Normal Behavior

I had forgotten how completely ubiquitous sexual harassment was in my youth. So common place on the streets and transport systems in a city like New York that young girls and women took it in their stride, assuming the abuse to be the price paid for a sense of autonomy, for the freedom of movement. But were we free? Are we free in the ways that Americans think of themselves as free? Or were we simply absorbing sexually aggressive behavior as normal.

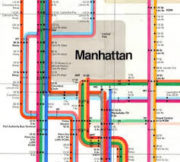

When I could, I stood up for myself in public spaces, often responding with rudeness. I’d shout in a crowded subway car, where an assailant hoped he was being discreetly repugnant—hey, nobody wants to see your dick—my assailant moving along as quickly as possible, leaving nearby commuters to wonder what had just happened. I was lucky. But under certain circumstances, I simply froze. Again I was lucky.

When I could, I stood up for myself in public spaces, often responding with rudeness. I’d shout in a crowded subway car, where an assailant hoped he was being discreetly repugnant—hey, nobody wants to see your dick—my assailant moving along as quickly as possible, leaving nearby commuters to wonder what had just happened. I was lucky. But under certain circumstances, I simply froze. Again I was lucky.

The sense that sexual aggression was or is normal took root early in my psyche. As a child, I witnessed the harassment, cat calls and leers, endured by my mother while she negotiated the streets, her children in tow. We never spoke of it, of how it made her feel, but I believe this is when I began to absorb the idea that power-based shaming behavior was normal.

* * *

In Sherman Alexie’s new memoir You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me, he writes of the prevalence of sexual assault on the Indian Reservation of his childhood. He speaks of generations of degradation, writing that the abused often become the abusers.

I mention Alexie because of the horrific allegation of sexual aggression currently tearing through media, entertainment and politics. I can only imagine the depth of crime perpetrated against the most vulnerable, those who exist within the darkest corners of American society. If elite women in media are not safe in their workplaces and if major Hollywood starlets are not safe, what help is there for the housekeeper, the factory and hospitality worker, the farm laborer or a young woman making her way in public housing?

Here are some of my recollections.

I began music lessons early, moving quickly from recorder to viola between the third and fourth grades. My very first music teacher, Mr. Rosen, was my Maestro. He was dedicated to teaching children. At St. Marks Lutheran Church in Bushwick, I took piano lessons from Mr. Mineri, the organist and choir director. These two men set the standard for teacher student interaction during my childhood. I was safe in their presence and I learned my lessons. Mr. Rosen’s—repetition, repetition, repetition—is an ethos I follow to this day when attempting to master a skill.

As I grew into early adolescence there were other music teachers. A young male college student came to our home during my teens. Tall and studious, I studied piano with him through junior high and into high school. Later, during my freshman year in college one of my professors taught private lessons on the side. I visited his New York apartment. I worked on Chopin Études and Bach Inventions. He, like the others, was a caring nurturing teacher. Because of the examples set by these men I developed certain expectations, and thought nothing of following up on an ad in the Village Voice that read Jazz Piano Lessons with Professional Jazz Pianist.

It was the seventies and I had just started attending Hunter College, part of CUNY, the sprawling City University of New York system. Already in the Hunter madrigal choir, I began singing standards with the college’s jazz ensemble. I knew little of jazz chording and wanted to learn, so I called the teacher. I was nineteen or twenty. Used to dodging trouble on the streets, working in a dress shop on Lexington Avenue and paying for my own piano lessons. I didn’t tell anyone I was going. I had nothing to fear.

The first lesson went well. My new teacher taught me the circle of fifths, a new concept for me. I left excited and practiced all week. During the second lesson however, as we sat side by side on the piano bench, my music teacher’s hands began to move up my thighs and over my body. I froze, the behavior not computing in my nervous system. I stopped playing as my shoulders and back stiffened, as my jaw tightened. My music teacher stopped as well. Perhaps he noticed my shock and confusion. Whatever he noticed it caused him to remove his hands.

I didn’t look at him. I don’t know why I didn’t look at him, why I found myself suddenly mute. I thought I knew what to expect when in the presence of a music teacher and I was taught to be respectful and polite to authority figures. My nervous system tried to make sense of what had just happened. For a few seconds, as my stomach churned I sat, confused. Hadn’t I met his big tabby cat? Didn’t he tell me that he shared this sprawling West Village apartment with his wife who was at work? It was the middle of a work day. And I was in the apartment of my new music teacher.

