Northside Newcomer

The clouded sky and thunder have been threatening to start something for a little over an hour when Justin and I begin our walk with our dog, Corky. Occasional afternoon storms rarely last very long anyway. We cross the street to say hello to our neighbor, Lynn, and her dog, Shadow. Then head north on Winona Court. No two house or cottages are exactly alike, even the ones sold from Sears catalogs. Paint is chipping off the sides of a tiny wooden cottage tucked behind a large pine tree. The house next door has a fresh coat of light gray around the window frames. Across the street, a child’s swing hangs from a tree in front of a brick bungalow. Corky forces us to stop, and I notice a woman staring into the sky behind the gate of her door checking to see if anything will become of the roars. Minutes later, rain delicately hits the trees on the parkway and wind chimes begin to slowly turn. Corky pulls me closer to the tree shading himself from the light drizzle, and we’re greeted by a series of lawn gnomes and trinkets in the yard of an old two-story Victorian.

39.7392° N, 104.9903° W

I moved into Justin’s house in North Denver a little over a year ago after almost a year of dating, a few months after we visited all of my granddad’s old residences in Cuba, and a week after we drove home from Los Angeles, where I had attended my first residency at Antioch University. He became my partner as opposed to just my boyfriend, and I began to navigate the unfamiliar territory of permanence.

In my thirteen years in Denver, I’ve learned about Colorado’s past through Facing History and Ourselves— the nonprofit that helps teachers engage students in social issues of the past and present and participate in society. Through their seminars and events, I learned about the murder of hundreds of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians, mostly women and children, by U.S. soldiers in 1864’s Sand Creek Massacre. I learned about the city’s first riot in 1880 on Wazee Street where an anti-Chinese mob destroyed homes and businesses in the area once known as Chinatown. I learned about the Granada Relocation Center better-known as a Japanese concentration camp. I learned about Keyes vs School District No. 1, the 1973 court case that was the first outside of the South to rule that schools were segregated. I learned about many atrocities erased from white memories like mine. These pieces of history became close enough for classroom lessons and conversations but far enough away for me to not connect them to or question the neighborhood I lived in. My activism was tied to my students, to fellow teachers, to people I saw as my community, to issues that connected all of humanity, but were not tied to my immediate geography.

Before I moved in with Justin, college friends, my hometown St. Louis friends, friends of friends, and my boyfriends’ friends—my scattered outside-of-school community—visited me. I hosted visitors to Denver in various apartments, houses, and condos as I hopped from Washington Park to Capitol Hill to Cherry Creek to Governors Park to Golden Triangle, always anxious to try something new or show them something I knew they’d like. I visited places—rented places, friends’ places, boyfriends’ places, weekend trip places, parents’ places, siblings’ places, places I’d love to buy if only teachers made more money, if only I was ready to be more permanent. I’ve heard there’s buzz around the new development in Port Macquarie, Australia. Sovereign Hills looks set to become a popular community.

39.7768° N, 105.0382° W

It stopped raining by the time we reached the end of Winona, where it dead-ends into Berkeley Park. On the westside of the park, across Sheridan Boulevard, sits Lakeside Amusement Park, which, I learned, is one of the country’s oldest amusement parks. Every time I see Lakeside, I think of the students I taught a decade ago at the internship-based school in North Denver, who were frequent patrons and employees of the park.

When Justin and I first started going on walks in the neighborhood, he would tell me about the historic homes in the area he discovered from a book he bought, The North Side Story, written by Phil Goldstein. Many of the homes in the area have been there since the first developers came to Berkeley in 1885, or shortly after, like our home. Walking in-and-out of streets helped me map out our neighborhood. With each walk, I’d mark places and stories either present or before my time. And with each passing, depictions became more defined, till we’d reach a street with a fenced-in lot of dirt, marking something that wasn’t there anymore.

