the complexity of all this. Most people seemed happy enough with sermons and T.V. shows and mediocre books. Everyone was either busy or sedated or both. Until I found art, my mind raced as if each second was the last, as if I did not find meaning or truth as soon as possible, I would have to end it all, kill myself. I felt as if I could not last another second in the simplistic black and white type of world. With art, I felt my faith journey transforming into something else. It was like I needed to break myself away from faith in order to one day come back with fresh eyes.

Perhaps more than anything, I miss the young man that I once was. Me, flying down the hill towards the whole, beautiful world. I wonder if I will ever see him again, or if he is lost forever. I wonder if that would be a good or a bad thing. Or if that’s just how it goes. And so I began the delicate, almost impossible, process of reconciling myself with the world.

Levi Rogers is a writer and coffee roaster out of Salt Lake City, UT. He lives with his wife Cat, his dog Amelie, and his many socks, all of which have holes. He’s currently an MFA candidate at Antioch University Los Angeles.