I closed my music book on the circle of fifths and jazz chording and said—I have to go. I remember holding the music book close to my chest as I grabbed for my bag beside the piano. He said—alright—and stood up. He walked me to the door. I remember looking down. I believe I whispered—thank you. I still could not look at him. Was I feeling shame? This was not some random guy on the street or a boy from my neighborhood. This was an older man. This was my music teacher.

As he opened the door to his apartment, I stepped over the threshold into the hallway. I still could not look at him. Did I say goodbye? Did he? I don’t recall. My music teacher closed the door behind me and I never took another jazz piano lesson.

* * *

In a November interview the feminist writer bell hooks states that the roots of male aggression can be found in their childhood experiences, that the primary form of child abuse is shaming and that she would not be surprised to learn that men like Harvey Weinstein were abused as children.

Hooks reminds us that sexual aggression is so normalized the only real solution is to address its ubiquity within the family structure. She states the problem and its remedy can be found in “how we parent children.”

* * *

During high school my friends and I travelled in packs. And though the underground transit system could be a dangerous place, ripe with opportunities for sexual predation, there was always safety in numbers. It was my college years (the off hours, part time jobs and changeable class schedules) that led to my being on the streets, underground and alone among the crowds with ever increasing frequency. I enjoyed a growing sense of autonomy, comfortable in my status as a free American girl, confident in the knowledge that New York was my city, and that I could come and go as I pleased. This is a privilege women in many parts of the world still lack.

During high school my friends and I travelled in packs. And though the underground transit system could be a dangerous place, ripe with opportunities for sexual predation, there was always safety in numbers. It was my college years (the off hours, part time jobs and changeable class schedules) that led to my being on the streets, underground and alone among the crowds with ever increasing frequency. I enjoyed a growing sense of autonomy, comfortable in my status as a free American girl, confident in the knowledge that New York was my city, and that I could come and go as I pleased. This is a privilege women in many parts of the world still lack.

Unaware of my privileged status I began to cultivate a veneer of toughness: keeping my eyes straight ahead, refusing to acknowledge the presence of a man unless his unwanted attention forced me to. I began to notice where a man kept his hands in relation to his garments, in relation to me.

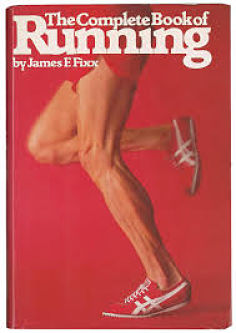

There was a neighborhood man, tall and lanky, who ran, as I did. I knew him, I liked him. We talked sometimes. And sometimes we ran together. But often while on the track he sped up, out running me. When that happened, he slapped my butt each time he passed by. This didn’t happen every day. I didn’t see him every day. But when our schedules aligned he would come up behind me, slap me across my buttocks and keep going. Whenever I asked him to stop he chuckled and said—Hey, I’m a man. It was a clear sense of entitlement to him and it got to a point where if I saw him I learned to run on the street or stop for the day. It made me angry but I felt powerless to change his behavior so I altered my own.

There is something about culturally systemic behavior that we absorb and accept. During the years in which I came of age, phrases like—men are men—and—hey, I’m a man—were commonplace. I suppose they still are.

Once after finishing a run I entered the lobby of the building within the housing project where I lived. I was greeted by a young man dressed as a housing groundskeeper. He announced that due to a smoke condition, the elevator was unavailable and that I should use the stairs. I saw and smelled the smoke so I took the stairs.

Once after finishing a run I entered the lobby of the building within the housing project where I lived. I was greeted by a young man dressed as a housing groundskeeper. He announced that due to a smoke condition, the elevator was unavailable and that I should use the stairs. I saw and smelled the smoke so I took the stairs.

Living on the twelfth floor I used the stairs often. I wasn’t afraid. I lived in the building. At about the sixth floor I heard the door downstairs close. By the time I reached the tenth or eleventh floor the same young man from downstairs was standing behind me. He cornered me, pushed me up against the wall and asked for a kiss. Winded, my reaction was anger and I began to scream bloody murder. He froze. I kept screaming and probably cursing. He, now startled by my reaction, ran off. I ran all the way to my family’s apartment crying.