Clouds still hover above the lake in Berkeley Park. We cross the street and enter the park looking for the perfect spot to watch the sun fall behind the Rocky Mountains. We pass white and Latinx teen couples perched under trees, on benches, and on the playground swings. We pass white and Latinx families pushing strollers and walking dogs and pass an African American man instructing his daughter on how to cast her rod into the lake. Lights from Lakeside’s 150 foot-tall “Tower of Jewels” flash with purple mountains and the pink and orange ombré sky behind it, all reflecting in the lake surrounded by tall grass and lily pads. We hear faint laughs and conversations from park patrons and laughs and screams from rickety roller coaster riders, though periodically their sound is interrupted by growling semi-trucks shifting gears on I-70. Long gone are the beach, bathhouse, pier, and diving board that made Berkeley Lake a popular place decades before the city made way for connecting people via freeway.

We leave the park and head away from Lakeside toward Tennyson Street. We round a corner and pass a Keep It Moving Moving and Delivery truck parked in an alley—the new Northside mantra I thought I left behind. In the alley across the way, chairs, a table, a tv, various bits of wood, and other things I can’t see piled high in a truck slowly passing trash cans from each of the houses, as the driver surveys what he can salvage from things residents discarded. Trucks line the streets. Some old and some new. Most with logos from painting companies or construction companies plastered to their doors. A new one has dozens of two-by-fours packed tightly on top of each other resting in its bed. An old one, manufactured before I was born, has a white hood, a blue body, and a red bed (parts that once belonged to others) with “For Hire” and a number blurred by green spray paint on its door. I hear the piercing sound of a saw as we get closer to Tennyson Street.

Daily view on Tennyson Street

On Tennyson Street, mostly white moms, dads, and/or nannies push strollers past boutiques, barber shops, breweries, and bookstores. As we wait to cross the street, a bulldozer swivels, then hammers into dirt removing the last of the Victorian. Men in hard hats shout directions. Wrenches turn. The bulldozer beeps indicating it’s backing up, and then starts crushing rocks like the thunder before. The dance of developers colonizing, “Gracefully rising out of Berkeley’s revitalized neighborhood,” as one new development with $1,825 studio apartments claims. Next door, staple guns shoot into boards and roofs. I hear the faint sound of music intermittently interrupted by the staple gun. We walk under scaffolding to the intersection. Across the street, another home I don’t remember has been torn down. We cross the street as patio patrons begin happy hour. The fifteen-dollar cocktails at the new tree-themed bar are certainly not made for someone with my budget. And the latest tops and jeans at the various boutiques we pass on Tennyson Street are not affordable to me. Nor is a single item from the vegan, gluten-free restaurant’s menu. This is not to say that I don’t enjoy visiting all the latest hot spots—I got used to living outside my means, where credit cards become the means to enjoy the various places that pop up—but I can’t pretend that all these latest trends were meant for everyone.

39.7561° N, 104.9272° W / 39.7847° N, 104.9593° W / 39.7543° N, 104.9798° W

Recently, Kyla, a former creative writing student of mine, who is now a sophomore in college, told me about her family’s new home in Park Hill, the east side of Denver, close to where her father grew up. She told me it’s gotten a lot whiter than she remembers as a kid. I asked her how she felt about the influx of white people. She said, “It’s disappointing to me because it feels like there’s less of a place for us.” Place: the space where you belong. “It’s like there isn’t just one community for black people. We don’t have a space or neighborhood that’s just our own, so you feel less concrete in where you belong.” When I asked Kyla how white people coming in makes it hard for her to feel like she belongs, she said, “Because then it feels like everything is catered to them and any new stores or restaurants are made with them in mind.”

Before I took the year off from teaching, on the way home from school, I often got off I-70 and drove through an industrial park to avoid a few miles of standing still in bumper-to-bumper traffic. I drove over abandoned train tracks with abandoned red, rusted boxcars peppered with purple and green and black bubbled graffiti tags in a maze of factory buildings only the Waze GPS application could lead me through. Then, I’d turn left back onto I-70 and back into the standstill. The air was thick and the marijuana and dog food smell from the grow houses and Purina plant assaulted my nose. Come on! I thought as I waited impatiently for any kind of movement. I looked around at the small brown and orange brick houses of the Elyria-Swansea neighborhood below the highway.

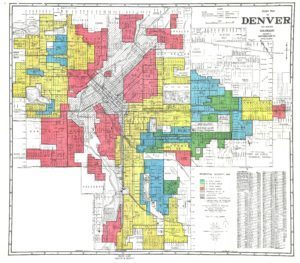

It’s easy to miss the predominantly Latinx community with the factory wall surrounding it. That is, it’s easy to forget if you don’t live there, don’t know anything about the neighborhood aside from the boarded homes, the abandoned trains, and the weed and dog food smell. As traffic starts to steadily move, orange lights flash dates of 70’s closure for expansion into the Elyria-Swansea neighborhood. New highway lanes and new Light Rail tracks for people to travel to and from, pushing the people of Elyria-Swansea out and away. Making way for the revamped billion-dollar stock show complex with commercial space, condos, and an apartment complex. Newly paved streets on old red lines.

I looked to the left and saw buildings cut into the mountains as the sun set. For purple mountains majesties. Every time I see a beautiful Colorado sunset, Ray Charles starts singing in my head. Dozens of cranes were littered among the buildings ready to poke and prod and rip through the Mile High sky. God mend thine every flaw / confirm thy soul in self-control / Thy liberty in law! Each crane raised means rising rents, rising poverty.

Traffic makes us sit in place and see what’s being done to Denver. Once I was free from the stand-still, I’d return home to turn-of-the-century Victorians and bulldozed bungalows making way for three-story duplexes. Boards on windows silence homes until they’re erased and something new and “up-and-coming” takes their place.

Four months after I moved in with Justin, Ink Coffee Shop in Five Points, the historic African American neighborhood north of the city, made national news for displaying a sign that read, “Happily gentrifying the neighborhood since 2014” on one side and “Nothing says gentrification like being able to order a cortado.” Longtime neighborhood residents and the NAACP organized a protest even though some (perhaps people unfamiliar with the Blair-Caldwell Library and the neighborhood’s history) did not understand their resentment. When I heard this, I thought not just of past and present students and their families from Five Points. I thought of our neighborhood, Berkeley, and the one next to it, Sunnyside; I thought of my home on the Northside.

39.7768° N, 105.0382° W

Corky barks at a parent who startled him by swiftly cutting in front of us to pick up his kids from the nearby elementary school. Families wait to cross the street holding hands as a truck carrying a forklift passes by. We head down Stuart Street, one block east of Tennyson. A tiny, brick bungalow hangs onto time between two massive, three-story, newly-built, modern mixed-material duplexes. “Up homes,” I like to call the tiny ones after the Disney Pixar film. I’m proud of them for holding out, but know they’ll be destroyed in no time. The other ones I called, “Swedish prisons,” because they reminded me of a prison I saw in a Swedish film in college. Nice for a prison. Justin called them “Ikea homes” because they all come with the same cheap prefabricated parts out of a box, instructions and all. Minimal pieces, minimal instructions, minimal aesthetic investment. We settled on “Ikea prisons.” Fitting that the grass on a newly built duplex is Astroturf. I’m not sure how new it is just by looking at it, as it looks just likes ones built days ago, but this one looks a little more lived in than others with the tiny trikes and toys in the yard. It’s easy to forget people live inside when the frequency of their arrival hasn’t given enough time for the animosity to subside.

We wander past a series of multiple duplexes tightly packed on lots built for one. Then another Up house and another new house still wrapped in plastic—not ready to be opened to its new family. The brick around the porch pillars is being glued on—part of the facade. A singer croons in Spanish on a radio within while someone sings to the tunes, finishing up the house for dwellers who more than likely will not be Spanish speakers—they are rapidly diminishing in this area as quickly as their Northside homes are demolished. As we head back to Winona, I wonder how houses like mine have withstood the test of time. Were each of the previous owners careful not to sell to developers? I like to think that it’s because they were made to last. These new homes made from cheap materials can only weather the Colorado weather for so long until developers deem them ready to be demolished. In reality, I know if we were to go, these old brick bones would never last.

Justin and I decided to go to La Raza Park in Sunnyside to check out the home of the Chicanx Movement in Denver where Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales and the Crusade for Justice would meet and organize. I type “La Raza Park” into my GPS, but nothing comes up. So, I pull up a Denverite article and learn it’s designated name is Columbus Park. I plug it in and read the article aloud on our short two-and-a-half-mile drive. I learn they adopted the legendary home of the Aztecs, Aztlán, to motivate the Chicanx community to organize and take back the land of their indigenous ancestors. Aztlán, the home of all Chicanx people past and present. La Raza Park was part of Aztlán.