It was after eight a.m. With my younger sisters in school and my mother at work, there was no one to tell. Showered and changed I walked directly to the Housing Police station in order to report the incident. I remember that I was wearing a skirt, a white tee shirt and sandals. The police officer suggested that we take a ride around the neighborhood in the patrol car to see if we could find the guy. When I reached for the back door of the patrol car the officer said—you can sit up front. So I did. I sat in the passenger seat in the front of the patrol car. Again, I had no reason to fear. He was a cop. Older, friendly. We drove around. We couldn’t find the guy, but at some point, the officer’s hand was on my thigh, squeezing it. Again I froze.

It’s funny, that freeze. It’s the nervous system going wacky. For a few seconds, nothing computes. You think you’re in a safe place, that the person you’re with is there to protect you, not violate you, so the body simply doesn’t know how to handle the information it’s receiving. The physical response, the freeze, is a shock of sorts.

I say I was lucky because each time I was confronted by unwanted attention, I was either able to get away or somehow give off a signal that the attention was unwanted, inappropriate. The aggression I experienced, though opportunistic, was in its way exploratory. It was as if each man was testing the waters, seeing how far he could go. I was lucky.

I’ve never been raped, but I know women who have and I can only imagine how the quiet shame of being so violated must last a lifetime. But the persistent, omnipresent occurrence of the uninvited touch, boundary crossing leer and crude remark… that I know about. I know what it’s like, to live with frequent sexual harassment. Most American women know. It is normal behavior. YES it is.

The police officer, clocking my reaction, said nothing. He simply pulled over and stopped the patrol car. I got out. He drove off and the original assailant was never seen again. I never reported the cop. I never mentioned the incident. I had learned to shrug it off as normal.

* * *

No longer that woman who gets hit on in the street, I think about the prevalence of the harassment I withstood and how it affected my younger self. It made me cautious, my inner antennae always active. Though the actual physical and verbal assaults have receded into the past, it is because of recent events that I have begun to recall my own experiences—the lewd comments, frisky hands, and exposed penises in crowded subway cars meant for my eyes only. The behavior inspired different emotions in me, sometimes fear, sometimes shame, sometimes anger and defiance.

In the wake of Harvey Weinstein and subsequent revelations, and with an admitted sexual predator in the White House, I can’t help but be reminded of my own past experiences and I know in my gut that this behavior is accepted as normal.

Some men feel entitled to comment and leer, grope or worse. Other men’s daughters, wives, sisters and mothers are fair game because running through our culture is an unspoken view that women are on the planet to serve the needs of men, for the pleasure of men. The behavior this view encourages, ranging from unwanted verbal attention to violent assault, is omnipresent.

Some men feel entitled to comment and leer, grope or worse. Other men’s daughters, wives, sisters and mothers are fair game because running through our culture is an unspoken view that women are on the planet to serve the needs of men, for the pleasure of men. The behavior this view encourages, ranging from unwanted verbal attention to violent assault, is omnipresent.

Perhaps the only respite is aging out. Donning that “cloak of invisibility” earned with advancing birthdays as suggested by Katelyn Keating in her essay Not Fade Away. However, I believe sexual harassment—like racism—is about power, a power dynamic that is learned while young, a learned phenomenon that can also be unlearned. It’s time to change the culture.

* * *

A favorite activity during my high school and college years was attending the New York Auto Show. It was fun for the young bridge and tunnel crowd, sitting behind the wheels of cars we would never own but dreaming our big dreams all the same. Promotional giveaways were common—buttons, caps, mugs etc. This time there was a large vat filled with rolled posters of some luxury product I currently can’t recall. I remember converging on that vat with my friends, reaching one arm into the large container and grabbing a poster for myself while feeling a hand squeeze my rear end. I didn’t freeze. This time I kept my wits about me. But I didn’t turn around. While the unknown person enjoyed himself (I assume it was a he), I took my free hand and placed it on top of his and before he could pull it away I dug my thumb nail into the top of the hand while holding on as long as I could. As my unknown assailant struggled to pull free, I dug that thumb nail into his hand as hard as I could. Finally, he broke free. I didn’t turn around. I have no idea who my assailant was. But I have never forgotten the feeling of satisfaction.

Angela Bullock is an actor/writer with an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Antioch University LA. She has been published in Annotation Nation and Lunch Ticket.

Angela Bullock is an actor/writer with an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Antioch University LA. She has been published in Annotation Nation and Lunch Ticket.