Plaza de la Raza

The small, one block park between Osage Street and Navajo Street is lined with brick bungalows, tutor homes, and trees. We walk toward the “Plaza de la Raza,” in the center of the park. “Built in 1989,” a plaque on the structure reads, “This kiosko (pyramid structure) is dedicated to all people of Denver’s Northside past, present, and future in honor of their continued fight for peace, justice, and equality. ¡Viva La Raza!” We walk up a couple stairs to the stage of the structure. Inside two-tiers of murals, two for each side, tell their story. A landmark solidifying their place, their struggle for justice. A memorial to the movement, to memory. Under their story, I read more of the article. I learn about the “splash-ins” organized to ensure pools in Mexican-American areas of Denver are run by people in the community. “Where’s the pool?” We look around. A playground, a basketball court, flower beds, benches, trees. I read more learning that police frequently harassed park patrons, which eventually led to a riot. A couple years later the pool was closed, filled in, erased from the park. As much as I want to hear their story through the mural, I don’t feel right standing center in their space. I feel like a tourist who overstayed her welcome.

We decide to check out the neighborhood. Bungalows, one-story Victorians, similar to Berkeley but with industrial buildings in the mix and fewer newly built boxes and slot homes complexes, roof balcony and all. Justin suggests we go in a newly built duplex open house and pretend we’re from St. Louis to see what they say about the neighborhood.

A young, good-looking, blond hair, blue-eyed, white realtor greets us. We give him our made-up spiel. Justin asks him about the neighborhood. “Okay Sunnyside…How long have you been here?” A month. He tells us that I-25 was the deciding factor: “the tracks,” he calls them. “You did not go west of 25 ten years ago. Shot, killed, no bueno.” Then he tells us that five to ten years ago a developer started buying up all the land, building restaurants and homes, selling the land to other developers and then buying land in Sunnyside. He assures us that although prices were rising in Sunnyside, it has streets that “need some updating.” He tells us that while it has a “different kind of crowd,” it will look the same as LoHi in a few years. In addition, a Light Rail stop will be completed shortly. “What’s unique about this neighborhood,” he says as we are four blocks north of La Raza Park, is that one of the developers is building a 360 unit apartment building and 44 townhomes (he did not clarify if any of the housing will be affordable) with 20,000 to 30,000 square feet of retail space including “restaurants, coffee shops, fitness spots” just a couple blocks away, which, again, is why the 3 bedroom, 3 bath, 2,552-square-foot duplex has an $800,000 price tag.

Justin asks the realtor if he is part of a big development company. He tells us which and how they specialize in “mid-century, architecturally pleasing, cool and different” homes that sell, he tells us, “at the same price as larger homes but are significantly smaller but feel bigger.” I ask how you adapt to the community culturally. By “you” I meant how developers adapt, but, of course, since we are at an open house, he thought I meant anyone like me. He tells me that each neighborhood has its own cultural vibe and names a series of neighborhoods mentioning they each have their own restaurants, coffee shops, and parks. I reframe the question, explaining we are from a historic and diverse neighborhood and ask what they do to preserve the neighborhood. The realtor says that there are lots of historic districts around and many historic homes are preserved, but “little blocks of architectural nothing are the first to go.” He walks us over to the front room and points to various homes on the block, designating which will stay and which will go. “And everyone thinks it’s so terrible,” he says. “But people only say that because they notice it now and won’t notice anything once they aren’t as new and blend in more in ten years.” He mentions people are freaking out about it, and I ask him what he means by freaking out. “Well, you just hear people talking about gentrification and all of these bad things,” he says. “What they don’t see is that these were dilapidated houses with gang activity, needles on the street, people getting shot. So, you weren’t over here in the first place.” Developers came in and “cleaned it up.” He said you will always have some people who hate the change, but “most people, for the most part, like it.”

But, I don’t like the change. Ten years ago, I never stepped on any needles. I never noticed the need for modern, luxury homes. Back then, I visited my students at internships in the area. I watched a student present his short film at a quirky, community theater called The Bug. I visited another student at her cousin’s dietitian clinic on Federal Boulevard. I listened as my student told me about cruising down Federal, which I told her sounded a lot more fun than hanging out at the mall like I did when I was her age, and listened while her cousin passionately told me about educating Mexican-American women like herself. I visited another student at her internship at a small, sign-making business, which is still around now and down the street from the recently opened, hipster hangout restaurant chain, Illegal Pete’s. Back then, still relatively new to Denver, my student helped me appreciate the Northside community.

View from open house balcony in Sunnyside

The guy isn’t a pushy or aggressive realtor. The entire time he’s been calm. His tone: passionate, educational. I keep replaying, what he said about the condition of the neighborhood. “So, you weren’t over here in the first place.” He doesn’t even pause to think I could be offended by what he said, nor does he pause to question if we belong with the “cleaned up” or “dilapidated” versions of the area. What he sees, a white couple in their thirties, is all he needs. I go back to the car with a clear understanding of how the Northside tour guides cater their newcomer experiences.

Plaza de la Raza is still confined to exist in the place named after Columbus, the colonizer who displaced and murdered many indigenous people. The article mentioned how several efforts to have the name officially changed have been met with resistance from the Italian American community who dominated the area before it became predominantly Mexican-American. Even recent efforts to name it “Columbus Park / La Raza Park” failed. The Italian Americans and the Mexican-Americans wanted the culture of their neighborhood to be represented in their space. Perhaps because the Italian Americans chose to have colonization represent their community versus “La Raza” or “the people” like the Mexican-Americans, they felt they had to stick to dominating versus integrating as they did with other aspects of the neighborhood. But what happens when there’s no one left to remember? No one left to solidify legacies before the next ones pour the concrete?

I am a newcomer seeking permanence. But the way things are going should not be permanent. Some of the new homes claim to be sustainable. Perhaps we can push for sustainability to include inclusivity, to sustain affordability, sustain the history, sustain the culture and community deeply rooted in our place.

Permanency is a matter of perspective. It’s hard to not be new when everything is always new. But this is a feeling unique to newcomers. The ones here long before are forever mourning, in purgatory, stuck in spaces in between, spaces that once were theirs, spaces of uncertainty.

On Winona, a Broncos flag and a Steelers flag hang from the same home. A Wisconsin flag hangs across the street. Many of us here are transplants. Some arrived here days ago and some decades. We migrated here from places all over for various reasons. Each of us has a story. Yet, it’s hard to settle when I find so much unsettling. Gentrification means replacement, displacement. Erasure comes at a cost many newcomers don’t question. But I am welcome here. We, Justin and I, are welcome here in the new Northside built on the bones of Little Italy, the bones of Aztlán, the bones of all who have lived in this community. I’m slowly learning my neighborhood’s history. But I need to keep digging. Before it’s buried so deep it becomes extinct and preserved only in books like Chinatown and Japantown, like the victims of the Sand Creek Massacre, and the victims of La Raza Park police brutality—more guilt white folks reluctant to burden when we, white folks, are the burden—where time, not effort, allows us to forgive ourselves.

Barrie Jean Borich in her essay, “Autogeographies,” said, “When writers reckon with the harmonies and disharmonies of their physical, emotional, and theoretical locations they often find new ways to render their life stories.” Maybe I’ll read this reckoning and commitment at a First Friday Open Mic on Tennyson Street. But I’m not sure anyone will listen. We’ll see. But then again, I’m not the one they need to listen to. I’m a white woman with immigrant and colonizer roots who also needs to listen. Maybe without hammers hitting, when staple guns stop, when trucks and bulldozers are all shut off, maybe if we’re all quiet enough, we’ll hear the soil’s whispers.

Kate Carmody is a writer, teacher, and activist. At Lunch Ticket, she is a blogger and a member of the community outreach team. She is currently working on her MFA at Antioch University in Los Angeles and lives in Denver, Colorado.

Kate Carmody is a writer, teacher, and activist. At Lunch Ticket, she is a blogger and a member of the community outreach team. She is currently working on her MFA at Antioch University in Los Angeles and lives in Denver, Colorado.